(Press-News.org) MIT researchers have developed a new, ultrasensitive magnetic-field detector that is 1,000 times more energy-efficient than its predecessors. It could lead to miniaturized, battery-powered devices for medical and materials imaging, contraband detection, and even geological exploration.

Magnetic-field detectors, or magnetometers, are already used for all those applications. But existing technologies have drawbacks: Some rely on gas-filled chambers; others work only in narrow frequency bands, limiting their utility.

Synthetic diamonds with nitrogen vacancies (NVs) -- defects that are extremely sensitive to magnetic fields -- have long held promise as the basis for efficient, portable magnetometers. A diamond chip about one-twentieth the size of a thumbnail could contain trillions of nitrogen vacancies, each capable of performing its own magnetic-field measurement.

The problem has been aggregating all those measurements. Probing a nitrogen vacancy requires zapping it with laser light, which it absorbs and re-emits. The intensity of the emitted light carries information about the vacancy's magnetic state.

"In the past, only a small fraction of the pump light was used to excite a small fraction of the NVs," says Dirk Englund, the Jamieson Career Development Assistant Professor in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and one of the designers of the new device. "We make use of almost all the pump light to measure almost all of the NVs."

The MIT researchers report their new device in the latest issue of Nature Physics. First author on the paper is Hannah Clevenson, a graduate student in electrical engineering who is advised by senior authors Englund and Danielle Braje, a physicist at MIT Lincoln Laboratory. They're joined by Englund's students Matthew Trusheim and Carson Teale (who's also at Lincoln Lab) and by Tim Schröder, a postdoc in MIT's Research Laboratory of Electronics.

Telling absence

A pure diamond is a lattice of carbon atoms, which don't interact with magnetic fields. A nitrogen vacancy is a missing atom in the lattice, adjacent to a nitrogen atom. Electrons in the vacancy do interact with magnetic fields, which is why they're useful for sensing.

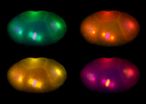

When a light particle -- a photon -- strikes an electron in a nitrogen vacancy, it kicks it into a higher energy state. When the electron falls back down into its original energy state, it may release its excess energy as another photon. A magnetic field, however, can flip the electron's magnetic orientation, or spin, increasing the difference between its two energy states. The stronger the field, the more spins it will flip, changing the brightness of the light emitted by the vacancies.

Making accurate measurements with this type of chip requires collecting as many of those photons as possible. In previous experiments, Clevenson says, researchers often excited the nitrogen vacancies by directing laser light at the surface of the chip.

"Only a small fraction of the light is absorbed," she says. "Most of it just goes straight through the diamond. We gain an enormous advantage by adding this prism facet to the corner of the diamond and coupling the laser into the side. All of the light that we put into the diamond can be absorbed and is useful."

Covering the bases

The researchers calculated the angle at which the laser beam should enter the crystal so that it will remain confined, bouncing off the sides -- like a tireless cue ball ricocheting around a pool table -- in a pattern that spans the length and breadth of the crystal before all of its energy is absorbed.

"You can get close to a meter in path length," Englund says. "It's as if you had a meter-long diamond sensor wrapped into a few millimeters." As a consequence, the chip uses the pump laser's energy 1,000 times as efficiently as its predecessors did.

Because of the geometry of the nitrogen vacancies, the re-emitted photons emerge at four distinct angles. A lens at one end of the crystal can collect 20 percent of them and focus them onto a light detector, which is enough to yield a reliable measurement.

INFORMATION:

Dividing cells--whether they're in an embryo or an adult--rely on the right processes happening at the right time to turn out healthy.

Now, researchers at the University of Iowa have identified a mechanism that dividing cells in worms use to ensure their proper development, and they believe the same process could be going on in humans. The mechanism, unknown until now, describes one part of the cell, called the centrosome, as an "internal timekeeper"--like a train conductor. A crucial protein in charge of gene expression, beta-catenin, is described as a "hitchhiker"--it ...

Physical activity that makes you puff and sweat is key to avoiding an early death, a large Australian study of middle-aged and older adults has found.

The researchers followed 204,542 people for more than six years, and compared those who engaged in only moderate activity (such as gentle swimming, social tennis, or household chores) with those who included at least some vigorous activity (such as jogging, aerobics or competitive tennis).

They found that the risk of mortality for those who included some vigorous activity was 9 to 13 per cent lower, compared with those ...

Leading coral reef scientists say Australia could restore the Great Barrier Reef to its former glory through better policies that focus on science, protection and conservation.

In a paper published in the journal Nature Climate Change, the authors argue that all the stressors on the Reef need to be reduced for it to recover.

An Australian Government report into the state of the Great Barrier Reef found that its condition in 2014 was "poor and expected to further deteriorate in the future". In the past 40 years, the Reef has lost more than half of its coral cover and ...

Many nursing home residents who underwent lower extremity revascularization died, did not walk or had functional decline following the procedure, which is commonly used to treat leg pain caused by peripheral arterial disease, wounds that will not heal or worsening gangrene, according to an article published online by JAMA Internal Medicine.

Lower extremity revascularization is often performed so patients with peripheral arterial disease can maintain the ability to walk, which is a key component of functional independence. But outcomes among patients with high levels of ...

Quality of life was good and cognitive function was similar in patients with cardiac arrest who received targeted body-temperature management as a neuroprotective measure in intensive care units in Europe and Australia, according to an article published online by JAMA Neurology.

Brain injury is the primary cause of death for patients treated in intensive care units after suffering cardiac arrest (CA) outside of a hospital. Targeted temperature management (TTM) has been implemented as a neuroprotective treatment for comatose CA survivors because of reports of improved ...

Application of pediatric guidelines for lipid levels for persons 17 to 21 years of age who have elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels would result in statin treatment for more than 400,000 additional young people than the adult guidelines, according to an article published online by JAMA Pediatrics.

Adolescence is a common time for the emergence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including abnormal cholesterol levels. The 2011 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in ...

Only a few U.S. nursing home residents who undergo lower extremity revascularization procedures are alive and ambulatory a year after surgery, according to UCSF researchers, and most patients still alive gained little, if any, function.

The study appears in the April 6 issue of JAMA Internal Medicine.

"Our findings can inform conversations among physicians, patients and families about the risks and expected outcomes of surgery and whether the surgery is likely to allow patients to achieve their treatment goals," said senior author Emily Finlayson, MD, MS, associate ...

Seventy per cent of glacier ice in British Columbia and Alberta could disappear by the end of the 21st century, creating major problems for local ecosystems, power supplies, and water quality, according to a new study by University of British Columbia researchers.

The study found that while warming temperatures are threatening glaciers in Western Canada, not all glaciers are retreating at the same rate. The Rocky Mountains, in the drier interior, could lose up to 90 per cent of its glaciers. The wetter coastal mountains in northwestern B.C. are only expected to lose about ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Duke researchers have developed a new method to precisely control when genes are turned on and active.

The new technology allows researchers to turn on specific gene promoters and enhancers -- pieces of the genome that control gene activity -- by chemically manipulating proteins that package DNA. This web of biomolecules that supports and controls gene activity is known as the epigenome.

The researchers say having the ability to steer the epigenome will help them explore the roles that particular promoters and enhancers play in cell fate or the risk ...

Stanford University scientists have invented the first high-performance aluminum battery that's fast-charging, long-lasting and inexpensive. Researchers say the new technology offers a safe alternative to many commercial batteries in wide use today.

"We have developed a rechargeable aluminum battery that may replace existing storage devices, such as alkaline batteries, which are bad for the environment, and lithium-ion batteries, which occasionally burst into flames," said Hongjie Dai, a professor of chemistry at Stanford. "Our new battery won't catch fire, even if you ...