(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

Not all boreholes are the same. Scientists of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) used mobile measurement equipment to analyze gaseous compounds emitted by the extraction of oil and natural gas in the USA. For the first time, organic pollutants emitted during a fracking process were measured at a high temporal resolution. The highest values measured exceeded typical mean values in urban air by a factor of one thousand, as was reported in ACP journal.

(DOI 10.5194/acp-14-10977-2014)

Emission of trace gases by oil and gas fields was studied by the KIT researchers in the USA (Utah and Colorado) together with US institutes. Background concentrations and the waste gas plumes of single extraction plants and fracking facilities were analyzed. The air quality measurements of several weeks duration took place under the "Uintah Basin Winter Ozone Study" coordinated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The KIT measurements focused on health-damaging aromatic hydrocarbons in air, such as carcinogenic benzene. Maximum concentrations were determined in the waste gas plumes of boreholes. Some extraction plants emitted up to about a hundred times more benzene than others. The highest values of some milligrams of benzene per cubic meter air were measured downstream of an open fracking facility, where returning drilling fluid is stored in open tanks and basins. Much better results were reached by oil and gas extraction plants and plants with closed production processes. In Germany, benzene concentration at the workplace is subject to strict limits: The Federal Emission Control Ordinance gives an annual benzene limit of five micrograms per cubic meter for the protection of human health, which is smaller than the values now measured at the open fracking facility in the US by a factor of about one thousand. The researchers published the results measured in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics ACP.

"Characteristic emissions of trace gases are encountered everywhere. These are symptomatic of gas and gas extraction. But the values measured for different technologies differ considerably," Felix Geiger of the Institute of Meteorology and Climate Research (IMK) of KIT explains. He is one of the first authors of the study. By means of closed collection tanks and so-called vapor capture systems, for instance, the gases released during operation can be collected and reduced significantly.

"The gas fields in the sparsely populated areas of North America are a good showcase for estimating the range of impacts of different extraction and fracking technologies," explains Professor Johannes Orphal, Head of IMK. "In the densely populated Germany, framework conditions are much stricter and much more attention is paid to reducing and monitoring emissions."

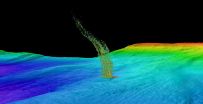

Fracking is increasingly discussed as a technology to extract fossil resources from unconventional deposits. Hydraulic breaking of suitable shale stone layers opens up the fossil fuels stored there and makes them accessible for economically efficient use. For this purpose, boreholes are drilled into these rock formations. Then, they are subjected to high pressure using large amounts of water and auxiliary materials, such as sand, cement, and chemicals. The oil or gas can flow to the surface through the opened microstructures in the rock. Typically, the return flow of the aqueous fracking liquid with the dissolved oil and gas constituents to the surface lasts several days until the production phase proper of purer oil or natural gas. This return flow is collected and then reused until it finally has to be disposed of. Air pollution mainly depends on the treatment of this return flow at the extraction plant. In this respect, currently practiced fracking technologies differ considerably. For the first time now, the resulting local atmospheric emissions were studied at a high temporary resolution. Based on the results, emissions can be assigned directly to the different plant sections of an extraction plant. For measurement, the newly developed, compact, and highly sensitive instrument, a so-called proton transfer reaction mass spectrometer (PTR-MS), of KIT was installed on board of a minivan and driven closer to the different extraction points, the distances being a few tens of meters. In this way, the waste gas plumes of individual extraction sources and fracking processes were studied in detail.

INFORMATION:

Warneke, C., Geiger, F., Edwards, P. M., Dube, W., Pétron, G., Kofler, J., Zahn, A., Brown, S. S., Graus, M., Gilman, J. B., Lerner, B. M., Peischl, J., Ryerson, T. B., de Gouw, J. A., and Roberts, J. M.: Volatile organic compound emissions from the oil and natural gas industry in the Uintah Basin, Utah: oil and gas well pad emissions compared to ambient air composition, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 10977-10988, doi:10.5194/acp-14-10977-2014, 2014.

The Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) is a public corporation according to the legislation of the state of Baden-Württemberg. It fulfills the mission of a university and the mission of a national research center of the Helmholtz Association. Research activities focus on energy, the natural and built environment as well as on society and technology and cover the whole range extending from fundamental aspects to application. With about 9400 employees, including more than 6000 staff members in the science and education sector, and 24,500 students, KIT is one of the biggest research and education institutions in Europe. Work of KIT is based on the knowledge triangle of research, teaching, and innovation.

This press release is available on the internet at http://www.kit.edu.

TORONTO - Dec. 9, 2014 (Toronto) - Scientists at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) have identified a novel drug target that could lead to the development of better antipsychotic medications.

Dr. Fang Liu, Senior Scientist in CAMH's Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute and Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, and her team published their results online in the journal Neuron.

Current treatment for patients with schizophrenia involves taking medications that block or interfere with the action of the neurotransmitter ...

Hummingbirds rely on their ability to hover in order to feed off the nectar of flowers.

It's an incredible feat of flying requiring mind boggling visual processing power, but two University of British Columbia researchers found a glitch in the system, something the tiny birds are powerless to control.

The researchers put hovering hummingbirds through a virtual reality experiment that showed the birds can't control their inflight response to some visual stimuli.

In a laboratory flight arena, hummingbirds hovered around a plastic feeder while images were projected on ...

As solar panels become less expensive and capable of generating more power, solar energy is becoming a more commercially viable alternative source of electricity. However, the photovoltaic cells now used to turn sunlight into electricity can only absorb and use a small fraction of that light, and that means a significant amount of solar energy goes untapped.

A new technology created by researchers from Caltech, and described in a paper published online in the October 30 issue of Science Express, represents a first step toward harnessing that lost energy.

Sunlight is ...

An international team of scientists has discovered the earliest known engravings from human ancestors on a 400,000 year-old fossilised shell from Java.

The discovery is the earliest known example of ancient humans deliberately creating pattern.

"It rewrites human history," said Dr Stephen Munro from School of Archaeology and Anthropology at The Australian National University (ANU).

"This is the first time we have found evidence for Homo erectus behaving this way," he said.

The newly discovered engravings resemble the previously oldest-known engravings, which are ...

Animals that regulate their body temperature through the external environment may be resilient to some climate change but not keep pace with rapid change leading to potentially disastrous outcomes for biodiversity.

A study by the University of Sydney and University of Queensland showed many animals can modify the function of their cells and organs to compensate for changes in the climate and have done so in the past, but the researchers warn that the current rate of climate change will outpace animals' capacity for compensation (or acclimation).

The research has just ...

SAN ANTONIO -- Use of anthracycline-based chemotherapy, a common treatment for breast cancer, has negligible cardiac toxicity in women whose tumors have BRCA1/2 mutations -- despite preclinical evidence that such treatment can damage the heart.

The findings, to be presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), represent a unique effort between cardiologists and oncologists at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center and MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute in Washington to answer a vital clinical question.

"Our study was prompted by evidence from ...

SALT LAKE CITY, Utah, Dec. 9, 2014 - Myriad Genetics, Inc. (NASDAQ: MYGN) today announced results from a new study that demonstrated the ability of the myRisk™ Hereditary Cancer test to detect 105 percent more mutations in cancer causing genes than conventional BRCA testing alone. The Company also presented two key studies in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) that show the myChoice™ HRD test accurately predicted response to platinum-based therapy in patients with early-stage TNBC and that the BRACAnalysis® molecular diagnostic test significantly predicted ...

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- It's widely known that the Earth's average temperature has been rising. But research by an Indiana University geographer and colleagues finds that spatial patterns of extreme temperature anomalies -- readings well above or below the mean -- are warming even faster than the overall average.

And trends in extreme heat and cold are important, said Scott M. Robeson, professor of geography in the College of Arts and Sciences at IU Bloomington. They have an outsized impact on water supplies, agricultural productivity and other factors related to human health ...

Off the West Coast of the United States, methane gas is trapped in frozen layers below the seafloor. New research from the University of Washington shows that water at intermediate depths is warming enough to cause these carbon deposits to melt, releasing methane into the sediments and surrounding water.

Researchers found that water off the coast of Washington is gradually warming at a depth of 500 meters, about a third of a mile down. That is the same depth where methane transforms from a solid to a gas. The research suggests that ocean warming could be triggering the ...

A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that long-term endurance training in a stable way alters the epigenetic pattern in the human skeletal muscle. The research team behind the study, which is being published in the journal Epigenetics, also found strong links between these altered epigenetic patterns and the activity in genes controlling improved metabolism and inflammation. The results may have future implications for prevention and treatment of heart disease, diabetes and obesity.

"It is well-established that being inactive is perilous, and that regular ...