(Press-News.org) Cat taste receptors respond in a unique way to bitter compounds compared with human receptors, according to research published in the open access journal BMC Neuroscience. The study represents the first glimpse into how domestic cats perceive bitterness in food at a molecular level, and could explain why cats are sometimes such picky eaters.

The ability to detect bitter chemicals is thought to have evolved because of its utility in avoiding toxic compounds often found in plants. All cats, from pets to wild tigers, are carnivores that consume little plant material. Domestic cats, however, may still encounter bitter flavors in food and medicines.

Domestic cats have a reputation of being rather unpredictable in their dietary choices. This could be explained by their perception of bitter, which differs from that of other mammals due to variations in their repertoire of bitter receptors. It is the goal of many pharmaceutical and food manufacturers to identify compounds that either block or alter bitter perception, to create a more palatable product.

The teams at AFB International and Integral Molecular studied the behavior of two different cat bitter taste receptors in cell-based experiments, investigating their responsiveness to bitter compounds, and comparing these to the human versions of these receptors.

TAS2R38 is a bitter taste receptor in humans of which some people have 'supertaster' variants that give them an extreme sensitivity to bitter compounds, explaining some people's strong aversions to broccoli and brussels sprouts.

Compared with the human TAS2R38 receptor, the cat version was tenfold less sensitive to a key bitter compound PTC and did not respond at all to another bitter compound PROP.

Like its human counterpart, the cat bitter taste receptor Tas2r43 was activated by bitter compounds aloin (found in the aloe plant) and denatonium (used to deter children and pets from consuming chemicals such as antifreeze) but responded differently to the compounds. The cat receptor was less sensitive to aloin and more sensitive to denatonium than the human receptor. It also differed from the human taste receptor by being insensitive to saccharin, an artificial sweetener that tends to have a bitter aftertaste in humans.

Co-author Nancy Rawson from AFB International, a pet food flavor company, said: 'We confront the challenge of 'finicky cats' every day. As such, it is exciting to find an unexpected receptor response to bitter compounds that has never been described in the literature to date for any other species. These insights and future discoveries will be invaluable in formulating appealing food for cats, as well as enhancing the acceptability of their medications.'

Co-author Joseph Rucker from Integral Molecular, a biotechnology company, said: 'Feline bitter taste has not been well studied. We applied our experience in studying membrane proteins, such as taste receptors, to enable this first glimpse into how domestic cats perceive bitterness in food at a molecular level. We were surprised to see that one of the cat taste receptors responded to a more limited range of bitter compounds compared to humans, suggesting that cats may be detecting a narrower, or at least a different, repertoire of bitter-tasting compounds.'

The team also found that probenecid, a known inhibitor of human bitter taste receptors, also worked on both cat taste receptors, preventing stimulation when in the presence of PTC, aloin and denatonium.

The team says that these insights and further study could be instrumental in formulating appetizing food for household cats as well as designing masking agents to enhance the acceptability of medications.

INFORMATION:

The authors are employees of Integral Molecular and AFB International. Joseph Rucker is a shareholder of Integral Molecular. These data are part of a patent application filed by AFB International.

Contact:

Joel Winston

Joel.Winston@biomedcentral.com

44-203-192-2081 (office)

44-776-654-0147 (cell)

BioMed Central

Notes to editor:

1. Research article: Michelle M Sandau, Jason R Goodman, Anu Thomas, Joseph B Rucker and Nancy E Rawson

A functional comparison of the domestic cat bitter receptors Tas2r38 and Tas2r43 with their human orthologs

BMC Neuroscience 2015

doi: 10.1186/s128628-015-0170-6

For a copy of the embargoed research article, please contact Joel.Winston@biomedcentral.com

After embargo, article available at journal website here: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s128628-015-0170-6

Please name the journal in any story you write. If you are writing for the web, please link to the article. All articles are available free of charge, according to BioMed Central's open access policy.

2. BMC Neuroscience is an open access, peer-reviewed journal that considers articles on all aspects of the nervous system, including molecular, cellular, developmental and animal model studies, as well as cognitive and behavioral research, and computational modeling.

BMC Neuroscience is part of the BMC series which publishes subject-specific journals focused on the needs of individual research communities across all areas of biology and medicine. We offer an efficient, fair and friendly peer review service, and are committed to publishing all sound science, provided that there is some advance in knowledge presented by the work.

3. BioMed Central is an STM (Science, Technology and Medicine) publisher which has pioneered the open access publishing model. All peer- reviewed research articles published by BioMed Central are made immediately and freely accessible online, and are licensed to allow redistribution and reuse. BioMed Central is part of Springer Science+Business Media, a leading global publisher in the STM sector.

Some athletes who take part in endurance exercise such as marathon running, endurance triathlons or alpine cycling can develop irregularities in their heartbeats that can, occasionally, lead to their sudden death.

Now, new evidence published in the European Heart Journal [1] today (Wednesday) has shown that doctors who try to detect these heartbeat irregularities (known as arrhythmias) by focusing on the left ventricle of the heart, or on the right ventricle while an athlete is resting, will miss important signs of right ventricular dysfunction that can only be detected ...

One of Australia's smallest birds has found a cunning way to protect its nest from predators by crying wolf, or rather hawk, and mimicking the warning calls of other birds.

Researchers from The Australian National University (ANU) found that the tiny brown thornbill mimics the hawk warning call of a variety of birds to scare off predators threatening its nest, such as the larger pied currawong.

"It's not superbly accurate mimicry, but it's enough to fool the predator," said Dr Branislav Igic, who carried out the study during his PhD at ANU Research School of Biology.

"A ...

A group of former senior editors, writing in The BMJ today, criticise a "seriously flawed and inflammatory attack" by The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) on what that journal believes have become overly stringent policies on conflicts of interest.

The NEJM was the first major medical journal to introduce conflict of interest policies in 1984. It required all authors to disclose any financial ties to health industries and made conflict of interests more transparent.

But recently the NEJM published a series of commentaries and an editorial that attempt to justify ...

Bullying in teenage years is strongly associated with depression later on in life, suggests new research published in The BMJ this week.

Depression is a major public health problem with high economic and societal costs. There is a rapid increase in depression from childhood to adulthood and one contributing factor could be bullying by peers. But the link between bullying at school and depression in adulthood is still unclear due to limitations in previous research.

So a team of scientists, led by Lucy Bowes at the University of Oxford, carried out one of the largest ...

There is no strong evidence that the popular smoking cessation drug varenicline is associated with increased risks of suicidal behaviours, criminal offending, transport accidents, traffic-related offences, and psychoses, finds a study in The BMJ this week.

The findings are based on over 69,000 individuals in Sweden who were prescribed varenicline between 2006 and 2009. Previous reports suggesting a link may not have taken full account of underlying risk factors, say the authors.

Varenicline is widely prescribed for the treatment of nicotine dependence, but reports that ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- A long-term study of mother-child pairs in Pakistan has found that the children turn out pretty much the same, whether or not their mothers received treatment for depression during pregnancy.

An earlier study of the same population found that the mothers themselves benefited from the treatment, with less depression, and demonstrating related healthy behaviors with their newborns, such as breastfeeding. But those improvements were short-lived.

The "Thinking Healthy Programme" is a successful depression intervention evaluated through a randomized trial ...

Washington, DC--Relying on the better-functioning side of the body after a stroke can cause brain changes that hinder rehabilitation of the impaired side, according to an animal study published June 3 in the Journal of Neuroscience. Strokes that occur in one brain hemisphere can result in poor motor function on the opposite side of the body, leading to heavy reliance on the "good" side. This study, led by Soo Young Kim and performed at the University of Texas at Austin and the University of California, Berkeley, found that such compensation produces structural brain changes ...

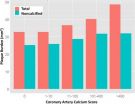

OAK BROOK, Ill. -- Non-calcified arterial plaque is associated with diabetes, high systolic blood pressure and elevated 'bad' cholesterol levels in asymptomatic individuals, according to a new study published online in the journal Radiology.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of death in men and women worldwide, accounting for 17 million deaths annually. Current treatment strategies focus on cardiovascular risk and serum cholesterol levels rather than direct assessment of extent of disease in the coronary arteries.

Plaque that forms in the arterial walls ...

A new study shows that social and sensory overstimulation drives autistic behaviors. The study, conducted on rats exposed to a known risk factor in humans, supports the unconventional view of the autistic brain as hyper-functional, and offers new hope with therapeutic emphasis on paced and non-surprising environments tailored to the individual's sensitivity.

For decades, autism has been viewed as a form of mental retardation, a brain disease that destroys children's ability to learn, feel and empathize, thus leaving them disconnected from our complex and ever-changing ...

You might not need to remember those complicated e-mail and bank account passwords for much longer. According to a new study, the way your brain responds to certain words could be used to replace passwords.

In "Brainprint," a newly published study in academic journal Neurocomputing, researchers from Binghamton University observed the brain signals of 45 volunteers as they read a list of 75 acronyms, such as FBI and DVD. They recorded the brain's reaction to each group of letters, focusing on the part of the brain associated with reading and recognizing words, and found ...