(Press-News.org) Western U.S. forests killed by the mountain pine beetle epidemic are no more at risk to burn than healthy Western forests, according to new findings by the University of Colorado Boulder that fly in the face of both public perception and policy.

The CU-Boulder study authors looked at the three peak years of Western wildfires since 2002, using maps produced by federal land management agencies. The researchers superimposed maps of areas burned in the West in 2006, 2007 and 2012 on maps of areas identified as infested by mountain pine beetles.

The area of forests burned during those three years combined were responsible for 46 percent of the total area burned in the West from 2002 to 2013.

"The bottom line is that forests infested by the mountain pine beetle are not more likely to burn at a regional scale," said CU-Boulder postdoctoral researcher Sarah Hart, lead study author. "We found that alterations in the forest infested by the mountain pine beetle are not as important in fires as overriding drivers like climate and topography."

A paper on the subject is being published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study was funded by the Wilburforce Foundation and the National Science Foundation. The Wilburforce Foundation is a private, philanthropic group that funds conservation science in the Western U.S. and western Canada.

Co-authors on the new study include CU-Boulder Research Scientist Tania Schoennagel of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, CU-Boulder geography Professor Thomas Veblen and CU-Boulder doctoral student Teresa Chapman.

The impetus for the study was in part the severe and extensive native bark beetle outbreaks in response to warming temperatures and drought over the past 15 years that have caused dramatic tree mortality from Alaska to the American Southwest, said Hart. Mountain pine beetles killed more than 24,700 square miles of forest across the Western U.S. in that time period, an area nearly as large as Lake Superior.

"The question was still out there about whether bark beetle outbreaks really have affected subsequent fires," Hart said. "We wanted to take a broad-scale, top-down approach and look at all of the fires across the Western U.S. and see the emergent effects of bark beetle kill on fires."

Previous studies examining the effect of bark beetles on wildfire activity have been much smaller in scale, assessing the impact of the insects on one or only a few fires, said Hart. This is the first study to look at trends from multiple years across the entire Western U.S. While several of the small studies indicated bark beetle activity was not a significant factor, some computer modeling studies conclude the opposite.

The CU-Boulder team used ground, airplane and satellite data from the U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Geological Survey to produce maps of both beetle infestation and the extent of wildfire burns across the West.

The two factors that appear to play the most important roles in larger Western forest fires include climate change -- temperatures in the West have risen by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1970 as a result of increasing greenhouse gases -- and a prolonged Western drought, which has been ongoing since 2002.

"What we are seeing in this study is that at broad scales, fire does not necessarily follow mountain pine beetles," said Schoennagel. "It's well known, however, that fire does follow drought."

The 2014 Farm Bill allocated $200 million to reduce the risk of insect outbreak, disease and subsequent wildfire across roughly 70,000 square miles of National Forest land in the West, said Hart. "We believe the government needs to be smart about how these funds are spent based on what the science is telling us," she said. "If the money is spent on increasing the safety of firefighters, for example, or protecting homes at risk of burning from forest fires, we think that makes sense."

Firefighting in forests that have been killed by mountain pine beetles will continue to be a big challenge, said Schoennagel. But thinning such forests in an attempt to mitigate the chance of burning is probably not an effective strategy.

"I think what is really powerful about our study is its broad scale," said Hart. "It is pretty conclusive that we are not seeing an increase in areas burned even as we see an increase in the mountain pine beetle outbreaks," she said.

"These results refute the assumption that increased bark beetle activity has increased area burned," wrote the researchers in PNAS. "Therefore, policy discussions should focus on societal adaptation to the effect of the underlying drivers: warmer temperatures and increased drought."

INFORMATION:

-CU-

Contact:

Sarah Hart 303-492-4986

sarah.hart@colorado.edu

Tania Schoennagel, 303-818-5166

tania.schoennagel@colorado.edu

Thomas Veblen, 303-492-8528

thomas.veblen@colorado.edu

Jim Scott, CU-Boulder media relations, 303-492-3114

jim.scott@colorado.edu

A molecule that prevents Type 1 diabetes in mice has provoked an immune response in human cells, according to researchers at National Jewish Health and the University of Colorado. The findings, published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that a mutated insulin fragment could be used to prevent Type 1 diabetes in humans.

"The incidence of Type 1 diabetes is increasing dramatically," said John Kappler, PhD, professor of Biomedical Research at National Jewish Health. "Our findings provide an important proof of concept in humans for a ...

Non-native plants are commonly listed as invasive species, presuming that they cause harm to the environment at both global and regional scales. New research by scientists at the University of York has shown that non-native plants - commonly described as having negative ecological or human impacts - are not a threat to floral diversity in Britain.

Using repeat census field survey data for British plants from 1990 and 2007, Professor Chris Thomas and Dr Georgina Palmer from the Department of Biology at York analysed changes in the cover and diversity of native and non-native ...

A 60-year-old maths problem first put forward by Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi has been solved by researchers at the University of East Anglia, the Università degli Studi di Torino (Italy) and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (US).

In 1955, a team of physicists, computer scientists and mathematicians led by Fermi used a computer for the first time to try and solve a numerical experiment.

The outcome of the experiment wasn't what they were expecting, and the complexity of the problem underpinned the then new field of non-linear physics and paved the way for six ...

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University who develop snake-like robots have picked up a few tricks from real sidewinder rattlesnakes on how to make rapid and even sharp turns with their undulating, modular device.

Working with colleagues at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Zoo Atlanta, they have analyzed the motions of sidewinders and tested their observations on CMU's snake robots. They showed how the complex motion of a sidewinder can be described in terms of two wave motions - vertical and horizontal body waves - and how changing the phase and amplitude of ...

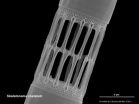

Troy, N.Y. - A team of researchers, including Rensselaer professor Morgan Schaller, has used mathematical modeling to show that continental erosion over the last 40 million years has contributed to the success of diatoms, a group of tiny marine algae that plays a key role in the global carbon cycle. The research was published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Diatoms consume 70 million tons of carbon from the world's oceans daily, producing organic matter, a portion of which sinks and is buried in deep ocean sediments. Diatoms account for over ...

Archaeologists working in Guatemala have unearthed new information about the Maya civilization's transition from a mobile, hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a sedentary way of life.

Led by University of Arizona archaeologists Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan, the team's excavations of the ancient Maya lowlands site of Ceibal suggest that as the society transitioned from a heavy reliance on foraging to farming, mobile communities and settled groups co-existed and may have come together to collaborate on construction projects and participate in public ceremonies.

The findings, ...

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. - March 23, 2015 - The results of a blood test done immediately after heart surgery can be a meaningful indicator of postoperative stroke risk, a study by researchers at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center has found.

An acutely elevated level of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) - a measure of kidney function detected through blood testing - was the most powerful predictor of postoperative stroke among the study's subjects.

Up to 9 percent of cardiac surgery patients suffer post-operative stroke, and these events are significantly more serious and more frequently ...

The concept was simple: If two compounds each individually show promise in preventing colon cancer, surely it's worth trying the two together to see if even greater impact is possible.

In this instance, Case Western Reserve cancer researcher Li Li, MD, PhD, could not have been more prescient.

Not only did the combination of the two improve outcomes in animal studies, but the dual-compound effect was dramatically better than either option alone. Even better, these impressive results required only modest amounts of metformin and Vitamin D3, making concerns about side ...

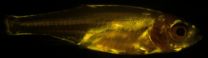

DURHAM, N.C. - Scientists have known for some time that people who carry a lot of weight around their bellies are more likely to develop diabetes and heart disease than those who have bigger hips and thighs. But what hasn't been clear is why fat accumulates in different places to produce these classic "apple" and "pear" shapes.

Now, researchers have discovered that a gene called Plexin D1 appears to control both where fat is stored and how fat cells are shaped, known factors in health and the risk of future disease.

Acting on a pattern that emerged in an earlier study ...

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. -- MARCH 23, 2015) Research led by scientists at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital has identified key molecules that trigger the immune system to launch an attack on the bacterium that causes tularemia. The research was published online March 16 in Nature Immunology.

The team, led by Thirumala-Devi Kanneganti, Ph.D., a member of the St. Jude Department of Immunology, found key receptors responsible for sensing DNA in cells infected by the tularemia-causing bacterium, Francisella. Tularemia is a highly infectious disease that kills more than 30 percent ...