(Press-News.org) Cell velocity, or how fast a cell moves, is known to depend on how sticky the surface is beneath it, but the precise mechanisms of this relationship have remained elusive for decades. Now, researchers from the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) and Ludwig Maximilians Universität München (LMU) have figured out the precise mechanics and developed a mathematical model capturing the forces involved in cell movement. The findings, reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), provide new insight for developmental biology and potential cancer treatment.

Cell movement is a fundamental process, especially critical during development when cells differentiate into their target cell type and then move to the correct tissue. Cells also move to repair wounds, while cancer cells crawl to the nearest blood vessel to spread to other parts of the body.

"The mathematical model we developed can now be used by researchers to predict how different cells will behave on various substrates," says Professor Martin Falcke, who heads MDC's Mathematical Cell Physiology Lab and co-led the research. "Understanding these basic movements in precise detail could provide new targets to interrupt tumor metastasis."

Teaming up to pin down

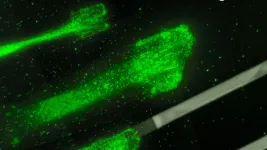

The finding comes thanks to experimental physicists at LMU teaming up with theoretical physicists at MDC. The experimentalists, led by Professor Joachim Rädler, tracked how quickly more than 15,000 cancer cells moved along narrow lanes on a sticky surface, where the stickiness alternated between low and high. This allowed them to observe what happens as the cell transitions between stickiness levels, which is more representative of the dynamic environment inside the body.

Then, Falcke and Behnam Amiri, co-first paper author and Ph.D. student in Falcke's lab, used the large dataset to develop a mathematical equation that captures the elements shaping cell motility.

"Previous mathematical models trying to explain cell migration and motility are very specific, they only work for one feature or cell type," Amiri says. "What we tried to do here is keep it as simple and general as possible."

The approach worked even better than expected: the model matched the data gathered at LMU and held true for measurements about several other cell types taken over the past 30 years. "This is exciting," Falcke says. "It's rare that you find a theory explaining such a large spectrum of experimental results."

Friction is key

When a cell moves, it pushes out its membrane in the direction of travel, expanding an internal network of actin filaments as it goes, and then peels off its back end. How fast this happens depends on adhesion bonds that form between the cell and the surface beneath it. When there are no bonds, the cell can hardly move because the actin network doesn't have anything to push off against. The reason is friction: "When you are on ice skates you cannot push a car, only when there is enough friction between your shoes and the ground can you push a car," Falcke says.

As the number of bonds increase, creating more friction, the cell can generate more force and move faster, until the point when it is so sticky, it becomes much harder to pull off the back end, slowing the cell down again.

Slow, but not stuck

The researchers investigated what happens when the front and rear ends of the cell experience different levels of stickiness. They were particularly curious to figure out what happens when it is stickier under the back end of the cell than the front, because that is when the cell could potentially get stuck, unable to generate enough force to pull off the back end.

This might have been the case if the adhesion bonds were more like screws, holding the cell to the substrate. At first, Falcke and Amiri included this type of "elastic" force in their model, but the equation only worked with friction forces.

"For me, the most challenging part was to wrap my mind around this mechanism working only with friction forces," Falcke says, because there is nothing for the cell to firmly latch onto. But it is the friction-like forces that allow the cell to keep moving, even when bonds are stronger in the back than the front, slowly peeling itself off like scotch tape. "Even if you pull just a little with a weak force, you are still able to peel the tape off - very slowly, but it comes off," Falcke says. "This is how the cell keeps itself from getting stuck."

The team is now investigating how cells move in two dimensions, including how they make hard right and left turns, and U-turns.

INFORMATION:

Imagine going to a surgeon to have a diseased or injured organ switched out for a fully functional, laboratory-grown replacement. This remains science fiction and not reality because researchers today struggle to organize cells into the complex 3D arrangements that our bodies can master on their own.

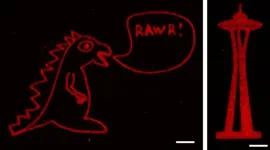

There are two major hurdles to overcome on the road to laboratory-grown organs and tissues. The first is to use a biologically compatible 3D scaffold in which cells can grow. The second is to decorate that scaffold with biochemical messages in the correct configuration to trigger the formation of the desired organ or tissue.

In a major step toward transforming this hope into reality, researchers at the University of Washington have developed a technique to ...

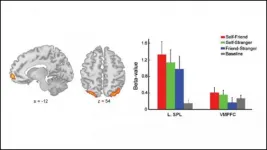

A brain region involved in processing information about ourselves biases our ability to remember, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

People are good at noticing information about themselves, like when your eye jumps to your name in a long list or you manage to hear someone address you in a noisy crowd. This self-bias extends to working memory, the ability to actively think about and manipulate bits of information: people are also better at remembering things about themselves.

To pinpoint the source of this bias, Yin et al. measured participants' brain activity in an fMRI scanner while they tried to remember the location of different colored dots representing themselves, a friend, or a stranger. The participants' fastest response ...

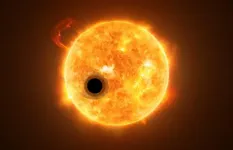

The core mass of the giant exoplanet WASP-107b is much lower than what was thought necessary to build up the immense gas envelope surrounding giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn, astronomers at Université de Montréal have found.

This intriguing discovery by Ph.D. student Caroline Piaulet of UdeM's Institute for Research on Exoplanets (iREx) suggests that gas-giant planets form a lot more easily than previously believed.

Piaulet is part of the groundbreaking research team of UdeM astrophysics professor Björn Benneke that in 2019 announced the first detection of water on an exoplanet located in its star's habitable zone.

Published today in the Astronomical Journal with colleagues ...

Indiana Jones and Lara Croft have a lot to answer for. Public perceptions of archaeology are often thoroughly outdated, and these characterisations do little to help.

Yet archaeology as practiced today bears virtually no resemblance to the tomb raiding portrayed in movies and video games. Indeed, it bears little resemblance to even more scholarly depictions of the discipline in the entertainment sphere.

A paper published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution aims to give pause to an audience that has been largely prepared to take such out-of-touch depictions at face value. It reveals an archaeology practiced by scientists in white lab coats, using multi-million-euro instrumentation and state of the art computers.

It also reveals an archaeology poised to ...

Irvine, Calif. -- Future climate change will cause a regionally uneven shifting of the tropical rain belt - a narrow band of heavy precipitation near the equator - according to researchers at the University of California, Irvine and other institutions. This development may threaten food security for billions of people.

In a study published today in Nature Climate Change, the interdisciplinary team of environmental engineers, Earth system scientists and data science experts stressed that not all parts of the tropics will be affected equally. For instance, the rain belt ...

Range anxiety, the fear of running out of power before being able to recharge an electric vehicle, may be a thing of the past, according to a team of Penn State engineers who are looking at lithium iron phosphate batteries that have a range of 250 miles with the ability to charge in 10 minutes.

"We developed a pretty clever battery for mass-market electric vehicles with cost parity with combustion engine vehicles," said Chao-Yang Wang, William E. Diefenderfer Chair of mechanical engineering, professor of chemical engineering and professor of materials science and engineering, and director of the Electrochemical Engine Center at Penn State. "There ...

Targeted neuromodulation tailored to individual patients' distinctive symptoms is an increasingly common way of correcting misfiring brain circuits in people with epilepsy or Parkinson's disease. Now, scientists at UC San Francisco's Dolby Family Center for Mood Disorders have demonstrated a novel personalized neuromodulation approach that -- at least in one patient -- was able to provide relief from symptoms of severe treatment-resistant depression within minutes.

The approach is being developed specifically as a potential treatment for the significant fraction of people with debilitating depression ...

More than 3,000 animal species in the world today are considered endangered, with hundreds more categorized as vulnerable. Currently, ecologists don't have reliable tools to predict when a species may become at risk.

A new paper published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, "Management implications of long transients in ecological systems," focuses on the transient nature of species' and ecosystem stability and illustrates how management practices can be adjusted to better prepare for possible system flips. Some helpful modeling approaches are also offered, including one tool that may help identify potentially ...

Researchers at the University of Adelaide have found new evidence about the positive role of androgens in breast cancer treatment with immediate implications for women with estrogen receptor-driven metastatic disease.

Published today in Nature Medicine, the international study conducted in collaboration with the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, looked at the role of androgens - commonly thought of as male sex hormones but also found at lower levels in women - as a potential treatment for estrogen receptor positive breast cancer.

Watch a video explainer about the new ...

Some of the low-carbon policy options currently used by governments may be detrimental to the households and small businesses less able to manage added short-term costs from energy price hikes, according to a new study.

However, it also suggests that this menu of decarbonising policies, from quotas to feed-in tariffs, can be designed and balanced to benefit local firms and lower-income families - vital for achieving 'Net Zero' carbon and a green recovery.

University of Cambridge researchers combed through thousands of studies to create the most comprehensive analysis to date of widely used types of low-carbon policy, and compared how they perform in areas such as cost and competitiveness. ...