Protein twist and squeeze confers cancer drug resistance

iCeMS scientists have revealed how a transporter protein twists and squeezes compounds out of cells, including chemotherapy drugs from some cancer cells

2021-01-02

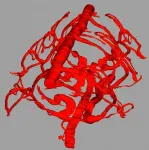

(Press-News.org) In 1986, cellular biochemist Kazumitsu Ueda, currently at Kyoto University's Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS), discovered that a protein called ABCB1 could transport multiple chemotherapeutics out of some cancer cells, making them resistant to treatment. How it did this has remained a mystery for the past 35 years. Now, his team has published a review in the journal FEBS Letters, summarizing what they have learned following years of research on this and other ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter proteins.

ABC transporter proteins are very similar across species and have various transportation roles: importing nutrients into cells, exporting toxic compounds outside them, and regulating lipid concentrations within cell membranes.

ABCB1 is one of these proteins, and is responsible for exporting toxic compounds out of the cell in vital organs such as the brain, testes, and placenta. Sometimes, though, it can also export chemotherapeutic drugs from cancer cells, making them resistant to treatment. The protein lies across the cell membrane, with one end reaching into the cell and the other poking out into the surrounding space. Even though scientists have known its roles and structure for years, exactly how it functions has been unclear.

Ueda and his team crystalized the ABCB1 protein before and after it exported a compound. They then conducted X-ray tests to determine the differences between the two structures. They also conducted analyses using ABCB1 fused with fluorescent proteins to monitor the conformational changes during transport.

They found that compounds destined for export access ABCB1's cavity through a gate in the part of the protein lying inside of the cell membrane. The compound rests at the top of the cavity, where it attaches to molecules, triggering a structural change in the protein. This change requires energy, which is derived from the energy-carrying molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP). When magnesium ions bind to ATP, the part of ABCB1 inside the cell packs tightly in on itself and tilts, causing its cavity to shrink and then close. This opens the protein's exit gate. ATP is also involved in making ABCB1 progressively rigid from its bottom to its top, leading to a twist and squeeze motion that expels the compound into the extracellular space.

"This mechanism is distinct from those of other transporter proteins," says Ueda. "We expect our work will facilitate the study of other ABC proteins, such as those involved in cholesterol homeostasis."

INFORMATION:

DOI: 10.1002/1873-3468.14018

About Kyoto University's Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS):

At iCeMS, our mission is to explore the secrets of life by creating compounds to control cells, and further down the road to create life-inspired materials.

https://www.icems.kyoto-u.ac.jp/

For more information, contact:

I. Mindy Takamiya/Mari Toyama

pe@mail2.adm.kyoto-u.ac.jp

YouTube video:

https://youtu.be/OpF6w7Rnom4

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-02

Scientists have suspected mutations in a cellular cholesterol transport protein are associated with psychiatric disorders, but have found it difficult to prove this and to pinpoint how it happens. Now, Kazumitsu Ueda of Kyoto University's Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS) and colleagues in Japan have provided evidence that mice with disrupted ABCA13 protein demonstrate a hallmark behaviour of schizophrenia. The team investigated ABCA13's functions and published their findings in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

ABCA13 belongs to a family of cellular transporter proteins called ATP-binding ...

2021-01-02

Philadelphia, December 29, 2020 - Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex psychiatric disorder brought on by physical and/or psychological trauma. How its symptoms, including anxiety, depression and cognitive disturbances arise remains incompletely understood and unpredictable. Treatments and outcomes could potentially be improved if doctors could better predict who would develop PTSD. Now, researchers using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have found potential brain biomarkers of PTSD in people with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

The study appears in ...

2021-01-02

What happens in the brain when our conscious awareness fades during general anesthesia and normal sleep? Finnish scientists studied this question with novel experimental designs and functional brain imaging. They succeeded in separating the specific changes related to consciousness from the more widespread overall effects, and discovered that the effects of anesthesia and sleep on brain activity were surprisingly similar. These novel findings point to a common central core brain network fundamental for human consciousness.

Explaining the biological basis of human ...

2021-01-02

A fascinating substance with unique properties, ice has intrigued humans since time immemorial. Unlike most other materials, ice at very low temperature is not as ordered as it could be. A collaboration between the Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati (SISSA), the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), the Institute of Physics Rosario (IFIR-UNR), with the support of the Istituto Officina dei Materiali of the Italian National Research Council (CNR-IOM), made new theoretical inroads on the reasons why this happens and on the way in which some of the missing order can be recovered. In that ordered state the team ...

2021-01-02

Small studies have suggested that a group of medications called RAS inhibitors may be harmful in persons with advanced chronic kidney disease, and physicians therefore often stop the treatment in such patients. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet now show that although stopping the treatment is linked to a lower risk of requiring dialysis, it is also linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular events and death. The results are published in The Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects approximately ten percent of the global population. Hypertension is ...

2021-01-02

Scientific articles in the field of physics are mostly very short and deal with a very restricted topic. A remarkable exception to this is an article published recently by physicists from the Universities of Münster and Düsseldorf. The article is 127 pages long, cites a total of 1075 sources and deals with a wide range of branches of physics - from biophysics to quantum mechanics.

The article is a so-called review article and was written by physicists Michael te Vrugt and Prof. Raphael Wittkowski from the Institute of Theoretical Physics and the Center for Soft Nanoscience at the University of Münster, together with ...

2021-01-02

Although plants are anchored to the ground, they spend most of their lifetime swinging in the wind. Like animals, plants have 'molecular switches' on the surface of their cells that transduce a mechanical signal into an electrical one in milliseconds. In animals, sound vibrations activate 'molecular switches' located in the ear. Scientists from the CNRS, INRAE, Ecole Polytechnique, Université Paris-Saclay and Université Clermont-Auvergne (1) have found that in plants, rapid oscillations of stems and leaves ...

2021-01-02

How can cells adhere to surfaces and move on them? This is a question which was investigated by an international team of researchers headed by Prof. Michael Hippler from the University of Münster and Prof. Kaiyao Huang from the Institute of Hydrobiology (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, China). The researchers used the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as their model organism. They manipulated the alga by altering the sugar modifications in proteins on the cell surface. As a result, they were able to alter the cellular surface adhesion, also known as adhesion force. The results have now been published in the ...

2021-01-02

Thanks to the marine worm Platynereis dumerilii, an animal whose genes have evolved very slowly, scientists from CNRS, Université de Paris and Sorbonne Université, in association with others at the University of Saint Petersburg and the University of Rio de Janeiro, have shown that while haemoglobin appeared independently in several species, it actually descends from a single gene transmitted to all by their last common ancestor. These findings were published on 29 December 2020 in BMC Evolutionary Biology.

Having red blood is not peculiar to humans or mammals. ...

2021-01-02

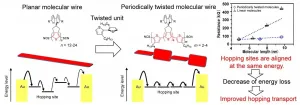

Osaka, Japan - Researchers at Osaka University synthesized twisted molecular wires just one molecule thick that can conduct electricity with less resistance compared with previous devices. This work may lead to carbon-based electronic devices that require fewer toxic materials or harsh processing methods.

Organic conductors, which are carbon-based materials that can conduct electricity, are an exciting new technology. Compared with conventional silicon electronics, organic conductors can be synthesized more easily, and can even be made into molecular wires. However, these structures suffer from reduced electrical conductivity, which prevents ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Protein twist and squeeze confers cancer drug resistance

iCeMS scientists have revealed how a transporter protein twists and squeezes compounds out of cells, including chemotherapy drugs from some cancer cells