Bacteria harm the body by releasing toxins - proteins that are exceptionally effective poisons. Always targeting essential molecules, toxins typically go after molecules that are either scarce or whose role is to send important signals. In both cases, only a small number of toxins is required to cause damage.

In contrast, some toxins appear to deviate from these strategies by targeting highly abundant proteins.

A new study shows that one toxin linked to cholera and other diseases, which hones in on a popular and plentiful protein target, also disables a scarce molecule - but in a deceptive way. The toxin turns the common protein into poison against the other essential and much less-abundant protein in a process that renders the immune cell useless.

It's important to understand how toxins work because they are key to enabling bacteria to cause disease. With some of the most lethal toxins - those released by the bacteria that cause whooping cough and dysentery, for example - a single molecule of toxin can kill an entire cell.

"It appears that this toxin followed some of the most sophisticated battlefield strategies long before they were invented by humans: It recognizes that to win the war, one doesn't need to kill all the soldiers. All that is needed is to send in a spy to recruit a few soldiers who will betray their own army and neutralize the officers," said Dmitri Kudryashov, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at The Ohio State University and senior author of the study.

"This finding suggests that with other toxins that appear to act on highly abundant structures, it's likely that we don't actually know how they work."

The research is published in the July 31, 2015, issue of the journal Science.

In this case, the soldiers are the protein actin, which is produced in abundance by almost all human cells and is a very important player in the body's response to an infectious disease. In particular, actin is a molecular motor that enables immune cells to chase and eat invading bacteria. Being present in large concentrations, it is easy for invaders to find.

"For all of these reasons, actin is a common target for many bacterial toxins," Kudryashov said.

One toxin known to have a particular affinity for actin is ACD (actin cross-linking domain). This toxin is released by different bacteria, including those that cause life-threatening conditions: cholera (Vibrio cholera), septicemia or gastroenteritis from eating infected raw oysters (Vibrio vulnificus) and gastric illnesses that threaten people with weakened immune systems (Aeromonas hydrophila).

Previous research had shown that ACD chains together several actin molecules in a way that depletes their ability to properly function, restricting how the immune cells neutralize bacteria. But Kudryashov and colleagues noted that a significant amount of the toxin would be needed to achieve this result.

Bacterial toxins are incredibly efficient killers for a good reason, he said. The human immune system is usually successful in fighting invaders by killing bacteria and neutralizing toxins, meaning bacteria often are not given a chance to produce and deliver much of a toxin to its target cells.

Because bacteria are shrewd about hijacking the immune system, and knowing that a single molecule of the most deadly bacterial toxins can kill a cell, the researchers suspected a smaller amount of the ACD toxin might disable cells by targeting something less common than actin itself.

In an exercise assuming that actin is the primary target, the researchers estimated that a single molecule of ACD introduced to a typical animal cell would take six months to disable half of the actin in the cell - suggesting either actin isn't the actual target or this toxin isn't effective in small doses.

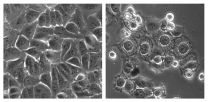

In cultures using intestinal-lining cells, the scientists found that the toxin poisoned the cells while only a small amount of actin was affected. That kind of power raised new questions about how ACD works.

Actin is present in cells in two different forms: a monomer, or a single molecule, and a filament, which is a strand of those molecules strung together. Timely assembly and disassembly of these strands is key to how actin enables immune cells to chase and eat bacteria.

ACD creates a chemical reaction that binds single molecules of actin together in an irregular cluster called an oligomer. These oligomers can't be used to create the strands of actin because their new shapes don't allow them to fit together anymore.

"Essentially, ACD makes actin poisonous against its binding partners," Kudryashov said.

This is where a more precise target becomes apparent. A protein called formin has a specific job to assemble the actin filaments. Once ACD forms the actin oligomers, these oligomers bind to formin much more tightly than a single actin molecule, blocking formin's activity.

"Therefore, ACD effectively hijacks formin by converting actin molecules into new potent poisons," said co-corresponding author Elena Kudryashova, a research scientist in chemistry and biochemistry at Ohio State.

Being blocked by oligomers, formin cannot assist in the assembly of actin strands. When these strands of actin aren't produced, the cell can't function properly anymore.

The researchers confirmed the effect of ACD on formin in a variety of experiments.

"What we see is that very low concentrations of this toxin poison formin very efficiently," said first author David Heisler, a graduate student in the Ohio State Biochemistry Program. "This establishes an entirely new toxicity mechanism."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by an American Heart Association Innovative Research Grant, the National Institutes of Health and Ohio State University start-up funds.

Co-authors include Dmitry Grinevich of Ohio State's Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry; Cristian Suarez, Jonathan Winkelman, David Kovar and Konstantin Birukov of the University of Chicago; Sainath Kotha and Narasimham Parinandi of Ohio State's Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute; and Dimitrios Vavlyonis of Lehigh University.

Contact: Dmitri Kudryashov, 614-292-4848; Kudryashov.1@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, 614-292-8152; Caldwell.151@osu.edu