(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (June 4, 2015) - Leveraging a novel system designed to examine the double-strand DNA breaks that occur as a consequence of gene amplification during DNA replication, Whitehead Institute scientists are bringing new clarity to the causes of such genomic damage. Moreover, because errors arising during DNA replication and gene amplification result in chromosomal abnormalities often found in malignant cells, these new findings may bolster our understandings of certain drivers of cancer progression.

At the core of system, developed in the lab of Whitehead Member Terry Orr-Weaver, are Drosophila ovarian follicle cells--a unique cell type whose DNA replication is tightly regulated during organismal development. The controlled nature of replication in these cells enabled Orr-Weaver and her lab to manipulate aspects of the process to discover the sites of double-strand breaks (DSBs), their likely cause, and the mechanisms by which the cells attempt repair. The system is described in the latest edition of Current Biology.

"We know that improper regulation of replication can lead to changes in copy number, and the backdrop is that there are changes in DNA copy number in cancer cells," says Orr-Weaver, who is also an American Cancer Society Research Professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "We know that unregulated replication leads to genome instability, but nobody was able to really look at that in a direct way."

When successful, DNA replication transmits genetic material from mother to daughter cells (as occurs during mitotic cell division) or boosts DNA copy number in the cells of tissues that rely on multiple copies of the genome to increase in size. In the cells studied here, the process of re-replication (also referred to as amplification) originates at six specific sites known as DAFCs (for Drosophila Amplicons in Follicle Cells). Two-pronged structures known as replication forks form at the DAFCs and move along the double-stranded DNA, unwinding it to create two single strands for copying.

Although scientists had surmised that DSBs occur when replication forks--whose movement Orr-Weaver likens to a train moving along a DNA railroad track--collide with each other, none had shown it. Until know. Using a combination of imaging and sequencing technologies, Orr-Weaver and her lab found that DSBs were occurring at the sites of replication forks that had stalled, almost certainly because of collision.

"Because of the resolution of this system, we're now able to know where the forks are in relation to where the breaks are happening," says Jessica Alexander, a graduate student in the Orr-Weaver lab and first author of the Current Biology paper.

Alexander and Orr-Weaver also found that the DSBs must be repaired to maintain fork progression. The way in which the repair occurs, however, proved somewhat surprising. DNA breaks are mended in one of two ways: the first, known as non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) is rapid but prone to mistakes; the second, homologous recombination (HR), takes longer but is much more accurate. Given the importance of faithful replication, one might presume that HR would be the chosen repair method. By altering various checkpoint mechanisms in DNA repair pathways, the researchers found that the cells instead rely on quick-and-dirty NHEJ to fix the DSBs and keep the re-replication forks moving. Speed, it seems is of the essence.

"Non-homologous end-joining is about 14 times faster than homologous recombination," notes Alexander. "The follicle cells don't care about using a mutagenic repair pathway, though, because they slough off the Drosophila oocyte at the end of amplification. Any mutations that arise won't affect the organism."

With this new system in hand, Orr-Weaver and her lab can begin to isolate the individual components involved in the repair pathways, resolve their precise roles, and perhaps determine whether other genomic locations are involved in the process.

"This really provides us with the fundamental knowledge to move forward, looking mechanistically at what the cell uses to repair the breaks," she says. "It's possible that where this happens in the genome could affect the way the DNA gets repaired."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant GM57940) and the MIT School of Science Fellowship in Cancer Research.

Terry Orr-Weaver's primary affiliation is with Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, where her laboratory is located and all her research is conducted. She is also an American Cancer Society Research Professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Full Citation:

"Replication fork progression during re-replication requires the DNA damage checkpoint and double-strand break repair"

Current Biology, June 4, 2015

Jessica L. Alexander (1,2), M. Inmaculada Barrasa (1), Terry L. Orr-Weaver (1,2)

1. Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Nine Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

2. Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

About 10 years ago, Peter Hews stumbled across some bones sticking out of a cliff along the Oldman River in southeastern Alberta, Canada. Now, scientists describe in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on June 4 that those bones belonged to a nearly intact skull of a very unusual horned dinosaur--a close relative of the familiar Triceratops that had been unknown to science until now.

"The specimen comes from a geographic region of Alberta where we have not found horned dinosaurs before, so from the onset we knew it was important," says Dr. Caleb Brown of the Royal ...

Infectious diseases kill more people worldwide than any other single cause, but treatment often fails because a small fraction of bacterial cells can transiently survive antibiotics and recolonize the body. A study published June 4 in Molecular Cell reveals that these so-called persisters form in response to adverse conditions through the action of a molecule called Obg, which plays an important role in all major cellular processes in multiple bacterial species. By revealing a shared genetic mechanism underlying bacterial persistence, the study paves the way for novel diagnostic ...

A team of researchers led by the University of Cambridge has described for the first time in humans how the epigenome - the suite of molecules attached to our DNA that switch our genes on and off - is comprehensively erased in early primordial germ cells prior to the generation of egg and sperm. However, the study, published today in the journal Cell, shows some regions of our DNA - including those associated with conditions such as obesity and schizophrenia - resist complete reprogramming.

Although our genetic information - the 'code of life' - is written in our DNA, ...

Our social connections and social compass define us to a large degree as human. Indeed, our tendency to act to benefit others without benefit to ourselves is regarded by some as the epitome of human nature and culture. But is it truly a quality unique to humans, or is this apparent virtue common to other species such as rats?

"We would not hesitate about helping an older person trying to cross the road", says Dr. Cristina Márquez, who conducted this study with Scott Rennie and Diana Costa from the Behavioural Neuroscience Lab, led by Dr. Marta Moita. "This type of ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The process that allows our brains to learn and generate new memories also leads to degeneration as we age, according to a new study by researchers at MIT.

The finding, reported in a paper published today in the journal Cell, could ultimately help researchers develop new approaches to preventing cognitive decline in disorders such as Alzheimer's disease.

Each time we learn something new, our brain cells break their DNA, creating damage that the neurons must immediately repair, according to Li-Huei Tsai, the Picower Professor of Neuroscience and director ...

SEATTLE - Eating less late at night may help curb the concentration and alertness deficits that accompany sleep deprivation, according to results of a new study from researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania that will be presented at SLEEP 2015, the 29th annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC.

"Adults consume approximately 500 additional calories during late-night hours when they are sleep restricted," said the study's senior author David F. Dinges, PhD, director of the Unit for Experimental Psychiatry ...

Medicare costs for older patients with oral cavity and pharyngeal cancers increased based on demographics, co-existing illnesses and treatment selection, according to a report published online by JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery.

Many cases of oral cavity cancer and most cases of pharyngeal cancer are diagnosed at advanced stages when management of the disease is complex and treatment is aggressive and involves multiple specialists. The publicly funded Medicare program provides an opportunity for researchers to estimate the cost of care for older patients with ...

Placenta doesn't prevent postpartum depression, ease pain, boost energy or aid lactation

Celebrities spike trend, but no studies show human benefits

Unknown risks to women and babies

CHICAGO -- Celebrities such as Kourtney Kardashian blogged and raved about the benefits of their personal placenta 'vitamins' and spiked women's interest in the practice of consuming their placentas after childbirth.

But a new Northwestern Medicine review of 10 current published research studies on placentophagy did not turn up any human or animal data to support the common ...

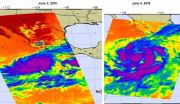

One of the instruments that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite looks at tropical cyclones using infrared light. In a comparison of infrared data from June 3 and 4, images show that Hurricane Blanca had weakened and became less organized.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite measured cloud top temperatures in Blanca on June 3 at 20:17 UTC (4:23 p.m. EDT) when maximum sustained winds were near 140 mph (220 kph) with higher gusts. At the time, Blanca was a category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. ...

DURHAM, NC -- There aren't any giants or midgets when it comes to the cells in your body, and now Duke University scientists think they know why.

A new study appearing June 3 in Nature shows that a cell's initial size determines how much it will grow before it splits into two.

This finding goes against recent publications suggesting cells always add the same amount of mass, with some random fluctuations, before beginning division.

"It's like students going through college," said Lingchong You, the Paul Ruffin Scarborough Associate Professor of Engineering in the ...