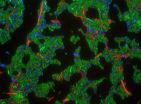

(Press-News.org) Cells continually form membrane vesicles that are released into the cell. If this vital process is disturbed, nerve cells, for example, cannot communicate with each other. The protein molecule dynamin is essential for the regulated formation and release of many vesicles. Scientists of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) and the Institute for Biophysical Chemistry of Hannover Medical School (MHH), together with researchers from the Freie Universität Berlin and the Leibniz-Institut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP), have now elucidated the regulated process by which the molecular "motor" dynamin assembles into a screw-like structure. Moreover, they demonstrated how specific mutations impair the function of dynamin, for example in the congenital muscle disorder centronuclear myopathy or the neuropathy Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (Nature, doi:10.1038/nature14880)**. The researchers' study represents an important contribution to the development of new therapeutic approaches.

To transmit signals, nerve cells release neurotransmitters that are packed in vesicles. These vesicles are formed through membrane invaginations of the cell wall which are constricted and severed by dynamin. First, a chain of dynamin molecules wraps around the neck of the budding vesicle in a spiral. In a second energy-dependent step, the dynamin spiral is constricted, and the vesicle is released into the cell.

The researchers elucidated the 3-dimensional structure of the basic component of the spiral. It consists of four dynamin molecules, called a dynamin tetramer. "For the first time we could determine how the dynamin tetramers assemble into a spiral," said Dr. Katja Fälber from the Crystallography Department of the MDC. "The structure also explains why this process only occurs on membranes: Only there do rearrangements in the dynamin tetramer take place that release the contacts for spiral formation," said Professor Oliver Daumke.

INFORMATION:

**Crystal structure of the dynamin tetramer

Thomas F. Reubold1*, Katja Faelber2*, Nuria Plattner3§, York Posor4§, Katharina Branz4, Ute Curth1,5, Jeanette Schlegel2, Roopsee Anand1, Dietmar J. Manstein1,5, Frank Noé3, Volker Haucke4,6, Oliver Daumke2,6 & Susanne Eschenburg1

1Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Institut für Biophysikalische Chemie, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany

2Max-Delbrück-Centrum für Molekulare Medizin, Kristallographie, Robert-Rössle-Straße 10, 13125 Berlin, Germany

3Freie Universität Berlin, Institut für Mathematik, Arnimallee 6, 14195 Berlin, Germany

4Leibniz-Institut für Molekulare Pharmakologie, Robert-Rössle-Straße 10, 13125 Berlin, Germany

5Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Forschungseinrichtung Strukturanalyse, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany

6Freie Universität Berlin, Institut für Chemie und Biochemie, Takustraße 6, 14195 Berlin, Germany

* These authors contributed equally to this work.

A photo of Professor Oliver Daumke and Dr. Katja Fälber can be downloaded from the Internet

Contact:

Barbara Bachtler

Press Department

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) Berlin-Buch

in the Helmholtz Association

Robert-Rössle-Straße 10

13125 Berlin

Germany

Phone: +49 (0) 30 94 06 - 38 96

Fax: +49 (0) 30 94 06 - 38 33

e-mail: presse@mdc-berlin.de

http://www.mdc-berlin.de/de

Further information:

Professor Oliver Daumke, oliver.daumke@mdc-berlin.de, Phone: +49 (0)30 94 06 - 3425

Dr. Susanne Eschenburg, Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Phone: +49 (0)511 532 - 8655, eschenburg.susanne@mh-hannover.de

Products labeled with a Fair Trade logo cause prospective buyers to dig deeper into their pockets. In an experiment conducted at the University of Bonn, participants were willing to pay on average 30 percent more for ethically produced goods, compared to their conventionally produced counterparts. The neuroscientists analyzed the neural pathways involved in processing products with a Fair Trade emblem. They identified a potential mechanism that explains why Fair Trade products are evaluated more positively. For instance, activity in the brain's reward center increases and ...

This news release is available in German. The yields of many important crops in Europe have been stagnating since the 1990s. As a result, the input of organic matter into the soil - the crucial source for humus formation - is decreasing. Scientists from the Technical University Munich (TUM) suspect that the humus stocks of arable soils are declining due to the influence of climate change. Humus, however, is a key factor for soil functionality, which is why this development poses a threat to agricultural production - and, moreover, in a worldwide context.

In their ...

Young adults diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adolescence show differences in brain structure and perform poorly in memory tests compared to their peers, according to new research from the University of Cambridge, UK, and the University of Oulu, Finland.

The findings, published today in the journal European Child Adolescent Psychiatry, suggest that aspects of ADHD may persist into adulthood, even when current diagnostic criteria fail to identify the disorder.

ADHD is a disorder characterised by short attention span, restlessness and ...

This news release is available in French and Portuguese. Health providers trained to perform malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) are still prescribing valuable malaria medicines to patients who do not have malaria, according to new research published in PLOS ONE.

Almost 5,000 participants from 40 communities took part in the study, at a variety of public health facilities, pharmacies and drug stores in the Nigerian state of Enugu. Despite the three different training interventions that they received and their satisfaction with the courses and materials, rates of ...

A study conducted with experienced scholars of Zen-Meditation shows that mental focussing can induce learning mechanisms, similar to physical training. Researchers at the Ruhr-University Bochum and the Ludwig-Maximilians-University München discovered this phenomenon during a scientifically monitored meditation retreat. The journal Scientific Reports, from the makers of Nature, has now published their new findings on the plasticity of the brain.

Participants of the study use a special meditation technique

The participants were all Zen-scholars with many years of ...

Researchers led by the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health examined HIV testing trends among adults ages 50 through 64 both before and after 2006, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that most doctors automatically screen all patients for HIV regardless of whether they have symptoms.

The researchers found that gains in HIV testing were not sustained over time. Levels of engagement in HIV risk behaviors remained constant, yet testing decreased among this age group from 5.5 percent in 2003 to 3.6 percent in 2006. It increased immediately ...

It's bacteria against bacteria, and one of them is going down.

Two UC Santa Barbara graduate students have demonstrated how certain microbes exploit proteins in nearby bacteria to deliver toxins and kill them. The mechanisms behind this bacterial warfare, the researchers suggest, could be harnessed to target pathogenic bacteria. Their findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Lead authors Julia L.E. Willett and Grant C. Gucinski have detailed how gram-negative bacteria use contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) systems to infiltrate ...

Some children react more strongly to negative experiences than others. Researchers from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) have found a link between aggression and variants of a particular gene.

But children who react most aggressively also tend to respond more strongly to good experiences, the Norwegian researchers found. These children's mood swings have deeper valleys, but also greater peaks.

Aggression is common in young children. Aggressive behaviour increases until children are around 4 years old, and then gradually subsides.

Research ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- A study provides multiple lines of new evidence that pigments and the microbodies that produce them can remain evident in a dinosaur fossil. In the journal Scientific Reports, an international team of paleontologists correlates the distinct chemical signature of animal pigment with physical evidence of melanosome organelles in the fossilized feathers of Anchiornis huxleyi, a bird-like dinosaur that died about 150 million years ago in China.

The idea that melanosomes, which produce melanin pigment, are preserved in fossils has been ...

Physicists have found a radical new way confine electromagnetic energy without it leaking away, akin to throwing a pebble into a pond with no splash.

The theory could have broad ranging applications from explaining dark matter to combating energy losses in future technologies.

However, it appears to contradict a fundamental tenet of electrodynamics, that accelerated charges create electromagnetic radiation, said lead researcher Dr Andrey Miroshnichenko from The Australian National University (ANU).

"This problem has puzzled many people. It took us a year to get this ...