INFORMATION:

The study was supported by a grant from Georgetown Lombardi's Fisher Center for Familial Research. Barac is supported by a GHUCCTSA KL2 award, which is funded in whole or in part with federal funds (KL2TR000102 previously KL2RR031974) from the National Institutes of Health, through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA).

About Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center

Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, part of Georgetown University Medical Center and MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, seeks to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer through innovative basic and clinical research, patient care, community education and outreach, and the training of cancer specialists of the future. Georgetown Lombardi is one of only 41 comprehensive cancer centers in the nation, as designated by the National Cancer Institute (grant #P30 CA051008), and the only one in the Washington, DC area. For more information, go to http://lombardi.georgetown.edu.

About Georgetown University Medical Center

Georgetown University Medical Center (GUMC) is an internationally recognized academic medical center with a three-part mission of research, teaching and patient care (through MedStar Health). GUMC's mission is carried out with a strong emphasis on public service and a dedication to the Catholic, Jesuit principle of cura personalis -- or "care of the whole person." The Medical Center includes the School of Medicine and the School of Nursing & Health Studies, both nationally ranked; Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, designated as a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute; and the Biomedical Graduate Research Organization, which accounts for the majority of externally funded research at GUMC including a Clinical and Translational Science Award from the National Institutes of Health. END

Common chemotherapy is not heart toxic in patients with BRCA1/2 mutations

2014-12-09

(Press-News.org) SAN ANTONIO -- Use of anthracycline-based chemotherapy, a common treatment for breast cancer, has negligible cardiac toxicity in women whose tumors have BRCA1/2 mutations -- despite preclinical evidence that such treatment can damage the heart.

The findings, to be presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), represent a unique effort between cardiologists and oncologists at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center and MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute in Washington to answer a vital clinical question.

"Our study was prompted by evidence from animal studies suggesting that mice with BRCA1/2 mutations in the heart were susceptible to heart damage -- treatment with anthracyclines led to reduced cardiac function and heart failure much more frequently in these mice than in those without these mutations," says the study's principal investigator, Ana Barac, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine and director of the cardio-oncology program at MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

"This was a very relevant question to explore for women with breast cancer who are BRCA1/2 mutation carriers because they often require treatment with anthracyclines," says Barac.

"Although there was no clinical suggestion of an excess risk of heart toxicity in mutation carriers, it is always important to carry out a study to evaluate whether findings in the preclinical setting -- in laboratory animals -- are actually valid concerns clinically," says co-author Claudine Isaacs, MD, co-director of the breast cancer program at Georgetown Lombardi.

"These results are very reassuring," Isaacs adds.

"Overall this is great news for our patients with BRCA mutations," says the study's co-investigator Filipa Lynce, MD, an oncologist with MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. "Our results provide reassurance that these patients do not appear to have increased heart toxicity when compared with non-mutation carriers," says Lynce, who will present the study at SABCS.

The study included 81 participants -- 39 BRCA1/2 carriers and 42 patients without the mutation. Women with metastatic disease and HER2-positive breast cancer were not included. The analysis also excluded patients who had history of hypertension because of its confounding effect on myocardial strain.

The participants had an echocardiogram 45 months, on average, after treatment with anthracyclines. The study used two measures to determine heart function: left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) -- the percentage of blood that leaves the heart after each contraction -- and global longitudinal strain (GLS), which correlates with LVEF but "is considered to be a more sensitive, global measure of cardiac function," Barac says.

The researchers found that most women had normal LVEF (91 percent) and normal GLS (85 percent). LVEF was borderline reduced (the heart pumped a little less blood than normal) in one BRCA1/2 mutation carrier and borderline or mildly reduced in six non-mutation carriers. They also found reduced GLS present in four mutation-carriers and seven non-mutation carriers.

"We found that mutation carriers who received anthracycline treatment do not have an increased risk of cardiac dysfunction, and that reduced cardiac function was very low in all patients, suggesting low risk of cardiac problems late after chemotherapy treatment," Barac says. "Our results are applicable only to patients without significant cardiovascular risk factors, particularly hypertension."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Three new Myriad studies highlighted at 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium

2014-12-09

SALT LAKE CITY, Utah, Dec. 9, 2014 - Myriad Genetics, Inc. (NASDAQ: MYGN) today announced results from a new study that demonstrated the ability of the myRisk™ Hereditary Cancer test to detect 105 percent more mutations in cancer causing genes than conventional BRCA testing alone. The Company also presented two key studies in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) that show the myChoice™ HRD test accurately predicted response to platinum-based therapy in patients with early-stage TNBC and that the BRACAnalysis® molecular diagnostic test significantly predicted ...

Temperature anomalies are warming faster than Earth's average

2014-12-09

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- It's widely known that the Earth's average temperature has been rising. But research by an Indiana University geographer and colleagues finds that spatial patterns of extreme temperature anomalies -- readings well above or below the mean -- are warming even faster than the overall average.

And trends in extreme heat and cold are important, said Scott M. Robeson, professor of geography in the College of Arts and Sciences at IU Bloomington. They have an outsized impact on water supplies, agricultural productivity and other factors related to human health ...

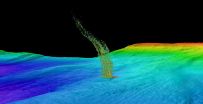

Warmer Pacific Ocean could release millions of tons of seafloor methane

2014-12-09

Off the West Coast of the United States, methane gas is trapped in frozen layers below the seafloor. New research from the University of Washington shows that water at intermediate depths is warming enough to cause these carbon deposits to melt, releasing methane into the sediments and surrounding water.

Researchers found that water off the coast of Washington is gradually warming at a depth of 500 meters, about a third of a mile down. That is the same depth where methane transforms from a solid to a gas. The research suggests that ocean warming could be triggering the ...

Long-term endurance training impacts muscle epigenetics

2014-12-09

A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that long-term endurance training in a stable way alters the epigenetic pattern in the human skeletal muscle. The research team behind the study, which is being published in the journal Epigenetics, also found strong links between these altered epigenetic patterns and the activity in genes controlling improved metabolism and inflammation. The results may have future implications for prevention and treatment of heart disease, diabetes and obesity.

"It is well-established that being inactive is perilous, and that regular ...

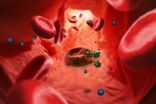

Nanotechnology against malaria parasites

2014-12-09

Malaria parasites invade human red blood cells; they then disrupt them and infect others. Researchers at the University of Basel and the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH) have now developed so-called nanomimics of host cell membranes that trick the parasites. This could lead to novel treatment and vaccination strategies in the fight against malaria and other infectious diseases. Their research results have been published in the scientific journal ACS Nano.

For many infectious diseases no vaccine currently exists. In addition, resistance against ...

Toxic fruits hold the key to reproductive success

2014-12-09

This news release is available in German.

In the course of evolution, animals have become adapted to certain food sources, sometimes even to plants or to fruits that are actually toxic. The driving forces behind such adaptive mechanisms are often unknown. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, have now discovered why the fruit fly Drosophila sechellia is adapted to the toxic fruits of the morinda tree. Drosophila sechellia females, which lay their eggs on these fruits, carry a mutation in a gene that inhibits egg production. ...

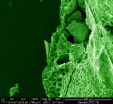

Stain every nerve

2014-12-09

Scientists can now explore nerves in mice in much greater detail than ever before, thanks to an approach developed by scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Monterotondo, Italy. The work, published online today in Nature Methods, enables researchers to easily use artificial tags, broadening the range of what they can study and vastly increasing image resolution.

"Already we've been able to see things that we couldn't see before," says Paul Heppenstall from EMBL, who led the research. "Structures such as nerves arranged around a hair on the skin; ...

New treatment strategy for epilepsy

2014-12-09

Researchers found out that the conformational defect in a specific protein causes Autosomal Dominant Lateral Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (ADLTE) which is a form of familial epilepsy. They showed that treatment with chemical corrector called "chemical chaperone" ameliorates increased seizure susceptibility in a mouse model of human epilepsy by correcting the conformational defect. This was published in Nature Medicine (December 8, 2014 electronic edition).

Mutations in the gene LGI1, encoding a secreted protein, cause familial temporal lobe epilepsy. The research group of ...

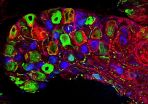

Turning biological cells to stone improves cancer and stem cell research

2014-12-09

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. -- Changing flesh to stone sounds like the work of a witch in a fairy tale.

But a new technique to transmute living cells into more permanent materials that defy rot and can endure high-powered probes is widening research opportunities for biologists who are developing cancer treatments, tracking stem cell evolution or even trying to understand how spiders vary the quality of the silk they spin.

The simple, silica-based method also offers materials scientists the ability to "fix" small biological entities like red blood cells into more commercially ...

The winds of Titan

2014-12-09

As sand dunes march across the Sahara, vast dunes cross the surface of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. New research from a refurbished NASA wind tunnel reveals the physics of how particles move in Titan's methane-laden winds and could help to explain why Titan's dunes form in the way they do. The work is published online Dec. 8 in the journal Nature.

"Conditions on Earth seem natural to us, but models from Earth won't work elsewhere," said Bruce White, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of California, Davis, and a co-author on the study. ...