(Press-News.org) Decades after the industrialized world largely eliminated lead poisoning in children, the potent neurotoxin still lurks in one in three children globally. A new study in Bangladesh by researchers at Stanford University and other institutions finds that a relatively affordable remediation process can almost entirely remove lead left behind by unregulated battery recycling - an industry responsible for much of the lead soil contamination in poor and middle-income countries - and raises troubling questions about how to effectively eliminate the poison from children's bodies.

"Once the lead is in the environment, it stays there pretty much indefinitely without remediation," said study lead author Jenna Forsyth, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. "Ultimately, we want to work toward a world in which battery recycling is done safely, and lead never makes it into the soil or people's bodies in the first place."

Among toxins, lead is a supervillain. There is no safe level of exposure to lead, which damages nearly every system in the body. Early childhood exposure leads to irreversible brain damage and permanently lowered IQ, among other severe symptoms. Worldwide, one in three children suffers from lead poisoning, according to a recent report by Unicef and international NGO Pure Earth that describes the problem as "a much greater threat to the health of children than previously understood." The annual cost of resulting lost productivity is estimated to be nearly $1 trillion dollars globally and $16 billion in Bangladesh alone.

A dangerous industry's legacy

Lead acid batteries, such as those used in many cars and backup power storage systems, account for at least 80% of global lead use. In poor and middle-income countries, informal or "backyard" recycling of leaded batteries often uses highly polluting techniques, such as open-pit smelting, that put approximately 16 million people at risk of lead poisoning. An earlier assessment in Bangladesh found nearly 300 such recycling sites with elevated soil lead concentrations and estimated that nearly 700,000 people across the country are living within the contaminated sites.

To better understand informal battery recycling's impact on children, study partners from the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh, observed daily activities of people living adjacent to an abandoned battery recycling operation in rural Bangladesh and surveyed childcare givers. They noted, for instance, that women and children were regular visitors to the abandoned battery recycling site, spending hours a day there. The residents explored the area, scavenged battery scraps to use as household materials or toys, and even collected soil colored white by smelting ash to add visual appeal to their home exteriors, yards and earthen stoves. Children often played in the dirt, while women collected firewood and building materials or hung laundry out for drying in the area.

The researchers also tested children's blood before and after a multi-phased intervention that involved removing and burying contaminated soil, cleaning area households and educating residents about the dangers of soil lead exposure. Study partners from Dhaka University's Department of Geology and Pure Earth conducted the remediation work.

Challenges and solutions

Blood tests conducted prior to the remediation work showed many children had lead in their blood at levels up to 10 times higher than what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers elevated. And while the remediation effort led to a 96% reduction in lead soil concentrations over 14 months, the researchers were surprised to find child blood lead levels decreased only 35% on average during the same period.

The discrepancy may lie in the children's chronic soil lead exposure over a long enough time that lead stored in their bones continued to leach into their blood more than a year after the soil had been cleaned. A likely contributing reason, according to the researchers: other sources of lead exposure, such as turmeric adulterated with lead chromate and lead soldered cans used for food storage.

Additionally, the research team's housecleaning efforts were unable to remove and wash mattresses and upholstered furniture, which could have continued to harbor lead-contaminated dust. Other potential ongoing sources of contamination could have been home foundations or earthen stoves that local women amended with soil from the site.

"We are gratified that focused efforts to clean up the environment can help," said study co-author Stephen Luby, a professor of infectious diseases at Stanford's School of Medicine. "But with the huge burden of lead toxicity on children globally, more radical efforts to remove lead from the economy are needed."

Since 2014, Forsyth, Luby and other Stanford researchers have worked in rural Bangladesh to assess lead exposure. With funding from the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment's Environmental Venture Projects program, they first conducted a population assessment that found more than 30% of pregnant women had elevated blood lead levels.

Although the total cost of supplies and labor to implement the intervention - $40,300 - was relatively cheap by developed world standards, it's likely unfeasible in many regions of the developing world. The researchers suggest several ways to lower costs for such interventions, such as prioritizing house cleaning for children with the highest blood lead levels, but they emphasize the greater imperative to shift incentives away from informal battery recycling altogether.

Forsyth and Luby, together with researchers at Stanford's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, Graduate School of Business, d.school and International Policy Studies Program; are part of an initiative aimed at eliminating lead from the value chain or otherwise find ways to ensure it does not contaminate the environment. The effort, funded by the Stanford King Center on Global Development, focuses on reducing lead exposure from batteries and turmeric in Bangladesh.

INFORMATION:

Luby is also a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute and the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Stanford Maternal & Child Health Research Institute. Co-authors of the study also include a researcher from Virginia Commonwealth University.

The research was funded by the United States Agency for International Development, the European Commission and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

A new University of Saskatchewan (USask) study has found that stretching is superior to brisk walking for reducing blood pressure in people with high blood pressure or who are at risk of developing elevated blood pressure levels.

Walking has long been the prescription of choice for physicians trying to help their patients bring down their blood pressure. High blood pressure (hypertension) is a leading risk factor for cardiovascular disease and among the top preventable risk factors affecting overall mortality.

This new finding, published December 18, 2020 in the Journal of Physical Activity ...

On a beach on a remote island in eastern Papua New Guinea, a country located in the southwestern Pacific to the north of Australia, garnet sand reveals an important geologic discovery. Similar to messages in bottles that have traveled across the oceans, sediments derived from the erosion of rocks carry information from another time and place. In this case the grains of garnet sand reveal a story of traveling from the surface to deep into the Earth (~75 miles), and then returning to the surface before ending up on a beach as sand grains. Over the course of this geologic journey, the rock type changed as some minerals were changed, and other materials were included (trapped) within the newly formed garnets. The story is preserved ...

An antibacterial peptide that turns on and off

The researchers solved the 3D molecular structure of an antibacterial peptide named uperin 3.5, which is secreted on the skin of the Australian toadlet (Uperoleia mjobergii) as part of its immune system. They found that the peptide self-assembles into a unique fibrous structure, which via a sophisticated structural adaptation mechanism can change its form in the presence of bacteria to protect the toadlet from infections. This provides unique atomic-level evidence explaining a regulation mechanism of an antimicrobial ...

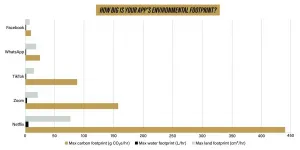

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. -- It's not just to hide clutter anymore - add "saving the planet" to the reasons you leave the camera off during your next virtual meeting.

A new study says that despite a record drop in global carbon emissions in 2020, a pandemic-driven shift to remote work and more at-home entertainment still presents significant environmental impact due to how internet data is stored and transferred around the world.

Just one hour of videoconferencing or streaming, for example, emits 150-1,000 grams of carbon dioxide (a gallon of gasoline burned from a car emits about 8,887 grams), requires 2-12 liters of water and demands a land area adding up to about the size of an iPad Mini.

But leaving your camera off during a web call can ...

January 14, 2021 - Orthopaedic surgeons have traditionally been taught that certain types of knee symptoms indicate damage to specialized structures called the menisci. But these "meniscal" and "mechanical" symptoms do not reflect what surgeons will find at knee arthroscopy, reports a study in The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio in partnership with Wolters Kluwer.

Both types of symptoms are strongly related to the overall amount of cartilage damage in the knee joint - but not to the presence of meniscal tears, according to the new research ...

In today's economy, American businesses often tap into professional management to grow, but most firms in India and other developing countries are family owned and often shun outside managers. A new study co-authored by Yale economist Michael Peters explores the effects that the absence of outside professional management has on India's businesses and the country's economy.

The study, published in the American Economic Review, uses a novel model to compare the relationship between the efficiency of outside managers and firm growth in the United States and India. It shows ...

Genome analysis can provide information on genes and their location on a strand of DNA, but such analysis reveals little about their spatial location in relation to one another within chromosomes -- the highly complex, three-dimensional structures that hold genetic information.

Chromosomes resemble a fuzzy "X" in microscopy images and can carry thousands of genes. They are formed when DNA winds around proteins -- called histones -- which are further folded into complexes called chromatin, which make up individual chromosomes.

Knowing which genes are located in spatial proximity within the chromatin is important because genes that are near each other generally work together.

Now, researchers at the END ...

Computational materials science experts at the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory enhanced an algorithm that borrows its approach from the nesting habits of cuckoo birds, reducing the search time for new high-tech alloys from weeks to mere seconds.

The scientists are investigating a type of alloys called high-entropy alloys, a novel class of materials that are highly sought after for a host of unusual and potentially beneficial properties. They are lightweight in relation to their strength, fracture-resistant, highly corrosion and oxidation resistant, and stand up well in high-temperature and high-pressure environments -- making them attractive materials for aerospace industry, space exploration, nuclear energy, and defense applications.

While the promise of these ...

Researchers from the PTSD Systems Biology Consortium, led by scientists from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, have identified distinct biotypes for post-traumatic stress disorder, the first of their kind for any psychological disorder. "These biotypes can refine the development of screening tools and may explain the varying efficacy of PTSD treatments", said Dr. Marti Jett, leader of the consortium and WRAIR chief scientist.

Publishing their work in Molecular Psychiatry in a manuscript first authored by WRAIR's Dr. Ruoting Yang, researchers used blood tests from male, combat-exposed veterans across a three year period to identify two PTSD biotypes, G1--characterized ...

TROY, N.Y. -- As cancer and tumor cells move inside the human body, they impart and are subject to mechanical forces. In order to understand how these actions affect cancer cell growth, spread, and invasion, a team of engineers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute is developing new models that mimic aspects of the mechanical environment within the body, providing new insight into how and why tumors develop in certain ways.

In research published today in Integrative Biology, a team of engineers from Rensselaer developed an in vitro -- in the lab -- lymphatic vessel model to study the growth of tumor emboli, collections of ...