(Press-News.org) Jupiter may have swept through the early solar system like a wrecking ball, destroying a first generation of inner planets before retreating into its current orbit, according to a new study published March 23 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The findings help explain why our solar system is so different from the hundreds of other planetary systems that astronomers have discovered in recent years.

"Now that we can look at our own solar system in the context of all these other planetary systems, one of the most interesting features is the absence of planets inside the orbit of Mercury," said Gregory Laughlin, professor and chair of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz and coauthor of the paper. "The standard issue planetary system in our galaxy seems to be a set of super-Earths with alarmingly short orbital periods. Our solar system is looking increasingly like an oddball."

The new paper explains not only the "gaping hole" in our inner solar system, he said, but also certain characteristics of Earth and the other inner rocky planets, which would have formed later than the outer planets from a depleted supply of planet-forming material.

Laughlin and coauthor Konstantin Batygin explored the implications of a leading scenario for the formation of Jupiter and Saturn. In that scenario, proposed by another team of astronomers in 2011 and known as the "Grand Tack," Jupiter first migrated inward toward the sun until the formation of Saturn caused it to reverse course and migrate outward to its current position. Batygin, who first worked with Laughlin as an undergraduate at UC Santa Cruz and is now an assistant professor of planetary science at the California Institute of Technology, performed numerical calculations to see what would happen if a set of rocky planets with close-in orbits had formed prior to Jupiter's inward migration.

At that time, it's plausible that rocky planets with deep atmospheres would have been forming close to the sun from a dense disk of gas and dust, on their way to becoming typical "super-Earths" like so many of the exoplanets astronomers have found around other stars. As Jupiter moved inward, however, gravitational perturbations from the giant planet would have swept the inner planets (and smaller planetesimals and asteroids) into close-knit, overlapping orbits, setting off a series of collisions that smashed all the nascent planets into pieces.

"It's the same thing we worry about if satellites were to be destroyed in low-Earth orbit. Their fragments would start smashing into other satellites and you'd risk a chain reaction of collisions. Our work indicates that Jupiter would have created just such a collisional cascade in the inner solar system," Laughlin said.

The resulting debris would then have spiraled into the sun under the influence of a strong "headwind" from the dense gas still swirling around the sun. The ingoing avalanche would have destroyed any newly-formed super-Earths by driving them into the sun. A second generation of inner planets would have formed later from the depleted material that was left behind, consistent with evidence that our solar system's inner planets are younger than the outer planets. The resulting inner planets--Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars--are also less massive and have much thinner atmospheres than would otherwise be expected, Laughlin said.

"One of the predictions of our theory is that truly Earth-like planets, with solid surfaces and modest atmospheric pressures, are rare," he said.

Planet hunters have detected well over a thousand exoplanets orbiting stars in our galaxy, including nearly 500 systems with multiple planets. What has emerged from these observations as the "typical" planetary system is one consisting of a few planets with masses several times larger than the Earth's (called super-Earths) orbiting much closer to their host star than Mercury is to the sun. In systems with giant planets similar to Jupiter, they also tend to be much closer to their host stars than the giant planets in our solar system. The rocky inner planets of our solar system, with relatively low masses and thin atmospheres, may turn out to be fairly anomalous.

According to Laughlin, the formation of giant planets like Jupiter is somewhat rare, but when it occurs the giant planet usually migrates inward and ends up at an orbital distance similar to Earth's. Only the formation of Saturn in our own solar system pulled Jupiter back out and allowed Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars to form. Therefore, another prediction of the paper is that systems with giant planets at orbital periods of more than about 100 days would be unlikely to host multiple close-in planets, Laughlin said.

"This kind of theory, where first this happened and then that happened, is almost always wrong, so I was initially skeptical," he said. "But it actually involves generic processes that have been extensively studied by other researchers. There is a lot of evidence that supports the idea of Jupiter's inward and then outward migration. Our work looks at the consequences of that. Jupiter's 'Grand Tack' may well have been a 'Grand Attack' on the original inner solar system."

INFORMATION:

'Attractive' male birds that mate with many females aren't passing on the best genes to their offspring, according to new UCL research which found promiscuity in male birds leads to small, genetic faults in the species' genome.

Although minor, these genetic flaws may limit how well future generations can adapt to changing environments.

The study, published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and funded by the European Research Council, shows for the first time the power of sexual selection - where some individuals are better at securing mates ...

Leprosy is a chronic infection of the skin, peripheral nerves, eyes and mucosa of the upper respiratory tract, affecting over a quarter million people worldwide. Its symptoms can be gruesome and devastating, as the bacteria reduce sensitivity in the body, resulting in skin lesions, nerve damage and disabilities. Until recently, leprosy was attributed to a single bacterium, Mycobacterium leprae; we now suspect that its close relative, Mycobacterium lepromatosis, might cause a rare but severe form of leprosy. Scientists at École Polytechnique Fe?de?rale de Lausanne (EPFL) ...

Western U.S. forests killed by the mountain pine beetle epidemic are no more at risk to burn than healthy Western forests, according to new findings by the University of Colorado Boulder that fly in the face of both public perception and policy.

The CU-Boulder study authors looked at the three peak years of Western wildfires since 2002, using maps produced by federal land management agencies. The researchers superimposed maps of areas burned in the West in 2006, 2007 and 2012 on maps of areas identified as infested by mountain pine beetles.

The area of forests burned ...

A molecule that prevents Type 1 diabetes in mice has provoked an immune response in human cells, according to researchers at National Jewish Health and the University of Colorado. The findings, published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that a mutated insulin fragment could be used to prevent Type 1 diabetes in humans.

"The incidence of Type 1 diabetes is increasing dramatically," said John Kappler, PhD, professor of Biomedical Research at National Jewish Health. "Our findings provide an important proof of concept in humans for a ...

Non-native plants are commonly listed as invasive species, presuming that they cause harm to the environment at both global and regional scales. New research by scientists at the University of York has shown that non-native plants - commonly described as having negative ecological or human impacts - are not a threat to floral diversity in Britain.

Using repeat census field survey data for British plants from 1990 and 2007, Professor Chris Thomas and Dr Georgina Palmer from the Department of Biology at York analysed changes in the cover and diversity of native and non-native ...

A 60-year-old maths problem first put forward by Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi has been solved by researchers at the University of East Anglia, the Università degli Studi di Torino (Italy) and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (US).

In 1955, a team of physicists, computer scientists and mathematicians led by Fermi used a computer for the first time to try and solve a numerical experiment.

The outcome of the experiment wasn't what they were expecting, and the complexity of the problem underpinned the then new field of non-linear physics and paved the way for six ...

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University who develop snake-like robots have picked up a few tricks from real sidewinder rattlesnakes on how to make rapid and even sharp turns with their undulating, modular device.

Working with colleagues at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Zoo Atlanta, they have analyzed the motions of sidewinders and tested their observations on CMU's snake robots. They showed how the complex motion of a sidewinder can be described in terms of two wave motions - vertical and horizontal body waves - and how changing the phase and amplitude of ...

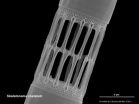

Troy, N.Y. - A team of researchers, including Rensselaer professor Morgan Schaller, has used mathematical modeling to show that continental erosion over the last 40 million years has contributed to the success of diatoms, a group of tiny marine algae that plays a key role in the global carbon cycle. The research was published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Diatoms consume 70 million tons of carbon from the world's oceans daily, producing organic matter, a portion of which sinks and is buried in deep ocean sediments. Diatoms account for over ...

Archaeologists working in Guatemala have unearthed new information about the Maya civilization's transition from a mobile, hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a sedentary way of life.

Led by University of Arizona archaeologists Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan, the team's excavations of the ancient Maya lowlands site of Ceibal suggest that as the society transitioned from a heavy reliance on foraging to farming, mobile communities and settled groups co-existed and may have come together to collaborate on construction projects and participate in public ceremonies.

The findings, ...

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. - March 23, 2015 - The results of a blood test done immediately after heart surgery can be a meaningful indicator of postoperative stroke risk, a study by researchers at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center has found.

An acutely elevated level of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) - a measure of kidney function detected through blood testing - was the most powerful predictor of postoperative stroke among the study's subjects.

Up to 9 percent of cardiac surgery patients suffer post-operative stroke, and these events are significantly more serious and more frequently ...