(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Click beetles can propel themselves more than 20 body lengths into the air, and they do so without using their legs. While the jump's motion has been studied in depth, the physical mechanisms that enable the beetles' signature clicking maneuver have not. A new study examines the forces behind this super-fast energy release and provides guidelines for studying extreme motion, energy storage and energy release in other small animals like trap-jaw ants and mantis shrimps.

The multidisciplinary study, led by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign mechanical science and engineering professors Aimy Wissa and Alison Dunn, entomology professor Marianne Alleyne and mechanical science and engineering graduate student and lead author Ophelia Bolmin, is published in the Proceedings of that National Academy of Science.

Many insects use various mechanisms to overcome the limitations of their muscles. However, unlike other insects, click beetles use a unique hingelike tool in their thorax, just behind the head, to jump.

See a video describing this research [LINK: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lmsWcvW7fM&feature=youtu.be]

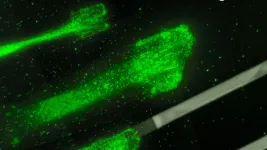

To determine how the hinge works, the team used high-speed X-rays to observe and quantify how a click beetle's body parts move before, during and after the ultrafast energy release.

"The hinge mechanism has a peg on one side that stays latched onto a lip on the other side of the hinge," Alleyne said. "When the latch is released, there is an audible clicking sound and a quick unbending motion that causes the beetle's jump."

Seeing this ultrafast motion using a visible-light camera helps the researchers understand what occurs outside the beetle. Still, it doesn't reveal how internal anatomy controls the flow of energy between the muscle, other soft structures and the rigid exoskeleton.

Using the X-ray video recordings and an analytical tool called system identification, the team identified and modeled the clicking motion forces and phases.

The researchers observed large, yet relatively slow deformations in the soft tissue part of the beetles' hinge in the lead-up to the fast unbending movement.

"When the peg in the hinge slips over the lip, the deformation in the soft tissue is released extremely quickly, and the peg oscillates back and forth in the cavity below the lip before coming to a stop," Wissa said. "The fast deformation release and repeated, yet decreasing, oscillations showcase two basic engineering principles called elastic recoil and damping."

The acceleration of this motion is more the 300 times that of the Earth's gravitational acceleration. That is a lot of energy coming from such a small organism, the researchers said.

"Surprisingly, the beetle can repeat this clicking maneuver without sustaining any significant physical damage," Dunn said. "That pushed us to focus on figuring out what the beetles use for energy storage, release and dissipation."

"We discovered that the insect uses a phenomenon called snap-buckling - a basic principle of mechanical engineering - to release elastic energy extremely quickly," Bolmin said. "It is the same principle that you find in jumping popper toys."

"We were surprised to find that the beetles use these basic engineering principles. If an engineer wanted to build a device that jumps like a click beetle, they would likely design it the same way nature did," Wissa said. "This work turned out to be a great example of how engineering can learn from nature and how nature demonstrates physics and engineering principles."

"These results are fascinating from an engineering perspective, and for biologists, this work gives us a new perspective on how and why click beetles evolved this way," Alleyne said. "This kind of insight may have never come to light, if not for this interdisciplinary collaboration between engineering and biology. It opens a new door for both fields."

INFORMATION:

John Socha of Virginia Tech and Kamel Fezzaa of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory helped collect the high-speed X-ray videos that enabled the discoveries in this paper.

The U.S. Department of Energy supported the study.

Wissa also is affiliated with aerospace engineering and the Carle Illinois College of Medicine. Dunn also is affiliated with the Carle Illinois College of Medicine and RAILtec. Alleyne also is affiliated with mechanical science and engineering and the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at Illinois.

Editor's notes:

To reach Aimy Wissa, call 217-244-4193; email awissa@illinois.edu.

The paper "Nonlinear elasticity and damping govern ultrafast dynamics in click beetles" is available online. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2014569118.

Scientists in Australia have developed a method for the rapid synthesis of safe vaccines, an approach that can be used to test vaccine strategies against novel pandemic pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Led by Professor Richard Payne at the University of Sydney and Professor Warwick Britton at the Centenary Institute, the team has demonstrated application of the method with a new vaccine for use against tuberculosis (TB), which has generated a powerful protective immune response in mice.

Researchers are keen to develop the vaccine strategy further to assist in the rapid pre-clinical testing of new vaccines, particularly for respiratory illnesses.

"Tuberculosis infects 10 million and kills more than 1.4 million people every year," ...

Cell velocity, or how fast a cell moves, is known to depend on how sticky the surface is beneath it, but the precise mechanisms of this relationship have remained elusive for decades. Now, researchers from the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) and Ludwig Maximilians Universität München (LMU) have figured out the precise mechanics and developed a mathematical model capturing the forces involved in cell movement. The findings, reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), provide new insight for developmental biology and potential cancer treatment.

Cell ...

Imagine going to a surgeon to have a diseased or injured organ switched out for a fully functional, laboratory-grown replacement. This remains science fiction and not reality because researchers today struggle to organize cells into the complex 3D arrangements that our bodies can master on their own.

There are two major hurdles to overcome on the road to laboratory-grown organs and tissues. The first is to use a biologically compatible 3D scaffold in which cells can grow. The second is to decorate that scaffold with biochemical messages in the correct configuration to trigger the formation of the desired organ or tissue.

In a major step toward transforming this hope into reality, researchers at the University of Washington have developed a technique to ...

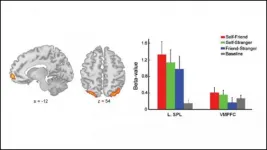

A brain region involved in processing information about ourselves biases our ability to remember, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

People are good at noticing information about themselves, like when your eye jumps to your name in a long list or you manage to hear someone address you in a noisy crowd. This self-bias extends to working memory, the ability to actively think about and manipulate bits of information: people are also better at remembering things about themselves.

To pinpoint the source of this bias, Yin et al. measured participants' brain activity in an fMRI scanner while they tried to remember the location of different colored dots representing themselves, a friend, or a stranger. The participants' fastest response ...

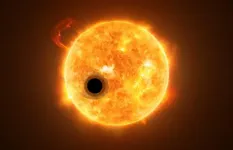

The core mass of the giant exoplanet WASP-107b is much lower than what was thought necessary to build up the immense gas envelope surrounding giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn, astronomers at Université de Montréal have found.

This intriguing discovery by Ph.D. student Caroline Piaulet of UdeM's Institute for Research on Exoplanets (iREx) suggests that gas-giant planets form a lot more easily than previously believed.

Piaulet is part of the groundbreaking research team of UdeM astrophysics professor Björn Benneke that in 2019 announced the first detection of water on an exoplanet located in its star's habitable zone.

Published today in the Astronomical Journal with colleagues ...

Indiana Jones and Lara Croft have a lot to answer for. Public perceptions of archaeology are often thoroughly outdated, and these characterisations do little to help.

Yet archaeology as practiced today bears virtually no resemblance to the tomb raiding portrayed in movies and video games. Indeed, it bears little resemblance to even more scholarly depictions of the discipline in the entertainment sphere.

A paper published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution aims to give pause to an audience that has been largely prepared to take such out-of-touch depictions at face value. It reveals an archaeology practiced by scientists in white lab coats, using multi-million-euro instrumentation and state of the art computers.

It also reveals an archaeology poised to ...

Irvine, Calif. -- Future climate change will cause a regionally uneven shifting of the tropical rain belt - a narrow band of heavy precipitation near the equator - according to researchers at the University of California, Irvine and other institutions. This development may threaten food security for billions of people.

In a study published today in Nature Climate Change, the interdisciplinary team of environmental engineers, Earth system scientists and data science experts stressed that not all parts of the tropics will be affected equally. For instance, the rain belt ...

Range anxiety, the fear of running out of power before being able to recharge an electric vehicle, may be a thing of the past, according to a team of Penn State engineers who are looking at lithium iron phosphate batteries that have a range of 250 miles with the ability to charge in 10 minutes.

"We developed a pretty clever battery for mass-market electric vehicles with cost parity with combustion engine vehicles," said Chao-Yang Wang, William E. Diefenderfer Chair of mechanical engineering, professor of chemical engineering and professor of materials science and engineering, and director of the Electrochemical Engine Center at Penn State. "There ...

Targeted neuromodulation tailored to individual patients' distinctive symptoms is an increasingly common way of correcting misfiring brain circuits in people with epilepsy or Parkinson's disease. Now, scientists at UC San Francisco's Dolby Family Center for Mood Disorders have demonstrated a novel personalized neuromodulation approach that -- at least in one patient -- was able to provide relief from symptoms of severe treatment-resistant depression within minutes.

The approach is being developed specifically as a potential treatment for the significant fraction of people with debilitating depression ...

More than 3,000 animal species in the world today are considered endangered, with hundreds more categorized as vulnerable. Currently, ecologists don't have reliable tools to predict when a species may become at risk.

A new paper published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, "Management implications of long transients in ecological systems," focuses on the transient nature of species' and ecosystem stability and illustrates how management practices can be adjusted to better prepare for possible system flips. Some helpful modeling approaches are also offered, including one tool that may help identify potentially ...