(Press-News.org) Autopsies of nearly every patient with the lethal neurodegenerative disorder amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and many with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), show pathologists telltale clumps of a protein called TDP-43. Now, working with mouse and human cells, Johns Hopkins researchers report they have discovered the normal role of TDP-43 in cells and why its abnormal accumulation may cause disease.

In an article published Aug. 7 in Science, the researchers say TDP-43 is normally responsible for keeping unwanted stretches of the genetic material RNA, called cryptic exons, from being used by nerve cells to make proteins. When TDP-43 bunches up inside those cells, it malfunctions, lifting the brakes on cryptic exons and causing a cascade of events that kills brain or spinal cord cells. "TDP-43's role in both healthy and diseased cells has long been a mystery, and we hope that solving it will open new pathways toward preventing and treating ALS and FTD," says Philip Wong, Ph.D., a professor of pathology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and senior author of the study.

Almost a decade ago, Wong says, scientists first described the clumps of TDP-43 that commonly appear in the degenerated brain or nerve cells of those with FTD or ALS. But whether the clumps were a cause or an effect of the diseases, and exactly what they did, was unknown.

"Some people thought that the aggregates themselves were toxic," says Jonathan Ling, a graduate student in Wong's lab and first author of the new paper. "Another theory is that the aggregates were just preventing TDP-43 from doing what it should be doing, and that was the problem."

To figure out which theory might be right, Ling deleted the gene for TDP-43 from both lab-grown mouse and human cells and detected abnormal processing of strands of RNA, genetic material responsible for coding and decoding DNA blueprint instructions for making proteins. Specifically, they found that cryptic exons -- segments of RNA usually blocked by cells from becoming part of the final RNA used to make a protein -- were in fact working as blueprints. With the cryptic exons included rather than blocked, proteins involved in key processes in the studied cells were abnormal.

When the researchers studied brain autopsies from patients with ALS and FTD, they confirmed that not only were there buildups of TDP-43, but also cryptic exons in the degenerated brain cells.

In the brains of healthy people, however, they saw no cryptic exons. This finding, the investigators say, suggests that when TDP-43 is clumped together, it no longer works, causing cells to function abnormally as though there's no TDP-43 at all.

TDP-43 only recognizes one particular class of cryptic exon, but other proteins can block many types of exons, so Ling and Wong next tested what would happen when they added one of these blocking proteins to directly target cryptic exons in cells missing TDP-43. Indeed, adding this protein allowed cells to block cryptic exons and remain disease-free.

"What's thought provoking is that we may soon be able to fix this in patients who have lots of accumulated TDP-43," says Ling.

Ling cautions that questions remain about the role of TDP-43 in ALS and FTD. "We've explained what happens after TDP-43 is lost, but we still don't know why it aggregates in the first place," he says. Wong's group is planning studies that may answer these questions, as well as additional tests on how to treat TDP-43 pathology in humans.

The ALS Association estimates that as many as 30,000 Americans are living with ALS at any given time, and more than 5,000 people are newly diagnosed each year. There is no cure for the disease, and most people live two to five years after diagnosis. Similarly, FTD -- thought to affect around 50,000 people in the U.S. -- has no treatment and shortens life span.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on this study are Juan C. Troncoso and Olga Pletnikova from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

For more than 20 years, Caltech geologist Jean-Philippe Avouac has collaborated with the Department of Mines and Geology of Nepal to study the Himalayas--the most active, above-water mountain range on Earth--to learn more about the processes that build mountains and trigger earthquakes. Over that period, he and his colleagues have installed a network of GPS stations in Nepal that allows them to monitor the way Earth's crust moves during and in between earthquakes. So when he heard on April 25 that a magnitude 7.8 earthquake had struck near Gorkha, Nepal, not far from Kathmandu, ...

Case Western Reserve scientists may have uncovered a molecular mechanism that sets into motion dangerous infection in the feet and hands often occurring with uncontrolled diabetes. It appears that high blood sugar unleashes destructive molecules that interfere with the body's natural infection-control defenses.

The harmful molecules -- dicarbonyls -- are breakdown products of glucose that interfere with infection-controlling antimicrobial peptides known as beta-defensins. The Case Western Reserve team discovered how two dicarbonyls -- methylglyoxal (MGO) and glyoxal (GO) ...

ROSEMONT, Ill.--According to a new study in the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (JAAOS), imaging studies necessary to diagnose traumatic injuries sustained by pregnant women are safe when used properly.

During pregnancy, approximately 5 to 8 percent of women sustain traumatic injuries, including fractures and muscle tears. To help evaluate and manage these injuries, orthopaedic surgeons often recommend radiographs and other imaging studies. "While care should be taken to protect the fetus from exposure, most diagnostic studies are generally safe, ...

Women experience more emotional pain following a breakup, but they also more fully recover, according to new research from Binghamton University.

Researchers from Binghamton University and University College London asked 5,705 participants in 96 countries to rate the emotional and physical pain of a breakup on a scale of one (none) to 10 (unbearable). They found that women tend to be more negatively affected by breakups, reporting higher levels of both physical and emotional pain. Women averaged 6.84 in terms of emotional anguish versus 6.58 in men. In terms of physical ...

PITTSBURGH-- In the era of launching Kickstarter campaigns to pay for just about anything, Carnegie Mellon University ethicists warn that the trend of patients funding their own clinical trials may do more harm than good.

CMU's Danielle Wenner and Alex John London and McGill University's Jonathan Kimmelman co-wrote a column in Cell Stem Cell outlining how patient-funded trials may seem like a beneficial new way to involve more patients in research and establish new funding opportunities, but instead they threaten scientific rigor, relevance, efficiency and fairness.

"Patient-funded ...

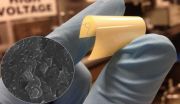

Easily manufactured, low cost, lightweight, flexible dielectric polymers that can operate at high temperatures may be the solution to energy storage and power conversion in electric vehicles and other high temperature applications, according to a team of Penn State engineers.

"Ceramics are usually the choice for energy storage dielectrics for high temperature applications, but they are heavy, weight is a consideration and they are often also brittle," said Qing Wang, professor of materials science and engineering, Penn State. "Polymers have a low working temperature and ...

Researchers at USC have developed a yeast model to study a gene mutation that disrupts the duplication of DNA, causing massive damage to a cell's chromosomes, while somehow allowing the cell to continue dividing.

The result is a mess: Zombie cells that by all rights shouldn't be able to survive, let alone divide, with their chromosomes shattered and strung out between tiny micronuclei. Sometimes they're connected to each other by ultrafine DNA bridges. (Imagine tearing apart a hot pizza - these DNA bridges are like strings of cheese still draping between the separated ...

WASHINGTON - The Society for Public Health Education (SOPHE) announces the publication of a Health Education & Behavior theme section devoted to the latest research on domestic violence prevention and the effectiveness of community coalitions in 19 states to prevent and reduce intimate partner violence. The theme section "DELTA PREP" (Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Alliances and Preparing and Raising Expectations for Prevention) presents findings from a multi-site project supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ...

Abusive men put female partners at greater sexual risk, study finds

Abusive and controlling men are more likely to put their female partners at sexual risk, and the level of that risk escalates along with the abusive behavior, a UW study found.

Published in the Journal of Sex Research in July, the study looked at patterns of risky sexual behavior among heterosexual men aged 18 to 25, including some who self-reported using abusive and/or controlling behaviors in their relationships and others who didn't.

The research found that men who were physically and sexually ...

A critical immune organ called the thymus shrinks rapidly with age, putting older individuals at greater risk for life-threatening infections. A study published August 6 in Cell Reports reveals that thymus atrophy may stem from a decline in its ability to protect against DNA damage from free radicals. The damage accelerates metabolic dysfunction in the organ, progressively reducing its production of pathogen-fighting T cells.

The findings suggest that common dietary antioxidants may slow thymus atrophy and could represent a promising treatment strategy for protecting ...