(Press-News.org) Scientists from the Institut Pasteur and CNRS, in collaboration with scientists from the Institut Gustave Roussy and CEA, have succeeded in restoring normal activity in cells isolated from patients with the premature aging disease Cockayne syndrome. They have uncovered the role played in these cells by an enzyme, the HTRA3 protease.

This enzyme is overexpressed in Cockayne syndrome patient cells, and leads to mitochondrial defects, which in turn play a crucial role in the appearance of symptoms leading to aging in affected children. These findings, published in the journal PNAS Plus, describe one of the hitherto unknown mechanisms responsible for premature aging. They could also shed light on the normal aging process.

Rare genetic diseases cause accelerated premature aging. To date, there is no treatment for these pathologies. Understanding the causes of premature aging diseases may also help elucidating the process of normal aging. One such disease, Cockayne syndrome (CS), has an incidence of about 2.5 per million births and, in its most severe form, is associated with a life span of less than seven years. Children with Cockayne syndrome show marked signs of premature aging, such as loss of weight, hair, hearing and sight, as well as facial deformation and neurodegeneration.

Cockayne syndrome is caused by mutations in either of two genes involved in the repair of DNA damage induced by ultraviolet (UV) rays. CS patients are hypersensitive to sunlight and burn easily. For decades it was believed that the premature aging process associated with this disease was essentially caused by DNA repair deficiency.

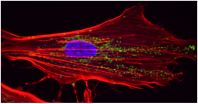

By comparing cells from CS patients and from patients with another, related syndrome causing only UV hypersensitivity, the team led by Miria Ricchetti (Institut Pasteur) with Laurent Chatre (CNRS, at the Institut Pasteur), in collaboration with Alain Sarasin (CNRS, at the Institut Gustave Roussy) and Denis Biard (CEA), discovered that the defects in CS cells are actually due to excessive production of a protease (HTRA3), and induced by oxidative cell stress. In CS cells, HTRA3 degrades a key component of the machinery responsible for DNA replication in mitochondria (the cellular "powerhouses"), thereby affecting mitochondrial activity.

Until now, neurodegeneration and aging have largely been attributed to the damage inflicted on cells by mitochondrial free radicals. The new study shows that free radicals also activate the expression of a protein known as HTRA3, which is particularly damaging to mitochondria. This onslaught on the mitochondrial core is a key factor in the degeneration of cells in patients suffering from premature aging.

By means of two new therapeutic strategies, using an HTRA3 inhibitor or a broad-spectrum antioxidant to capture free radicals, the scientists succeeded in restoring normal levels of this protease. They were accordingly able to restore mitochondrial function in CS patients. This progress both paves the way for new therapeutic approaches, which could soon be tested in patients, and provides new diagnostic tools.

The Institut Pasteur, CNRS, CEA and IGR have filed a patent application for methods of diagnosing and treating premature aging using the protease HTRA3.

These defective mechanisms may also occur, but at a slower rate, in healthy cells, leading to physiological aging. The development of therapeutic strategies targeting premature aging diseases could therefore open new research possibilities in terms of preventive therapies for the pathologies associated with normal aging.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the Institut Pasteur, the French National Research Agency (ANR) and the French Muscular Dystrophy Association (AFM).

Source

Reversal of mitochondrial defects with CSB-dependent serine protease inhibitors in patient cells of the progeroid Cockayne syndrome, PNAS PLUS, May 18, 2015

Laurent Chatre1,2,, Denis Biard3, Alain Sarasin4,5 and Miria Ricchetti1,2,6

1Institut Pasteur, Department of Genomes and Genetics, Yeast Molecular Genetics Unit, 25 Rue du Dr. Roux, 75724, Paris, France,

2CNRS UMR 3525, Team Stability of Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA,

3CEA, DSV, IMETI, SEPIA, Team Cellular Engineering and Human Syndromes, F-92265 Fontenay-aux-Roses, France,

4UMR8200 CNRS Laboratory of Genetic Stability and Oncogenesis, Institut de cancérologie Gustave Roussy, and University Paris-Sud, 114 rue Edouard Vaillant, 94805 Villejuif, France,

5Department of Genetics, Institut de Cancérologie Gustave Roussy.

6Main author.

BOZEMAN, Mont. -- Montana State University researchers and their collaborators have published their findings about a chemical compound that shows potential for treating rheumatoid arthritis.

The paper ran in the June issue of the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (JPET), and one of its illustrations is featured on the cover. JPET is a leading scientific journal that covers all aspects of pharmacology, a field that investigates the effects of drugs on biological systems and vice versa.

"This journal is one of the top journals that reports new types ...

According to small and medium-sized enterprises, sizable social security and other wage-related costs still form the single greatest obstacle for improving productivity. Additionally, a lack of competence among supervisors was also seen as an obstacle for productivity. This information is from a newly published survey by the Lappeenranta University of Technology (LUT), which is a follow-up to a study on the obstacles that restrain the productivity of companies published in 1997. A total of 239 representatives from Finnish small and medium-sized enterprises responded to ...

PHOENIX -- Prior studies have shown that most dog bite injuries result from family dogs. A new study conducted by Mayo Clinic and Phoenix Children's Hospital shed some further light on the nature of these injuries.

The American Veterinary association has designated this week as Dog Bite Prevention Week.

The study, published last month in the Journal of Pediatric Surgery, demonstrated that more than 50 percent of the dog bites injuries treated at Phoenix Children's Hospital came from dogs belonging to an immediate family member.

The retrospective study looked at a ...

The advice, whether from Shakespeare or a modern self-help guru, is common: Be true to yourself. New research suggests that this drive for authenticity -- living in accordance with our sense of self, emotions, and values -- may be so fundamental that we actually feel immoral and impure when we violate our true sense of self. This sense of impurity, in turn, may lead us to engage in cleansing or charitable behaviors as a way of clearing our conscience.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Our work ...

Two words that arouse immediate fear in some people inspire something else altogether in Jennifer Fill.

"I love snakes and fire," Fill says. "When I was looking at grad schools, I thought, 'if I can just combine those two things, I bet I'll be really happy.'"

It's not about cozy campfires or garden-variety garters for Fill, a biologist who recently defended her dissertation at the University of South Carolina. The fires she's interested in are forest fires, and the snake that was the subject of her doctoral studies is Crotalus adamanteus, commonly called the eastern diamondback ...

A new report on New York City's Expanded Success Initiative (ESI), which is designed to boost college and career readiness among Black and Latino male students, finds that the schools involved are changing the way they operate and offering students opportunities they would not otherwise have.

"There is strong evidence that these schools are doing something different as a result of ESI," says the study's lead author, Adriana Villavicencio, senior research associate at the Research Alliance for New York City Schools. "We are seeing important shifts in the tone and culture ...

Bacteria that live in the guts of cicadas have split into many separate but interdependent species in a strange evolutionary phenomenon that leaves them reliant on a bloated genome, a new paper by CIFAR Fellow John McCutcheon's lab (University of Montana) has found.

Cicadas subsist on tree sap, which doesn't provide them all the nutrients they need to live. Bacteria in their gut, including one called Hodgkinia, turns the sap into amino acids that sustain them during their unusual lives. Cicadas spend most of their lives underground before emerging in droves, singing loudly, ...

The sight of skilful aerial manoeuvring by flocks of Greylag geese to avoid collisions with York's Millennium Bridge intrigued mathematical biologist Dr Jamie Wood. It raised the question of how birds collectively negotiate man-made obstacles such as wind turbines which lie in their flight paths.

It led to a research project with colleagues in the Departments of Biology and Mathematics at York and scientists at the Animal and Plant Health Agency. The study found that the social structure of groups of migratory birds may have a significant effect on their vulnerability ...

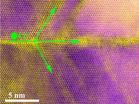

Most people see defects as flaws. A few Michigan Technological University researchers, however, see them as opportunities. Twin boundaries -- which are small, symmetrical defects in materials -- may present an opportunity to improve lithium-ion batteries. The twin boundary defects act as energy highways and could help get better performance out of the batteries.

This finding, published in Nano Letters earlier this year, turns a previously held notion of material defects on its head. Reza Shahbazian-Yassar helped lead the study and holds a joint appointment at Michigan ...

May 21, 2015 -- A technique called auditory brainstem implantation can restore hearing for patients who can't benefit from cochlear implants. A team of US and Japanese experts has mapped out the surgical anatomy and approaches for auditory brainstem implantation in the June issue of Operative Neurosurgery, published on behalf of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons by Wolters Kluwer.

Dr. Albert L. Rhoton, Jr., and colleagues of University of Florida, Gainesville, and Fukuoka University, Japan, performed a series of meticulous dissections to demonstrate and illustrate ...