(Press-News.org) Anti-cancer strategies generally involve killing off tumor cells. However, cancer cells may instead be coaxed to turn back into normal tissue simply by reactivating a single gene, according to a study published June 18th in the journal Cell. Researchers found that restoring normal levels of a human colorectal cancer gene in mice stopped tumor growth and re-established normal intestinal function within only 4 days. Remarkably, tumors were eliminated within 2 weeks, and signs of cancer were prevented months later. The findings provide proof of principle that restoring the function of a single tumor suppressor gene can cause tumor regression and suggest future avenues for developing effective cancer treatments.

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in developed countries, accounting for nearly 700,000 deaths worldwide each year. "Treatment regimes for advanced colorectal cancer involve combination chemotherapies that are toxic and largely ineffective, yet have remained the backbone of therapy over the last decade," says senior study author Scott Lowe of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Up to 90% of colorectal tumors contain inactivating mutations in a tumor suppressor gene called adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc). Although these mutations are thought to initiate colorectal cancer, it has not been clear whether Apc inactivation also plays a role in tumor growth and survival once cancer has already developed.

"We wanted to know whether correcting the disruption of Apc in established cancers would be enough to stop tumor growth and induce regression," says first author Lukas Dow of Weill Cornell Medical College. This question has been challenging to address experimentally because attempts to restore function to lost or mutated genes in cancer cells often trigger excess gene activity, causing other problems in normal cells.

To overcome this challenge, Lowe and his team used a genetic technique to precisely and reversibly disrupt Apc activity in a novel mouse model of colorectal cancer. While the vast majority of existing animal models of colorectal cancer develop tumors primarily in the small intestine, the new animal model also developed tumors in the colon, similar to patients. Consistent with previous findings, Apc suppression in the animals activated the Wnt signaling pathway, which is known to control cell proliferation, migration, and survival.

When Apc was reactivated, Wnt signaling returned to normal levels, tumor cells stopped proliferating, and intestinal cells recovered normal function. Tumors regressed and disappeared or reintegrated into normal tissue within 2 weeks, and there were no signs of cancer relapse over a 6-month follow-up period. Moreover, this approach was effective in treating mice with malignant colorectal cancer tumors containing Kras and p53 mutations, which are found in about half of colorectal tumors in humans.

Although Apc reactivation is unlikely to be relevant to other types of cancer, the general experimental approach could have broad implications. "The concept of identifying tumor-specific driving mutations is a major focus of many laboratories around the world," Dow says. "If we can define which types of mutations and changes are the critical events driving tumor growth, we will be better equipped to identify the most appropriate treatments for individual cancers."

For their own part, Lowe and his team will next examine the consequences of Apc reactivation in tumors that progress beyond local invasion to produce distant metastases. They will also continue to investigate why Apc is so effective at suppressing colon tumor growth, with the goal of one day mimicking this effect with drug treatments.

"It is currently impractical to directly restore Apc function in patients with colorectal cancer, and past evidence suggests that completely blocking Wnt signaling would likely be severely toxic to normal intestinal cells," Lowe says. "However, our findings suggest that small molecules aimed at modulating, but not blocking, the Wnt pathway might achieve similar effects to Apc reactivation. Further work will be critical to determine whether WNT inhibition or similar approaches would provide long-term therapeutic value in the clinic."

INFORMATION:

Cell, Dow et al.: "Apc restoration promotes cellular differentiation and reestablishes crypt homeostasis in colorectal cancer."

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.033

Cell, the flagship journal of Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that publishes findings of unusual significance in any area of experimental biology, including but not limited to cell biology, molecular biology, neuroscience, immunology, virology and microbiology, cancer, human genetics, systems biology, signaling, and disease mechanisms and therapeutics. For more information, please visit http://www.cell.com/cell. To receive media alerts for Cell or other Cell Press journals, contact press@cell.com.

American scientists have discovered that a drug commonly used to treat osteoporosis in humans also stimulates the production of cells that control insulin balance in diabetic mice. While other compounds have been shown to have this effect, the drug (Denosumab) is already FDA approved and could more quickly move to clinical trials as a diabetes treatment. The research is published June 18 in Cell Metabolism.

Diabetes is a major health issue worldwide that arises due to a deficiency of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. In type 1 diabetes, beta cells die from ...

Cutaneous melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer, is now believed to be divided into four distinct genomic subtypes, say researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, a finding that could prove valuable in the ever-increasing pursuit of personalized medicine.

As part of The Cancer Genome Atlas, researchers identified four melanoma subtypes: BRAF, RAS, NF1 and Triple-WT, which were defined by presence or absence of mutations from analysis of samples obtained from 331 patients. The five-year study resulted from an international collaboration of ...

PHILADELPHIA -- Most of us need seven to eight hours of sleep a night to function well, but some people seem to need a lot less sleep. The difference is largely due to genetic variability. In research published online June 18th in Current Biology, researchers report that two genes, originally known for their regulation of cell division, are required for normal slumber in fly models of sleep: taranis and Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1).

'There's a lot we don't understand about sleep, especially when it comes to the protein machinery that initiates the process on the ...

In 2012, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine showed that heart muscle cells made from the skin of people with a cardiac condition called dilated cardiomyopathy beat with less force than those made from the skin of healthy people. These cells also responded less readily to the waves of calcium that control the timing and strength of each contraction.

Now, the same research team has teased apart the molecular basis for these differences and identified a drug treatment that at least partially restores function to diseased cells grown in a laboratory ...

Adult neural stem cells, which are commonly thought of as having the ability to develop into many type of brain cells, are in reality pre-programmed before birth to make very specific types of neurons, at least in mice, according to a study led by UC San Francisco researchers.

"This work fundamentally changes the way we think about stem cells," said principal investigator Arturo Alvarez-Buylla, UCSF professor of neurological surgery, Heather and Melanie Muss Endowed Chair and a principal investigator in the UCSF Brain Tumor Research Center and the Eli and Edythe Broad ...

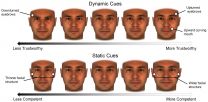

We can alter our facial features in ways that make us look more trustworthy, but don't have the same ability to appear more competent, a team of New York University psychology researchers has found.

The study, which appears in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, a SAGE journal, points to both the limits and potential we have in visually representing ourselves--from dating and career-networking sites to social media posts.

"Our findings show that facial cues conveying trustworthiness are malleable while facial cues conveying competence and ability are significantly ...

Want to lose abdominal fat, get smarter and live longer? New research led by USC's Valter Longo shows that periodically adopting a diet that mimics the effects of fasting may yield a wide range of health benefits.

In a new study, Longo and his colleagues show that cycles of a four-day low-calorie diet that mimics fasting (FMD) cut visceral belly fat and elevated the number of progenitor and stem cells in several organs of old mice -- including the brain, where it boosted neural regeneration and improved learning and memory.

The mouse tests were part of a three-tiered ...

Last June, in the early days of the Ebola outbreak in Western Africa, a team of researchers sequenced the genome of the deadly virus at unprecedented scale and speed. Their findings revealed a number of critical facts as the outbreak was unfolding, including that the virus was being transmitted only by person-to-person contact and that it was picking up new mutations through its many transmissions.

While public health officials now believe the worst of the epidemic is behind us, it is not yet over, and questions raised by the previous work still await answers.

To ...

PHILADELPHIA - Several well-known neurodegenerative diseases, such as Lou Gehrig's (ALS), Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Huntington's disease, all result in part from a defect in autophagy - one way a cell removes and recycles misfolded proteins and pathogens. In a paper published this week in Current Biology, postdoctoral fellow David Kast, PhD, and professor Roberto Dominguez, PhD, and three other colleagues from the Department of Physiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, show for the first time that the formation of ephemeral compartments ...

University of California San Francisco scientists have identified characteristics of a family of daughter cells, called MPPs, which are the first to arise from stem cells within bone marrow that generate the entire blood system. The researchers said the discovery raises the possibility that, by manipulating the fates of MPPs or parent stem cells, medical researchers could one day help overcome imbalances and deficiencies that can arise in the blood system due to aging or in patients with specific types of leukemia.

Similar imbalances can render patients vulnerable immediately ...