(Press-News.org) To control mosquito populations and prevent them from transmitting diseases such as malaria, many researchers are pursuing strategies in mosquito genetic engineering. A new Texas A&M AgriLife Research project aims to enable temporary "test runs" of proposed genetic changes in mosquitoes, after which the changes remove themselves from the mosquitoes' genetic code.

The project's first results were published on Dec. 28 in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, titled "Making gene drive biodegradable."

Zach Adelman, Ph.D, and Kevin Myles, Ph.D., both professors in the Texas A&M College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Department of Entomology are the principal investigators. Over five years, the team will receive $3.9 million in funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to test and fine-tune the self-deleting gene technology.

"People are wary of transgenes spreading in the environment in an uncontrolled manner. We feel that ours is a strategy to potentially prevent that from happening," Adelman said. "The idea is, can we program a transgene to remove itself? Then, the gene won't persist in the environment.

"What it really comes down to is, how do you test a gene drive in a real-world scenario?" he added. "What if a problem emerges? We think ours is one possible way to be able to do risk assessment and field testing."

A crucial target for mosquito control

Many genetic engineering proposals revolve around inserting into mosquitoes a select set of new genes along with a "gene drive." A gene drive is a genetic component that forces the new genes to spread in the population.

"A number of high-profile publications have talked about using a gene drive to control mosquitoes, either to change them so they can't transmit malaria parasites anymore, or to kill off all the females so the population dies out," Adelman said.

An often-voiced worry is that such genetic changes could carry unintended or harmful consequences.

One plan makes the cut

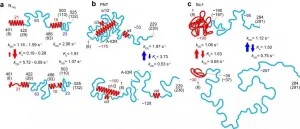

In the project's first publication, the colleagues describe three ways for an introduced genetic change to remove itself after a designated period of time. The time period could, for instance, be 20 generations of mosquitoes, or about a year. The team modeled how the genes would spread among mosquitoes based on generation times and parameters of an average mosquito's life. Of the three methods, the team has chosen one to pursue further.

This method takes advantage of a process all animals use to repair damaged DNA, Adelman said. Inside cell nuclei, repair enzymes search for repeated genetic sequences around broken DNA strands. The repair enzymes then delete what's between the repeats, he said.

So, Adelman and Myles' team plans to test in fruit flies and mosquitoes a gene drive, a DNA-cutting enzyme and a small repeat of the insect's own DNA.

Once the introduced enzyme cuts the DNA, the insect's own repair tools should jump into action. The repair tools will cut out the genes for the gene drive and the other added sequences. At least, that's what should happen in theory.

Failure is not just an option, it's part of the plan

The team has already started lab work to test different gene drives and determine how long they last in flies and mosquitoes. The goal is to see a gene drive spread rapidly through a lab insect population. After a few generations, the added genes should disappear and the population should again consist of wild-type individuals.

"We assigned various rates of failure for how often the mechanism does not work as expected," Adelman said. "The models predict that even with a very high rate of failure, if it succeeds just 5% of the time, that's still enough to get rid of the transgene."

INFORMATION:

What The Patient Page Says: We have all lived with COVID-19 for about a year now. Overall, we have learned that children get sick less often than adults, but a few children have gotten severely sick. This update summarizes the current understanding of how children are affected and gives ways to keep families safe as children continue to grow and thrive.

Authors: Lindsay A. Thompson, M.D., M.S., and Sonja A. Rasmussen, M.D., M.S., of the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville, are the authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5817)

Editor's ...

What The Study Did: Researchers looked at whether health outcomes of white citizens living in the richest U.S. counties were better than that of average individuals in other developed countries.

Authors: Ezekiel J. Emanuel, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7484)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

What The Study Did: This observational study examined whether lasting change in sweetened beverage prices or the volume sold was associated with the implementation and repeal of a sweetened beverage tax in Cook County, Illinois, where Chicago is.

Authors: Lisa M. Powell, Ph.D., of the University of Illinois Chicago, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31083)

Editor's Note: The article includes ...

Our understanding of biological proteins does not always correlate with how common or important they are. Half of all proteins, molecules that play an integral role in cell processes, are intrinsically disordered, which means many of the standard techniques for probing biomolecules don't work on them. Now researchers at Kanazawa University in Japan have shown that their home-grown high-speed atomic force microscopy technology can provide information not just on the structures of these proteins but also their dynamics.

Understanding how a protein is put together provides valuable clues to its functions. ...

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) is the basis of life on earth. The function of DNA is to store all the genetic information, which an organism needs to develop, function and reproduce. It is essentially a biological instruction manual found in every cell. Biochemists at the University of Münster have now developed a strategy for controlling the biological functions of DNA with the aid of light. This enables researchers to better understand and control the different processes which take place in the cell - for example epigenetics, the key chemical change and regulatory lever in DNA. The ...

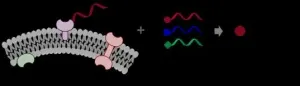

A research team led by Dr Xiaoyu LI from the Research Division for Chemistry, Faculty of Science, in collaboration with Professor Yizhou LI from School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chongqing University and Professor Yan CAO from School of Pharmacy, Second Military Medical University in Shanghai has developed a new drug discovery method targeting membrane proteins on live cells.

Membrane proteins play important roles in biology, and many of them are high-value targets that are being intensively pursued in the pharmaceutical ...

New research produced jointly by The Swire Institute of Marine Science (SWIMS), Faculty of Science, The University of Hong Kong (HKU), and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), published recently in the scientific journal Restoration Ecology, shows the enormous potential of restoring lost oyster reefs, bringing significant environmental benefits.

Benefits of oyster reefs

Hong Kong was once home to thriving shellfish reefs, but due to a combination of factors including over-exploitation, coastal reclamation and pollution, shellfish populations have declined drastically. Restoring oyster reefs along urbanized ...

Angiosarcomas are clinically aggressive tumours that are more prevalent in Asian populations

Study led by Singapore clinician-scientists has found a way to classify angiosarcomas into three subtypes, allowing for more targeted treatment, better outcomes for patients and the development of new therapies

Findings were published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation in October this year

Singapore, 29 December 2020 - A new study led by clinician-scientists from the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), with collaborators from research institutions worldwide, has found that angiosarcomas have unique genomic and immune profiles which allow them ...

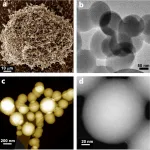

A fast, green and one-step method for producing porous carbon spheres, which are a vital component for carbon capture technology and for new ways of storing renewable energy, has been developed by Swansea University researchers.

The method produces spheres that have good capacity for carbon capture, and it works effectively at a large scale.

Carbon spheres range in size from nanometers to micrometers. Over the past decade they have begun to play an important role in areas such as energy storage and conversion, catalysis, gas adsorption and storage, drug and enzyme delivery, and water treatment.

They are also at the heart of carbon capture technology, ...

Researchers at the University of Turku have discovered what type of neural mechanisms are the basis for emotional responses to music. Altogether 102 research subjects listened to music that evokes emotions while their brain function was scanned with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The study was carried out in the national PET Centre.

The researchers used a machine learning algorithm to map which brain regions are activated when the different music-induced emotions are separated from each other.

- Based on the activation of the auditory and motor cortex, we were able to accurately predict whether the research subject was listening ...