(Press-News.org) Young adults diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adolescence show differences in brain structure and perform poorly in memory tests compared to their peers, according to new research from the University of Cambridge, UK, and the University of Oulu, Finland.

The findings, published today in the journal European Child Adolescent Psychiatry, suggest that aspects of ADHD may persist into adulthood, even when current diagnostic criteria fail to identify the disorder.

ADHD is a disorder characterised by short attention span, restlessness and impulsivity, and is usually diagnosed in childhood or adolescence. Estimates suggest that more than three in every 100 boys and just under one in every 100 girls has ADHD. Less is known about the extent to which the disorder persists into adulthood, with estimates suggesting that between 10-50% of children still have ADHD in adulthood. Diagnosis in adulthood is currently reliant on meeting symptom checklists (such as the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual).

Some have speculated that as the brain develops in adulthood, children may grow out of ADHD, but until now there has been little rigorous evidence to support this. So far, most of the research that has followed up children and adolescents with ADHD into adulthood has focused on interview-based assessments, leaving questions of brain structure and function unanswered.

Now, researchers at Cambridge and Oulu have followed up 49 adolescents diagnosed with ADHD at age 16, to examine their brain structure and memory function in young adulthood, aged between 20-24 years old, compared to a control group of 34 young adults. The research was based within the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986, which has followed up thousands of children born in 1986 from gestation and birth into adulthood. The results showed that the group diagnosed in adolescence still had problems in terms of reduced brain volume and poorer memory function, irrespective of whether or not they still met diagnostic checklist criteria for ADHD.

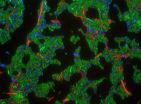

By analysing the structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans and comparing them to the controls, the researchers found that the adolescents with ADHD had reduced grey matter in a region deep within the brain known as the caudate nucleus, a key brain region that integrates information across different parts of the brain, and supports important cognitive functions, including memory.

To investigate whether or not these grey matter deficits were of any importance, the researchers conducted a functional MRI experiment (fMRI), which measured brain activity whilst 21 of the individuals previously diagnosed with ADHD and 23 of the controls undertook a test of working memory inside the scanner.

One third of the adolescents with ADHD failed the memory test compared to less than one in twenty of the control group (an accuracy of less than 75% was classed as a fail). Even amongst the adolescent ADHD sample who passed the memory test, the scores were on average 6 percentage points less than controls. The poor memory scores seemed to relate to a lack of responsiveness in the activity of the caudate nucleus: in the controls, when the memory questions became more difficult, the caudate nucleus became more active, and this appeared to help the control group perform well; in the adolescent ADHD group, the caudate nucleus kept the same level of activity throughout the test.

There were no differences in brain structure or memory test scores between those young adults previously diagnosed with ADHD who still met the diagnostic criteria and those who no longer met them.

Dr Graham Murray from the Department of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, who led the study, says: "In the controls, when the test got harder, the caudate nucleus went up a gear in its activity, and this is likely to have helped solve the memory problems. But in the group with adolescent ADHD, this region of the brain is smaller and doesn't seem to be able to respond to increasing memory demands, with the result that memory performance suffers.

"We know that good memory function supports a variety of other mental processes, and memory problems can certainly hold people back in terms of success in education and the workplace. The next step in our research will be to examine whether these differences in brain structure and memory function are linked to difficulties in everyday life, and, crucially, see if they respond to treatment."

The fact that the study was set in Finland, where medication is rarely used to treat ADHD, meant that only one of the 49 ADHD adolescents had been treated with medication. This meant the researchers could confidently rule out medication as a confounding factor.

To date, 'recovery' in ADHD has focused on whether people do or do not continue to meet symptom checklist criteria for diagnosis. However, this research indicates that objective measures of brain structure and function may continue to be abnormal even if diagnostic criteria are no longer met. The results therefore emphasize the importance of taking a wider perspective on ADHD outcomes than simply whether or not a particular patient meets diagnostic criteria at any given point in time.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported in part by the Medical Research Council, with additional support from the Wellcome Trust and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Reference

Roman-Urrestarazu, A et al. Brain structural deficits and working memory fMRI dysfunction in young adults who were diagnosed with ADHD in adolescence. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry; 27 Aug 2015

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00787-015-0755-8

This news release is available in French and Portuguese. Health providers trained to perform malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) are still prescribing valuable malaria medicines to patients who do not have malaria, according to new research published in PLOS ONE.

Almost 5,000 participants from 40 communities took part in the study, at a variety of public health facilities, pharmacies and drug stores in the Nigerian state of Enugu. Despite the three different training interventions that they received and their satisfaction with the courses and materials, rates of ...

A study conducted with experienced scholars of Zen-Meditation shows that mental focussing can induce learning mechanisms, similar to physical training. Researchers at the Ruhr-University Bochum and the Ludwig-Maximilians-University München discovered this phenomenon during a scientifically monitored meditation retreat. The journal Scientific Reports, from the makers of Nature, has now published their new findings on the plasticity of the brain.

Participants of the study use a special meditation technique

The participants were all Zen-scholars with many years of ...

Researchers led by the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health examined HIV testing trends among adults ages 50 through 64 both before and after 2006, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that most doctors automatically screen all patients for HIV regardless of whether they have symptoms.

The researchers found that gains in HIV testing were not sustained over time. Levels of engagement in HIV risk behaviors remained constant, yet testing decreased among this age group from 5.5 percent in 2003 to 3.6 percent in 2006. It increased immediately ...

It's bacteria against bacteria, and one of them is going down.

Two UC Santa Barbara graduate students have demonstrated how certain microbes exploit proteins in nearby bacteria to deliver toxins and kill them. The mechanisms behind this bacterial warfare, the researchers suggest, could be harnessed to target pathogenic bacteria. Their findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Lead authors Julia L.E. Willett and Grant C. Gucinski have detailed how gram-negative bacteria use contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) systems to infiltrate ...

Some children react more strongly to negative experiences than others. Researchers from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) have found a link between aggression and variants of a particular gene.

But children who react most aggressively also tend to respond more strongly to good experiences, the Norwegian researchers found. These children's mood swings have deeper valleys, but also greater peaks.

Aggression is common in young children. Aggressive behaviour increases until children are around 4 years old, and then gradually subsides.

Research ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- A study provides multiple lines of new evidence that pigments and the microbodies that produce them can remain evident in a dinosaur fossil. In the journal Scientific Reports, an international team of paleontologists correlates the distinct chemical signature of animal pigment with physical evidence of melanosome organelles in the fossilized feathers of Anchiornis huxleyi, a bird-like dinosaur that died about 150 million years ago in China.

The idea that melanosomes, which produce melanin pigment, are preserved in fossils has been ...

Physicists have found a radical new way confine electromagnetic energy without it leaking away, akin to throwing a pebble into a pond with no splash.

The theory could have broad ranging applications from explaining dark matter to combating energy losses in future technologies.

However, it appears to contradict a fundamental tenet of electrodynamics, that accelerated charges create electromagnetic radiation, said lead researcher Dr Andrey Miroshnichenko from The Australian National University (ANU).

"This problem has puzzled many people. It took us a year to get this ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Many clinical trials use genome sequencing to learn which gene mutations are present in a patient's tumor cells. The question is important because targeting the right mutations with the right drugs can stop cancer in its tracks. But it can be difficult to determine whether there is evidence in the medical literature that particular mutations might drive cancer growth and could be targeted by therapy, and which mutations are of no consequence.

To help molecular pathologists, laboratory directors, bioinformaticians and oncologists identify key mutations ...

A study by the University of Liverpool has found that the genetic diversity of wild plant species could be altered rapidly by anthropogenic climate change.

Scientists studied the genetic responses of different wild plant species, located in a natural grassland ecosystem near Buxton, to a variety of simulated climate change treatments--including drought, watering, and warming--over a 15-year period.

Analysis of DNA markers in the plants revealed that the climate change treatments had altered the genetic composition of the plant populations. The results also indicated a ...

Twitter offers a public platform for people to post and share all sorts of content, from the serious to the ridiculous. While people tend to share political information with those who have similar ideological preferences, new research from NYU's Social Media and Political Participation Lab demonstrates that Twitter is more than just an "echo chamber."

The research is published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Platforms like Twitter or Facebook are creating unprecedented opportunities for citizens to communicate with ...