An augmented immune response explains the adverse course of COVID-19 in patients with hypertension

- could ACE inhibitors offer protection?

2021-01-11

(Press-News.org) This most likely explains the augmented response of the immune system and the more severe disease progression. However, certain hypertension-reducing drugs known as ACE inhibitors can have a beneficial effect. They not only lower blood pressure, but also counteract immune hyperactivation. The scientists have now published their findings in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

More than one billion people worldwide suffer from high blood pressure, or hypertension. Of the more than 75 million people around the world who have become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus worldwide so far, more than 16 million also have hypertension. These patients are more likely to become severely ill, which in turn results in an increased risk of death. It was previously unclear to what extent treatment with antihypertensive drugs could be continued during a SARS-CoV-2 infection - and whether they were more likely to benefit or harm the patients. This is because antihypertensives interfere with the exact same regulatory mechanism that the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter the host cell and trigger COVID-19.

Professor Ulf Landmesser is Medical Director of the CharitéCenter 11 for Cardiovascular Diseases, Director of the Medical Department of Cardiology and BIH Professor of Cardiology on the Charité's Campus Benjamin Franklin in Berlin. He recognized early on that patients with hypertension or cardiovascular diseases often experienced a particularly critical disease progression with COVID-19. "The virus uses the receptor ACE2 as an entry portal into the cells, and the formation of this receptor is potentially influenced by the administration of antihypertensive drugs," explains Landmesser. "We had therefore initially feared that patients receiving ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers might have more ACE2 receptors on their cell surfaces and thus become more easily infected."

Certain drugs that lower blood pressure could also help with COVID-19

To clarify this suspicion, the scientists analyzed individual cells from the respiratory systems of COVID-19 patients who were also taking medication for high blood pressure. Dr. Sören Lukassen, a scientist in Professor Christian Conrad's group at the BIH Digital Health Center, explains that they were subsequently able to give the all-clear: "We found that the drugs do not seem to cause more receptors to form on the cells. As a result, we do not believe that they make it easier for the virus to enter the cells in this way and thus cause the more severe course of COVID-19." On the contrary, cardiovascular patients taking ACE inhibitors actually displayed a lower risk of becoming severely ill with COVID-19. In fact, they displayed almost the same level of risk as COVID-19 patients without cardiovascular problems.

Severe course of COVID-19 linked to pre-activation of the immune system

The blood of hypertensive patients usually shows elevated levels of inflammation, which can be fatal in the case of a SARS-CoV-2 infection. "Elevated inflammation levels are always a warning signal that COVID-19 will be more severe, regardless of any cardiovascular issues," explains Landmesser. The scientists therefore employed single-cell sequencing methods to investigate the immune response of hypertensive patients with COVID-19.

"We analyzed a total of 114,761 cells from the nasopharynx of 32 COVID-19 patients and 16 non-infected controls, with both groups including cardiovascular patients as well as people without cardiovascular problems," reports Dr. Saskia Trump, research group leader in the lab of Irina Lehmann, who is BIH Professor for Environmental Epigenetics and Lung Research. "We found that the immune cells of the cardiovascular patients displayed strong pre-activation even before infection with the novel coronavirus," explains Lehmann. "After contact with the virus, these patients were more likely to develop an augmented immune response, which was associated with the severe disease progression of COVID-19. However, our results also showed that treatment with ACE inhibitors, though not with angiotensin receptor blockers, could prevent this augmented immune response following infection by the coronavirus. ACE inhibitors could thus reduce the risk of patients with hypertension from experiencing severe disease progression."

Delayed reduction in viral load

Furthermore, the scientists found that the anti-hypertensive drugs can also impact how quickly the immune system is able to reduce the viral load, i.e., the concentration of the virus in the body. "Here, we observed a clear difference between the different forms of treatment for high blood pressure," notes Roland Eils, Director of the BIH Digital Health Center. "In the patients treated with angiotensin II receptor blockers, the reduction in viral load was significantly delayed, which could also contribute to a more severe course of COVID-19. We did not observe this delay in the patients who were receiving ACE inhibitors to treat their hypertension."

Interdisciplinary collaboration speeds up research

More than 40 scientists have been working at a breakneck pace on this extensive study. "The ability to quickly provide answers to urgent questions during the ongoing pandemic requires interdisciplinary collaboration among many committed individuals," explains Eils. "COVID-19 is such a complex disease that we brought together experts from cardiology, immunology, virology, pulmonary medicine, intensive care and computer science for this study. Our goal was to provide a scientifically sound answer as quickly as possible to the question of whether simultaneous treatment with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers could have beneficial or even adverse effects during the COVID-19 pandemic."

No evidence of increased risk of infection

Thanks to the study, the teams from the BIH, Charité and collaborating institutions in Leipzig and Heidelberg can now reassure both patients and the physicians treating them: "Our study provides no evidence that treatment with anti-hypertensive drugs increases the risk of infection by the novel coronavirus," says Ulf Landmesser, summarizing the results. "However, treating hypertension with ACE inhibitors could be more beneficial for patients suffering from COVID-19 than treatment with angiotensin II receptor blockers - a hypothesis that is currently being further investigated in randomized trials."

INFORMATION:

Original publication:

Saskia Trump#, Soeren Lukassen#, Markus S. Anker#, Robert Lorenz Chua#, Johannes Liebig#, Loreen Thürmann#, Victor Corman#, Marco Binder#, Jennifer Loske, Christina Klasa, Teresa Krieger, Bianca P. Hennig, Marey Messingschlager, Fabian Pott, Julia Kazmierski, Sven Twardziok, Jan Philipp Albrecht, Jürgen Eils, Sara Hadzibegovic, Alessia Lena, Bettina Heidecker, Christine Goffinet, Florian Kurth, Martin Witzenrath, Maria Theresa V.lker, Sarah Dorothea Müller, Uwe Gerd Liebert, Naveed Ishaque, Lars Kaderali, Leif- Erik Sander, Christian Drosten, Sven Laudi*, Roland Eils*, Christian Conrad*, Ulf Landmesser*, Irina Lehmann*, Hypertension delays viral clearance and exacerbates airway hyperinflammation in patients with COVID-19, Nat. Biotechnology DOI: 10.1038/s41587-020-00796-1

About the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH)

The mission of the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) is medical translation: transferring biomedical research findings into novel approaches to personalized prediction, prevention, diagnostics and therapy and, conversely, using clinical observations to develop new research ideas. The aim is to deliver relevant medical benefits to patients and the population at large. The BIH is also committed to establishing a comprehensive translational ecosystem as translational research area at the Charité - one that places emphasis on a system-wide understanding of health and disease and that promotes change in the biomedical research culture. The BIH is funded 90 percent by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and 10 percent by the State of Berlin. The two founding institutions, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC), were independent member entities within the BIH until 2020. As of 2021, the BIH has been integrated into the Charité as the so-called third pillar; the MDC is privileged partner of the BIH.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-11

NEW YORK, NY (Jan. 11, 2021)--Thousands of different genetic mutations have been implicated in cancer, but a new analysis of almost 10,000 patients found that regardless of the cancer's origin, tumors could be stratified in only 112 subtypes and that, within each subtype, the Master Regulator proteins that control the cancer's transcriptional state were virtually identical, independent of the specific genetic mutations of each patient.

The study, published Jan. 11 in Cell, confirms that Master Regulators provide the molecular logic that integrates the effect ...

2021-01-11

Philadelphia, January 11, 2021 - Children and adolescents with a family history of suicide attempts have lower executive functioning, shorter attention spans, and poorer language reasoning than those without a family history, according to a new study by researchers from the Lifespan Brain Institute (LiBI) of Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and the University of Pennsylvania. The study is the largest to date to examine the neurocognitive functioning of youth who have a biological relative who made a suicide attempt.

The findings, which were first published online last March, were published in the January 2021 edition of The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

Researchers looked at 3,507 youth aged 8 to 21. Of those, ...

2021-01-11

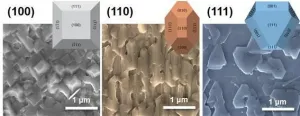

Russian researchers have proposed a new method for synthesizing high-quality graphene nanoribbons -- a material with potential for applications in flexible electronics, solar cells, LEDs, lasers, and more. Presented in The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, the original approach to chemical vapor deposition, offers a higher yield at a lower cost, compared with the currently used nanoribbon self-assembly on noble metal substrates.

Silicon-based electronics are steadily approaching their limits, and one wonders which material could give our devices the next big push. Graphene, the 2D sheet of carbon atoms, comes to mind but for all its celebrated electronic properties, it does not have what it takes: Unlike silicon, graphene does not have the ability to switch between ...

2021-01-11

CHICAGO (January 11, 2021): A new study of liver transplant centers confirms that non-Hispanic white patients get placed on liver transplant waitlists at disproportionately higher rates than non-Hispanic Black patients. However, researchers went a step further as they identified key reasons for that disparity: disproportionate access to private health insurance, travel distance to transplant centers, and a potential lack of knowledge among both practitioners and patients about available options. The study was selected for the 2020 Southern Surgical Association Program and published as an "article in press" on the website of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons in advance of print.

"We found that the Black population was underrepresented at the vast majority of centers, ...

2021-01-11

All-solid-state batteries are the next-generation batteries that can simultaneously improve the stability and capacity of existing lithium batteries. The use of non-flammable solid cathodes and electrolytes in such batteries considerably reduces the risk of exploding or catching fire under high temperatures or external impact and facilitates high energy density, which is twice that of lithium batteries. All-solid-state batteries are expected to become a game changer in the electric vehicle and energy storage device markets. Despite these advantages, the low ionic conductivity of solid electrolytes combined with their high interfacial resistance and rapid deterioration reduce battery performance and life, thus limiting their commercialization.

The ...

2021-01-11

Special Issue: Tumor Microenvironment and Drug Delivery

Guest Editors: Huile Gao, West China School of Pharmacy, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China; Zhiqing Pang, Fudan University, Shanghai, China and Wei He, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China

The Journal of the Institute of Materia Medica, the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and the Chinese Pharmaceutical Association, Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B (APSB) is a monthly journal, in English, which publishes significant original research articles, rapid communications and high quality reviews of recent advances in all areas of pharmaceutical sciences -- including pharmacology, pharmaceutics, medicinal chemistry, natural products, ...

2021-01-11

The Journal of the Institute of Materia Medica, the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and the Chinese Pharmaceutical Association, Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B (APSB) is a monthly journal, in English, which publishes significant original research articles, rapid communications and high quality reviews of recent advances in all areas of pharmaceutical sciences -- including pharmacology, pharmaceutics, medicinal chemistry, natural products, pharmacognosy, pharmaceutical analysis and pharmacokinetics.

Featured papers in this issue are:

Berberine diminishes cancer cell PD-L1 expression and facilitates antitumor immunity via inhibiting the deubiquitination activity of CSN5 by authors Yang Liu, Xiaojia Liu, Na Zhang, Mingxiao Yin, Jingwen Dong, Qingxuan ...

2021-01-11

"The findings provide an increased understanding of how the virus gets through the stomach and intestinal system. Continued research can provide answers to whether this property can also be used to create vaccines that ride 'free rides' and thus be given in edible form instead of as syringes," says Lars-Anders Carlson, researcher at Umeå University.

The virus that the researchers have studied is a so-called enteric adenovirus. It has recently been clarified that enteric adenoviruses are one of the most important factors behind diarrhea among infants, and they are estimated to kill more than 50,000 children under the age of five each year, ...

2021-01-11

Researchers from Trinity College Dublin have discovered a key mechanism underlying bacterial skin colonisation in atopic dermatitis, which affects millions around the globe.

Atopic dermatitis (AD, also called commonly eczema) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disorder in children, affecting 15-20% of people in childhood. During disease flares, patients experience painful inflamed skin lesions accompanied by intense itch and recurrent skin infection.

The bacterium Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) thrives on skin affected by AD, increasing inflammation and worsening AD symptoms. Although a small number of therapies are available at present for patients with moderate ...

2021-01-11

Leading research at Newcastle University has been used to shape how dentistry can be carried out safely during the Covid-19 pandemic by mitigating the risks of dental aerosols.

It is well known that coronavirus can spread in airborne particles, moving around rooms to infect people, and this has been a major consideration when looking into patient and clinician safety.

Research, published in the Journal of Dentistry, has led the way in helping shape national clinical guidance for the profession to work effectively under extremely challenging circumstances.

The findings have been used by the Dental Schools' Council, Association of Dental Hospitals and the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] An augmented immune response explains the adverse course of COVID-19 in patients with hypertension

- could ACE inhibitors offer protection?