(Press-News.org) (Philadelphia, PA) - In a life-threatening situation, the heart beats faster and harder, invigorated by the fight-or-flight response, which instantaneously prepares a person to react or run. Now, a new study by researchers at Temple University School of Medicine (TUSM) shows that the uptick in heart muscle contractility that occurs under acute stress is driven by a flood of calcium into mitochondria--the cells' energy-producing powerhouses.

Researchers have long known that calcium enters mitochondria in heart muscle cells, but the physiological role of that process was unclear. "The function of mitochondrial calcium uptake during stress generally was linked to the collapse of energy production and cell death," explained John W. Elrod, PhD, Assistant Professor of Pharmacology and at the Center for Translational Medicine at TUSM, and senior investigator on the new study, which appears June 25 in the journal Cell Reports.

"We show, however, that in periods of acute stress, increased calcium uptake by mitochondria in the heart functions in ways that are good and bad: during the fight-or-flight response, it provides the necessary energetic support for the heart, but during a heart attack, it leads to the death of large numbers of heart cells," Dr. Elrod said.

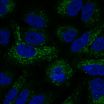

In the fight-or-flight response, the release of adrenaline activates numerous systems in the body to prepare for the perceived stress. A key aspect of this response is an increase in cardiac contractility. Adrenaline increases calcium cycling in the heart to drive contraction. That same calcium enters mitochondria through a channel known as the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU). Dr. Elrod and colleagues at TUSM and Cincinnati Children's Hospital have been investigating MCU since its discovery in 2011, attempting to elucidate its function specifically in heart muscle cells.

As part of their work, they knocked out, or removed, MCU from mitochondria in the hearts of adult mice. In doing so, they discovered that in mice lacking MCU, the heart failed to respond to adrenaline-receptor stimulation with isoproterenol--an adrenaline-like chemical that in high doses normally sends the heart into overdrive, mimicking aspects of the fight-or-flight response. Meanwhile, in mice lacking MCU that suffered heart attacks with ischemia (blockage of blood flow) followed by reperfusion (the restoration of blood and oxygen supply), the loss of MCU was found to preserve heart tissue and increase cell survival. Without the channel, calcium was unable to enter mitochondria to trigger cell death.

"The effects were specific to acute stress," Dr. Elrod explained. "Under normal conditions, the loss of MCU appeared to have little to no impact on metabolic function in the heart."

The new findings complement work that is ongoing by researchers at Temple to better understand heart function and adrenergic (adrenaline-related) signaling in heart cells. In 2013, Madesh Muniswamy, PhD, Associate Professor of Biochemistry, Associate Professor at the Cardiovascular Research Center and Associate Professor at the Center for Translational Medicine at TUSM and a coauthor with Dr. Elrod on the new study, reported the discovery of MCUR1, a protein in the inner membrane of the mitochondrion that is essential to MCU-mediated calcium uptake.

Dr. Elrod and colleagues plan to continue their investigations of MCU by next looking at its role in chronic stress, which is relevant to conditions such as heart failure and high blood pressure.

"We are also exploring other calcium handling pathways in heart cells and particularly how calcium escapes from mitochondria," Dr. Elrod noted. "Understanding how calcium exchange at the mitochondria is regulated may help target new therapies to preserve energy production in the cell but limit the calcium overload associated with cellular demise."

INFORMATION:

Other researchers contributing to the work at Temple include Timothy S. Luongo, Jonathan P. Lambert, Ancai Yuan, Xueqian Zhang, Jianliang Song, Santhanam Shanmughapriya, Erhe Gao, Walter J. Koch, and Joseph Y. Cheung, at the Center for Translational Medicine and Polina Gross and Steven R. Houser at TUSM's Cardiovascular Research Center.

The research was supported by grants to Dr. Elrod from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health (R01 HL123966-01) and the American Heart Association (14SDG18910041).

About Temple Health

Temple University Health System (TUHS) is a $1.8 billion academic health system dedicated to providing access to quality patient care and supporting excellence in medical education and research. The Health System consists of Temple University Hospital (TUH), ranked among the "Best Hospitals" in the region by U.S. News & World Report; TUH-Episcopal Campus; TUH-Northeastern Campus; Fox Chase Cancer Center, an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center; Jeanes Hospital, a community-based hospital offering medical, surgical and emergency services; Temple Transport Team, a ground and air-ambulance company; and Temple Physicians, Inc., a network of community-based specialty and primary-care physician practices. TUHS is affiliated with Temple University School of Medicine.

Temple University School of Medicine (TUSM), established in 1901, is one of the nation's leading medical schools. Each year, the School of Medicine educates approximately 840 medical students and 140 graduate students. Based on its level of funding from the National Institutes of Health, Temple University School of Medicine is the second-highest ranked medical school in Philadelphia and the third-highest in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. According to U.S. News & World Report, TUSM is among the top 10 most applied-to medical schools in the nation.

Temple Health refers to the health, education and research activities carried out by the affiliates of Temple University Health System (TUHS) and by Temple University School of Medicine. TUHS neither provides nor controls the provision of health care. All health care is provided by its member organizations or independent health care providers affiliated with TUHS member organizations. Each TUHS member organization is owned and operated pursuant to its governing documents.

When neurons become active, they call for an extra boost of oxygenated blood -- this change in the presence of blood in different regions of the brain is the basis for functional brain scans. However, what controls this increase or decrease in blood supply has been a long-standing debate.

In a paper published on June 25 in Neuron, Yale University scientists present the strongest evidence yet that smooth muscle cells surrounding blood vessels in the brain are the only cells capable of contracting to control blood vessel diameter and thus regulate blood flow. This basic ...

Think the nest of cables under your desk is bad? Try keeping the trillions of connections crisscrossing your brain organized and free of tangles. A new study coauthored by researchers at UC San Francisco and the Freie Universität Berlin reveals this seemingly intractable job may be simpler than it appears.

The researchers used high-resolution time-lapse imaging of the developing brains of pupal fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) paired with mathematical simulations to unravel a trick of neural wiring that had stumped neuroscientists for decades. They discovered ...

Adult fruit flies given a cancer drug live 12% longer than average, according to a UCL-led study researching healthy ageing. The drug targets a specific cellular process that occurs in animals, including humans, delaying the onset of age-related deaths by slowing the ageing process.

The study published today in Cell and funded by the Max Planck Society and Wellcome Trust shows for the first time that a small molecule drug, which limits the effects of a protein called Ras, can delay the ageing process in animals. The treated fruit flies outlived the control group by staying ...

Boston, MA -- A new study led by researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health finds that a malaria parasite protein called calcineurin is essential for parasite invasion into red blood cells. Human calcineurin is already a proven target for drugs treating other illnesses including adult rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, and the new findings suggest that parasite calcineurin should be a focus for the development of new antimalarial drugs.

"Our study has great biological and medical significance, particularly in light of the huge disease burden of malaria," said ...

LA JOLLA--As a tumor grows, its cancerous cells ramp up an energy-harvesting process to support its hasty development. This process, called autophagy, is normally used by a cell to recycle damaged organelles and proteins, but is also co-opted by cancer cells to meet their increased energy and metabolic demands.

Salk Institute and Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP) scientists have developed a drug that prevents this process from starting in cancer cells. Published June 25, 2015 in Molecular Cell, the new study identifies a small molecule drug that ...

Washington, DC (June 25, 2015) - Comment sections on websites continue to be an environment for trolls to spew racist opinions. The impact of these hateful words shouldn't have an impact on how one views the news or others, but that may not be the case. A recent study published in the journal Human Communication Research, by researchers at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, found exposure to prejudiced online comments can increase people's own prejudice, and increase the likelihood that they leave prejudiced comments themselves.

Mark Hsueh, Kumar Yogeeswaran, ...

June 25 -- During the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, U.S. combat support hospitals treated at least 650 children with severe, combat-related head injuries, according to a special article in the July issue of Neurosurgery, official journal of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. The journal is published by Wolters Kluwer.

"Given the challenging environment and limited available resources, coalition forces were able to provide quality, timely, and life-saving care to many children" with severe head injuries, write Dr. Paul Klimo, Jr., of Semmes-Murphy Neurologic & Spine ...

A large number of patients use online communication tools such as email and Facebook to engage with their physicians, despite recommendations from some hospitals and professional organizations that clinicians limit email contact with patients and avoid "friending" patients on social media, new research suggests.

The findings from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers suggest a disconnect between what patients expect and what physicians -- concerned about confidentiality and being overwhelmed in off-hours -- are willing to do when it comes to online ...

June 25, 2015 - New results in animals highlight a major safety concern regarding a class of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents used in millions of patients each year, according to a paper published online by the journal Investigative Radiology. The journal is published by Wolters Kluwer.

The study adds to concerns that repeated use of specific "linear"-type gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) lead to deposits of the heavy-metal element gadolinium in the brain. The results will have a major impact on the multimillion-dollar market for MRI contrast agents, ...

Many patients in the latter stage of Parkinson's disease are at high risk of dangerous, sometimes fatal, falls. One major reason is the disabling symptom referred to as Freezing of Gait (FoG) -- brief episodes of an inability to step forward that typically occurs during gait initiation or when turning while walking. Patients who experience FoG often lose their independence, which has a direct effect on their already degenerating quality of life. In the absence of effective pharmacological therapies for FoG, technology-based solutions to alleviate the symptom and prolong ...