(Press-News.org) Johns Hopkins researchers have developed a sugar-based molecular microcapsule that eliminates the toxicity of an anticancer agent developed a decade ago at Johns Hopkins, called 3-bromopyruvate, or 3BrPA, in studies of mice with implants of human pancreatic cancer tissue. The encapsulated drug packed a potent anticancer punch, stopping the progression of tumors in the mice, but without the usual toxic effects.

"We developed 3BrPA to target a hallmark of cancer cells, namely their increased dependency on glucose compared with normal cells. But the nonencapsulated drug is toxic to healthy tissues and inactivated as it navigates through the blood, so finding a way to encapsulate the drug and protect normal tissues extends its promise in many cancers as it homes in on tumor cells," says Jean-Francois Geschwind, M.D., chief of the Division of Interventional Radiology at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

The Johns Hopkins team used a microshell made of a sugar-based polymer called cyclodextrin to protect the 3BrPA drug molecules from disintegrating early and to guard healthy tissue from the drug's toxic effects, such as weight loss, hypothermia and lethal hypoglycemic shock.

Geschwind, a professor in the Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Science at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and its Kimmel Cancer Center, and others at Johns Hopkins have been studying the experimental drug as a cancer treatment for over a decade because of its ability to block a key metabolic pathway of cancer cells.

Most cancer cells, he explains, rely on the use of glucose to thrive, a process known as the Warburg effect, for Otto Heinrich Warburg, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology for the discovery in 1931. By using the same cellular channels that funnel glucose into a cancer cell, 3BrPA can travel inside the cancer cell and block its glucose metabolic pathway, Geschwind says.

However, animal studies have shown that in its free, nonencapsulated state, the drug is very toxic, says Geschwind.

The toxicity associated with the free-form version of the drug, he says, has prevented physicians from using the drug as a systemic treatment in people, one that can travel throughout the whole body.

In a report about their study published online Oct. 17 in Clinical Cancer Research, the researchers described minimal or zero tumor progression in mice treated with the microencapsulated 3BrPA. By contrast, a signal of tumor activity increased sixty-fold in mice treated with the widely used chemotherapy drug gemcitabine. Activity increased 140-fold in mice who received the drug without encapsulation.

Specifically, daily injections of nonencapsulated 3BrPA were highly toxic to the animals, as only 28 percent of the animals survived the 28-day treatment. All of the mice who received the encapsulated drug survived to the end of the study.

Geschwind says the "extremely promising results" of the study make the encapsulated drug a good candidate for clinical trials, particularly for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. These cancers rank as the fourth most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the world, with a five-year survival rate of less than 5 percent. In the mouse studies, the encapsulated medication also reduced the metastatic spread of pancreatic cancer cells.

INFORMATION:

Other Johns Hopkins researchers who contributed to the study include Julius Chapiro, Surojit Sur, Lynn Jeanette Savic, Shanmugasundaram Ganapathy-Kaniappan, Juvenal Reyes, Rafael Duran, Sivarajan Chettiar-Thiruganasambandam, Cassandra Rae Moats, MingDe Lin, Weibo Luo, Phuoc T. Tran, Joseph M. Herman, Gregg L. Semenza, Andrew J. Ewald and Bert Vogelstein.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Institute grants (R01 CA160771, P30 CA006973, NCRR UL1 RR 025005 and DOD CDMRP, W81XWH-11-1-0343, K99-CA168746, R01CA166348), the Rolf W. Gunther Foundation for Radiological Science, the American Cancer Society (RSG-12-141-01-CSM), the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, and the Lustgarten Foundation.

Geschwind has served as a consultant for BTG, Bayer HealthCare, Guerbet, Philips Healthcare and Boston-Scientific. He has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense, Society of Interventional Radiology, Radiological Society of North America, BTG, Bayer HealthCare, Philips Healthcare, Threshold and Guerbet. He is the CEO and founder of PreScience Labs, which has licensed 3BrPA from Johns Hopkins.

Read the study in Clinical Cancer Research: http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/early/2014/10/17/1078-0432.CCR-14-1271.abstract

Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center

Office of Public Affairs

Media Contacts:

Vanessa Wasta, 410-614-2916, wasta@jhmi.edu

Amy Mone, 410-614-2915, amone@jhmi.edu

In a development that holds promise for future magnetic memory and logic devices, researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and Cornell University successfully used an electric field to reverse the magnetization direction in a multiferroic spintronic device at room temperature. This demonstration, which runs counter to conventional scientific wisdom, points a new way towards spintronics and smaller, faster and cheaper ways of storing and processing data.

"Our work shows that 180-degree magnetization switching ...

Premature ovarian failure, also known as primary ovarian insufficiency (POI), affects 1% of all women worldwide. In most cases, the exact cause of the condition, which is often associated with infertility, is difficult to determine.

A new Tel Aviv University study throws a spotlight on a previously-unidentified cause of POI: a unique mutation in a gene called SYCE1 that has not been previously associated with POI in humans. The research, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, was led by Dr. Liat de Vries and Prof. Lina Basel-Vanagaite of TAU's ...

A new species of short-necked marine reptile from the Triassic period has been discovered in China, according to a study published December 17, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Xiao-hong Chen from Wuhan Centre of China Geological Survey and colleagues.

Hupehsuchia is a group of mysterious Triassic marine reptiles which have, so far, only been found in two counties in Hubei Province, China. The group is known by its modestly long neck, with nine to ten cervical vertebrae, but the authors of this study recently discovered a new species of Hupehsuchia that may ...

A network of nine reference sites off the Australian coast is providing the latest physical, chemical, and biological information to help scientists better understand Australia's coastal seas, according to a study published December 17, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Tim Lynch from CSIRO, Australia and colleagues.

Sustained oceanic observations allow scientists to track changes in oceanography and ecosystems. To address this, the Australian Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) implemented a network of nine National Reference Stations (NRS). The network ...

Like human patients, mice with a form of Duchenne muscular dystrophy undergo progressive muscle degeneration and accumulate connective tissue as they age. Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have found that the fault may lie at least partly in the stem cells that surround the muscle fibers.

They've found that during the course of the disease, the stem cells become less able to make new muscle and instead begin to express genes involved in the formation of connective tissue. Excess connective tissue -- a condition called fibrosis -- can accumulate ...

Bird migration is an impressive phenomenon, but why birds often travel huge distances to and from their breeding grounds in the far North is still very unclear. Suggestions include that the birds profit from longer daylight hours, or that there are fewer predators. Researchers from the University of Groningen and the NIOO-KNAW Vogeltrekstation, the Dutch centre for bird migration and demographics, have discovered a new explanation.

They investigated barnacle geese breeding on Spitsbergen and compared them with birds of the same species that did not migrate but stayed ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- The best way to protect wild spinner dolphins in Hawaii while also maintaining the local tourism industry that depends on them is through a combination of federal regulations and community-based conservation measures, finds a new study from Duke University.

Each year, hundreds of thousands of tourists to Hawaii pay to have up-close encounters with the animals, swimming with them in shallow bays the dolphins use as safe havens for daytime rest. But as the number of tours increases, so do the pressures they place on the resting dolphins.

The Duke study ...

A new catalytic process is able to convert what was once considered biomass waste into lucrative chemical products that can be used in fragrances, flavorings or to create high-octane fuel for racecars and jets.

A team of researchers from Purdue University's Center for Direct Catalytic Conversion of Biomass to Biofuels, or C3Bio, has developed a process that uses a chemical catalyst and heat to spur reactions that convert lignin into valuable chemical commodities. Lignin is a tough and highly complex molecule that gives the plant cell wall its rigid structure.

Mahdi ...

A close look at the night sky reveals that stars don't like to be alone; instead, they congregate in clusters, in some cases containing as many as several million stars. Until recently, the oldest of these populous star clusters were considered well understood, with the stars in a single group having formed at different times, over periods of more than 300 million years. Yet new research published online today in the journal Nature suggests that the star formation in these clusters is more complex.

Using data from the Hubble Space Telescope, a team of researchers at the ...

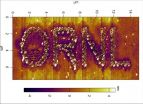

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., Dec. 17, 2014--Scientists at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory have used advanced microscopy to carve out nanoscale designs on the surface of a new class of ionic polymer materials for the first time. The study provides new evidence that atomic force microscopy, or AFM, could be used to precisely fabricate materials needed for increasingly smaller devices.

Polymerized ionic liquids have potential applications in technologies such as lithium batteries, transistors and solar cells because of their high ionic conductivity and unique ...