(Press-News.org) As solar panels become less expensive and capable of generating more power, solar energy is becoming a more commercially viable alternative source of electricity. However, the photovoltaic cells now used to turn sunlight into electricity can only absorb and use a small fraction of that light, and that means a significant amount of solar energy goes untapped.

A new technology created by researchers from Caltech, and described in a paper published online in the October 30 issue of Science Express, represents a first step toward harnessing that lost energy.

Sunlight is composed of many wavelengths of light. In a traditional solar panel, silicon atoms are struck by sunlight and the atoms' outermost electrons absorb energy from some of these wavelengths of sunlight, causing the electrons to get excited. Once the excited electrons absorb enough energy to jump free from the silicon atoms, they can flow independently through the material to produce electricity. This is called the photovoltaic effect--a phenomenon that takes place in a solar panel's photovoltaic cells.

Although silicon-based photovoltaic cells can absorb light wavelengths that fall in the visible spectrum--light that is visible to the human eye--longer wavelengths such as infrared light pass through the silicon. These wavelengths of light pass right through the silicon and never get converted to electricity--and in the case of infrared, they are normally lost as unwanted heat.

"The silicon absorbs only a certain fraction of the spectrum, and it's transparent to the rest. If I put a photovoltaic module on my roof, the silicon absorbs that portion of the spectrum, and some of that light gets converted into power. But the rest of it ends up just heating up my roof," says Harry A. Atwater, the Howard Hughes Professor of Applied Physics and Materials Science; director, Resnick Sustainability Institute, who led the study.

Now, Atwater and his colleagues have found a way to absorb and make use of these infrared waves with a structure composed not of silicon, but entirely of metal.

The new technique they've developed is based on a phenomenon observed in metallic structures known as plasmon resonance. Plasmons are coordinated waves, or ripples, of electrons that exist on the surfaces of metals at the point where the metal meets the air.

While the plasmon resonances of metals are predetermined in nature, Atwater and his colleagues found that those resonances are capable of being tuned to other wavelengths when the metals are made into tiny nanostructures in the lab.

"Normally in a metal like silver or copper or gold, the density of electrons in that metal is fixed; it's just a property of the material," Atwater says. "But in the lab, I can add electrons to the atoms of metal nanostructures and charge them up. And when I do that, the resonance frequency will change."

"We've demonstrated that these resonantly excited metal surfaces can produce a potential"--an effect very similar to rubbing a glass rod with a piece of fur: you deposit electrons on the glass rod. "You charge it up, or build up an electrostatic charge that can be discharged as a mild shock," he says. "So similarly, exciting these metal nanostructures near their resonance charges up those metal structures, producing an electrostatic potential that you can measure."

This electrostatic potential is a first step in the creation of electricity, Atwater says. "If we can develop a way to produce a steady-state current, this could potentially be a power source. He envisions a solar cell using the plasmoelectric effect someday being used in tandem with photovoltaic cells to harness both visible and infrared light for the creation of electricity.

Although such solar cells are still on the horizon, the new technique could even now be incorporated into new types of sensors that detect light based on the electrostatic potential.

"Like all such inventions or discoveries, the path of this technology is unpredictable," Atwater says. "But any time you can demonstrate a new effect to create a sensor for light, that finding has almost always yielded some kind of new product."

INFORMATION:

This work was published in a paper titled, "Plasmoelectric Potentials in Metal Nanostructures." Other coauthors include first author Matthew T. Sheldon, a former postdoctoral scholar at Caltech; Ana M. Brown, an applied physics graduate student at Caltech; and Jorik van de Groep and Albert Polman from the FOM Institute AMOLF in Amsterdam. The study was funded by the Department of Energy, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, and an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship.

An international team of scientists has discovered the earliest known engravings from human ancestors on a 400,000 year-old fossilised shell from Java.

The discovery is the earliest known example of ancient humans deliberately creating pattern.

"It rewrites human history," said Dr Stephen Munro from School of Archaeology and Anthropology at The Australian National University (ANU).

"This is the first time we have found evidence for Homo erectus behaving this way," he said.

The newly discovered engravings resemble the previously oldest-known engravings, which are ...

Animals that regulate their body temperature through the external environment may be resilient to some climate change but not keep pace with rapid change leading to potentially disastrous outcomes for biodiversity.

A study by the University of Sydney and University of Queensland showed many animals can modify the function of their cells and organs to compensate for changes in the climate and have done so in the past, but the researchers warn that the current rate of climate change will outpace animals' capacity for compensation (or acclimation).

The research has just ...

SAN ANTONIO -- Use of anthracycline-based chemotherapy, a common treatment for breast cancer, has negligible cardiac toxicity in women whose tumors have BRCA1/2 mutations -- despite preclinical evidence that such treatment can damage the heart.

The findings, to be presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), represent a unique effort between cardiologists and oncologists at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center and MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute in Washington to answer a vital clinical question.

"Our study was prompted by evidence from ...

SALT LAKE CITY, Utah, Dec. 9, 2014 - Myriad Genetics, Inc. (NASDAQ: MYGN) today announced results from a new study that demonstrated the ability of the myRisk™ Hereditary Cancer test to detect 105 percent more mutations in cancer causing genes than conventional BRCA testing alone. The Company also presented two key studies in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) that show the myChoice™ HRD test accurately predicted response to platinum-based therapy in patients with early-stage TNBC and that the BRACAnalysis® molecular diagnostic test significantly predicted ...

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- It's widely known that the Earth's average temperature has been rising. But research by an Indiana University geographer and colleagues finds that spatial patterns of extreme temperature anomalies -- readings well above or below the mean -- are warming even faster than the overall average.

And trends in extreme heat and cold are important, said Scott M. Robeson, professor of geography in the College of Arts and Sciences at IU Bloomington. They have an outsized impact on water supplies, agricultural productivity and other factors related to human health ...

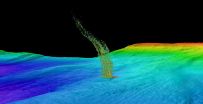

Off the West Coast of the United States, methane gas is trapped in frozen layers below the seafloor. New research from the University of Washington shows that water at intermediate depths is warming enough to cause these carbon deposits to melt, releasing methane into the sediments and surrounding water.

Researchers found that water off the coast of Washington is gradually warming at a depth of 500 meters, about a third of a mile down. That is the same depth where methane transforms from a solid to a gas. The research suggests that ocean warming could be triggering the ...

A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that long-term endurance training in a stable way alters the epigenetic pattern in the human skeletal muscle. The research team behind the study, which is being published in the journal Epigenetics, also found strong links between these altered epigenetic patterns and the activity in genes controlling improved metabolism and inflammation. The results may have future implications for prevention and treatment of heart disease, diabetes and obesity.

"It is well-established that being inactive is perilous, and that regular ...

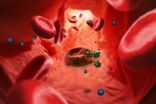

Malaria parasites invade human red blood cells; they then disrupt them and infect others. Researchers at the University of Basel and the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH) have now developed so-called nanomimics of host cell membranes that trick the parasites. This could lead to novel treatment and vaccination strategies in the fight against malaria and other infectious diseases. Their research results have been published in the scientific journal ACS Nano.

For many infectious diseases no vaccine currently exists. In addition, resistance against ...

This news release is available in German.

In the course of evolution, animals have become adapted to certain food sources, sometimes even to plants or to fruits that are actually toxic. The driving forces behind such adaptive mechanisms are often unknown. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, have now discovered why the fruit fly Drosophila sechellia is adapted to the toxic fruits of the morinda tree. Drosophila sechellia females, which lay their eggs on these fruits, carry a mutation in a gene that inhibits egg production. ...

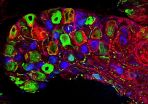

Scientists can now explore nerves in mice in much greater detail than ever before, thanks to an approach developed by scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Monterotondo, Italy. The work, published online today in Nature Methods, enables researchers to easily use artificial tags, broadening the range of what they can study and vastly increasing image resolution.

"Already we've been able to see things that we couldn't see before," says Paul Heppenstall from EMBL, who led the research. "Structures such as nerves arranged around a hair on the skin; ...