(Press-News.org) Typically characterized as poisonous, corrosive and smelling of rotten eggs, hydrogen sulfide's reputation may soon get a face-lift thanks to Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers. In experiments in mice, researchers have shown the foul-smelling gas may help protect aging brain cells against Alzheimer's disease. The discovery of the biochemical reactions that make this possible opens doors to the development of new drugs to combat neurodegenerative disease.

The findings from the study are reported in the Jan. 11 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

"Our new data firmly link aging, neurodegeneration and cell signaling using hydrogen sulfide and other gaseous molecules within the cell," says Bindu Paul, M.Sc., Ph.D., faculty research instructor in neuroscience in the Solomon H. Snyder Department of Neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and lead corresponding author on the study.

The human body naturally creates small amounts of hydrogen sulfide to help regulate functions throughout the body, from cell metabolism to blood vessel dilation. The rapidly burgeoning field of gasotransmission shows that gases are major cellular messenger molecules, with particular importance in the brain. However, unlike conventional neurotransmitters, gases can't be stored in vesicles. Thus, gases act through very different mechanisms to rapidly facilitate cellular messaging. In the case of hydrogen sulfide, this entails the modification of target proteins by a process called chemical sulfhydration, which modulates their activity, says Solomon Snyder, D.Phil., D.Sc., M.D., professor of neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and co-corresponding author on the study.

Studies using a new method have shown that sulfhydration levels in the brain decrease with age, a trend that is amplified in patients with Alzheimer's disease. "Here, using the same method, we now confirm a decrease in sulfhydration in the AD brain," says collaborator Milos Filipovic, Ph.D., principal investigator, Leibniz-Institut für Analytische Wissenschaften - ISAS.

For the current research, the Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists studied mice genetically engineered to mimic human Alzheimer's disease. They injected the mice with a hydrogen sulfide-carrying compound called NaGYY, developed by their collaborators at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, which slowly releases the passenger hydrogen sulfide molecules while traveling throughout the body. The researchers then tested the mice for changes in memory and motor function over a 12-week period.

Behavioral tests on the mice showed that hydrogen sulfide improved cognitive and motor function by 50% compared with mice that did not receive the injections of NaGYY. Treated mice were able to better remember the locations of platform exits and appeared more physically active than their untreated counterparts with simulated Alzheimer's disease.

The results showed that the behavioral outcomes of Alzheimer's disease could be reversed by introducing hydrogen sulfide, but the researchers wanted to investigate how the brain chemically reacted to the gaseous molecule.

A series of biochemical experiments revealed a change to a common enzyme called glycogen synthase β (GSK3β). In the presence of healthy levels of hydrogen sulfide, GSK3β typically acts as a signaling molecule, adding chemical markers to other proteins and altering their function. However, the researchers observed that in the absence of hydrogen sulfide, GSK3β is overattracted to another protein in the brain called Tau.

When GSK3β interacts with Tau, Tau changes into a form that tangles and clumps inside nerve cells. As Tau clumps grow, the tangled proteins block communication between nerves, eventually causing them to die. This leads to the deterioration and eventual loss of cognition, memory and motor function that is characteristic of Alzheimer's disease.

"Understanding the cascade of events is important to designing therapies that can block this interaction like hydrogen sulfide is able to do," says Daniel Giovinazzo, M.D./Ph.D. student, the first author of the study.

Until recently, researchers lacked the pharmacological tools to mimic how the body slowly makes tiny quantities of hydrogen sulfide inside cells. "The compound used in this study does just that and shows by correcting brain levels of hydrogen sulfide, we could successfully reverse some aspects of Alzheimer's disease," says collaborator on the study Matt Whiteman, Ph.D., professor of experimental therapeutics at the University of Exeter Medical School.

The Johns Hopkins Medicine team and their international collaborators plan to continue studying how sulfur groups interact with GSK3β and other proteins involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease in other cell and organ systems. The team also plans to test novel hydrogen sulfide delivery molecules as part of their ongoing venture.

INFORMATION:

Other researchers involved in this study include Biljana Bursac, Thubaut Vignana and Milos Filipovic of the Leibniz-Institut für Analytische Wissenschaften - ISAS and Juan Sbodio, Sumedha Nalluru, Adele Snowman, Lauren Albacarys and Thomas Sedlak of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

This work was supported by the U.S. Public Health Service Grant (DA044123), the American Heart Association, the Allen Initiative in Brain Health and Cognitive Impairment, the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom (MR/S002626/1), the Brian Ridge Scholarship, and the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (864921).

The Johns Hopkins researchers declare no competing financial interests.

Climate changes prompt many important questions. Not least how it affects animals and plants: Do they adapts, gradually migrate to different areas or become extinct? And what is the role played by human activities? This applies not least to Greenland and the rest of the Artic, which are expected to see the greatest effects of climate changes.

'We know surprisingly little about marine species and ecosystems in the Arctic, as it is often costly and difficult to do fieldwork and monitor the biodiversity in this area', says Associate Professor of marine mammals and instigator of the study ...

Researchers from Skoltech and their colleagues have optimized data analysis for a common method of studying the 3D structure of DNA in single cells of a Drosophila fly. The new approach allows the scientists to peek with greater confidence into individual cells to study the unique ways DNA is packaged there and get closer to understanding this crucial process's underlying mechanisms. The paper was published in the journal Nature Communications.

The reason a roughly two-meter-long strand of DNA fits into the tiny nucleus of a human cell is that chromatin, a complex of DNA and proteins, packages it ...

A study of students at seven public universities across the United States has identified risk factors that may place students at higher risk for negative psychological impacts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Factors associated with greater risk of negative impacts include the amount of time students spend on screens each day, their gender, age and other characteristics.

Research has shown many college students faced significant mental health challenges going into the COVID-19 pandemic, and experts say the pandemic has added new stressors. The findings, published in the journal PLOS ONE, could help experts tailor services ...

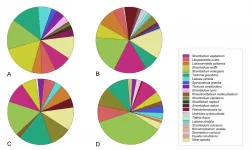

Announcing a new publication for Marine Life Science & Technology journal. In this research article the authors Hungchia Huang, Jinpeng Yang, Shixiang Huang, Bowei Gu, Ying Wang, Lei Wang and Nianzhi Jiao from Xiamen University, Xiamen, China and Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China consider the spatial distribution of planktonic ciliates in the western Pacific Ocea: along a transect from Shenzhen (China) to Pohnpei (Micronesia).

Planktonic ciliates have been recognized as major consumers of nano- and picoplankton in pelagic ecosystems, playing pivotal roles in the transfer ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. - As a former school nurse in the Columbia Public Schools, Gretchen Carlisle would often interact with students with disabilities who took various medications or had seizures throughout the day. At some schools, the special education teacher would bring in dogs, guinea pigs and fish as a reward for good behavior, and Carlisle noticed what a calming presence the pets seemed to be for the students with disabilities.

Now a research scientist at the MU Research Center for Human-Animal Interaction (ReCHAI) in the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, Carlisle studies the benefits that companion animals can have on families. While there is plenty of ...

New Orleans, LA - Catherine O'Neal, MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine at LSU Health New Orleans School of Medicine's branch campus in Baton Rouge, is a co-author of a paper reporting that shortening the length of quarantine due to COVID exposure when supported by mid-quarantine testing may increase compliance among college athletes without increasing risk. The findings are published in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's January 8, 2021 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), available here.

CDC partnered with representatives of the NCAA conferences to analyze retrospective data collected by participating colleges and universities. De-identified data from a total of 620 ...

Gut microbes passed from female mice to their offspring, or shared between mice that live together, may influence the animals' bone mass, says a new study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that treatments which alter the gut microbiome could help improve bone structure or treat conditions that weaken bones, such as osteoporosis.

"Genetics account for most of the variability in human bone density, but non-genetic factors such as gut microbes may also play a role," says lead author Abdul Malik Tyagi, Assistant Staff Scientist at the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Lipids at Emory Microbiome Research Center, Emory University, Georgia, US. "We wanted to investigate the influence of the microbiome on skeletal growth and bone mass development."

To ...

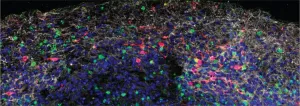

Using both mouse and human brain tissue, researchers at Yale School of Medicine have discovered that SARS-CoV-2 can directly infect the central nervous system and have begun to unravel some of the virus's effects on brain cells. The study, published today in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), may help researchers develop treatments for the various neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Though COVID-19 is considered to primarily be a respiratory disease, SARS-CoV-2 can affect many other organs in the body, including, in some patients, the central nervous system, where infection is associated with ...

The first step in treating cancer is understanding how it starts, grows and spreads throughout the body. A relatively new cancer research approach is the study of metabolites, the products of different steps in cancer cell metabolism, and how those substances interact.

To date, research like this has focused mostly on cancerous tissues; however, normal tissues that surround tumors, known as the extratumoral microenvironment (EM), may have conditions favorable for tumor formation and should also be studied.

In a new study published in the journal PLOS ONE, researchers investigated the metabolites involved in the growth and spread of melanoma, a rare but deadly ...

Almost 18,000 Americans experience traumatic spinal cord injuries every year. Many of these people are unable to use their hands and arms and can't do everyday tasks such as eating, grooming or drinking water without help.

Using physical therapy combined with a noninvasive method of stimulating nerve cells in the spinal cord, University of Washington researchers helped six Seattle area participants regain some hand and arm mobility. That increased mobility lasted at least three to six months after treatment had ended. The research team published these findings Jan. 5 in the journal ...