(Press-News.org) Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

1. Primary care physicians account for a minority of spending on low-value care

Abstract: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-6257

URL goes live when the embargo lifts

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are seen as gatekeepers to reduce spending on low-value health care services, which have been estimated to cost the health care system up to $100 billion annually. A brief research report published in Annals of Internal Medicine analyzed how much low-value spending is directly related to PCPs' services and referral decisions.

Researchers from the American Board of Family Medicine, Harvard, Mount Sinai, and Stanford analyzed Medicare Part B claims between 2007 and 2014 to estimate the share of Medicare beneficiaries' low-value spending that was directly related to their PCP's services or referrals. Low-value services were identified using a consensus set of 31 services previously judged to be low-value by national physician societies, Medicare criteria, and clinical guidelines. Such services include imaging for non-specific back pain, PSA screening for men over the age of 75, and arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis.

The data showed that PCP services and referrals account for a small minority of spending on low-value care. For the majority of PCPs, services they performed or ordered accounted for less than 9% of their patients' low-value spending, which amounted to less than 0.3% of their total Medicare Part B spending. Similarly, for most PCPs, their referrals accounted for less than 16% of their patients' low-value spending, which amounted to less than 0.5% of their total Medicare Part B spending.

Media contacts: For an embargoed PDF, please contact Lauren Evans at laevans@acponline.org. The corresponding author, Aaron Baum, PhD, can be reached through Jane Ireland at jireland@theabfm.org.

2. Hypothetical case suggests genetic testing has significant limitations for predicting disease in a healthy patient

Abstract: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-5713

URL goes live when the embargo lifts

Despite its utility as a diagnostic tool in patients with specific risk factors for genetic disease, genetic testing still has significant limitations for predicting disease in a healthy patient. Authors from Colombia University used a hypothetical case to illustrate differences between diagnostic testing and predictive genetic screening for prevention purposes, focusing on available clinical tests. Their case report is published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Healthy patients increasingly inquire about genetic testing as a tool for predicting diseases, such as cancer, heart disease, or dementia. In practice, most genetic testing is done in affected persons as a diagnostic tool or in healthy persons at high risk for genetic disease based on family history. Much less is known about the predictive value of genetic tests to screen healthy persons with no clear risk for genetic disease.

The researchers summarized current knowledge using on the hypothetical case of a healthy 35-year-old woman requesting genetic testing to predict her future risk for disease. Her maternal aunt and a male cousin had coronary heart disease by age 50 and a paternal aunt died of breast cancer at age 56. The scope of the genetic test can be determined on the basis of the risk profile and family history as well as the patient's concerns about specific diseases. For this patient, several genetic tests would be available, yet their value for predicting future disease could be very limited.

According to the researchers, in the diagnostic framework, detection of a pathogenic variant consistent with a person's clinical condition can establish a diagnosis of genetic disease. In the predictive framework, interpretation of genetic results is more complicated given the large number of putative pathogenic variants and the paucity of information about their clinical consequences. Even if the patient's genetic test revealed a genetic risk to a specific illness or illnesses, in most cases, the likelihood that she would develop the disease is not known Based on what is currently known about genetic testing as a predictive tool, the researchers conclude that a Bayesian framework is useful for assessing future risk of disease and predictive testing in clinical practice should be limited to genes where there is strong evidence linking mutations to high risk of disease.

Media contacts: For an embargoed PDF, please contact Lauren Evans at laevans@acponline.org. The corresponding author, Ali G. Gharavi, MD, can be contacted directly at ag2239@columbia.edu.

Also in this issue:

Corticosteroids and COVID-19: Calming the Storm?

Pearson

Hospitalist Commentary

https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-7671

Cancer and Deep Venous Thrombosis: A Serious Combination

Geno J. Merli, MD, Howard H. Weitz, MD

Consult Guys

https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/W20-0017

Low Dose Steroids and Risk of Infection

Robert M. Centor, MD

Annals On Call Podcast

https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/A20-0005

INFORMATION:

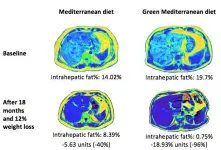

BEER-SHEVA, Israel...January 18, 2021 - A green Mediterranean (MED) diet reduces intrahepatic fat more than other healthy diets and cuts non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in half, according to a long-term clinical intervention trial led by Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers and a team of international colleagues.

The findings were published in Gut, a leading international journal focused on gastroenterology and hepatology.

"Our research team and other groups over the past 20 years have proven through rigorous randomized long-term trials that the Mediterranean diet is the healthiest," says lead researcher Prof. Iris Shai, an epidemiologist in the BGU ...

More people could be protected from life-threatening rabies thanks to an agile approach to dog vaccination using smart phone technology to spot areas of low vaccination coverage in real time.

Vets used a smart phone app to help them halve the time it takes to complete dog vaccination programmes in the Malawian city of Blantyre.

The custom-made app lets them quickly spot areas with low inoculation rates in real time, allowing them to jab more dogs more quickly, and with fewer staff.

Rabies is a potentially fatal disease passed on to humans primarily through dog bites. It is responsible for some 60,000 deaths worldwide each year, 40 per cent of which are children. It places a huge financial burden on some of the world's poorest countries.

Researchers predict that more than one million ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Click beetles can propel themselves more than 20 body lengths into the air, and they do so without using their legs. While the jump's motion has been studied in depth, the physical mechanisms that enable the beetles' signature clicking maneuver have not. A new study examines the forces behind this super-fast energy release and provides guidelines for studying extreme motion, energy storage and energy release in other small animals like trap-jaw ants and mantis shrimps.

The multidisciplinary study, led by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign mechanical science and ...

Scientists in Australia have developed a method for the rapid synthesis of safe vaccines, an approach that can be used to test vaccine strategies against novel pandemic pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Led by Professor Richard Payne at the University of Sydney and Professor Warwick Britton at the Centenary Institute, the team has demonstrated application of the method with a new vaccine for use against tuberculosis (TB), which has generated a powerful protective immune response in mice.

Researchers are keen to develop the vaccine strategy further to assist in the rapid pre-clinical testing of new vaccines, particularly for respiratory illnesses.

"Tuberculosis infects 10 million and kills more than 1.4 million people every year," ...

Cell velocity, or how fast a cell moves, is known to depend on how sticky the surface is beneath it, but the precise mechanisms of this relationship have remained elusive for decades. Now, researchers from the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) and Ludwig Maximilians Universität München (LMU) have figured out the precise mechanics and developed a mathematical model capturing the forces involved in cell movement. The findings, reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), provide new insight for developmental biology and potential cancer treatment.

Cell ...

Imagine going to a surgeon to have a diseased or injured organ switched out for a fully functional, laboratory-grown replacement. This remains science fiction and not reality because researchers today struggle to organize cells into the complex 3D arrangements that our bodies can master on their own.

There are two major hurdles to overcome on the road to laboratory-grown organs and tissues. The first is to use a biologically compatible 3D scaffold in which cells can grow. The second is to decorate that scaffold with biochemical messages in the correct configuration to trigger the formation of the desired organ or tissue.

In a major step toward transforming this hope into reality, researchers at the University of Washington have developed a technique to ...

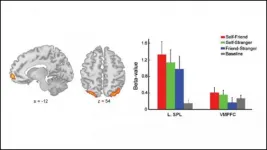

A brain region involved in processing information about ourselves biases our ability to remember, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

People are good at noticing information about themselves, like when your eye jumps to your name in a long list or you manage to hear someone address you in a noisy crowd. This self-bias extends to working memory, the ability to actively think about and manipulate bits of information: people are also better at remembering things about themselves.

To pinpoint the source of this bias, Yin et al. measured participants' brain activity in an fMRI scanner while they tried to remember the location of different colored dots representing themselves, a friend, or a stranger. The participants' fastest response ...

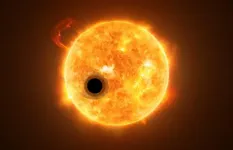

The core mass of the giant exoplanet WASP-107b is much lower than what was thought necessary to build up the immense gas envelope surrounding giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn, astronomers at Université de Montréal have found.

This intriguing discovery by Ph.D. student Caroline Piaulet of UdeM's Institute for Research on Exoplanets (iREx) suggests that gas-giant planets form a lot more easily than previously believed.

Piaulet is part of the groundbreaking research team of UdeM astrophysics professor Björn Benneke that in 2019 announced the first detection of water on an exoplanet located in its star's habitable zone.

Published today in the Astronomical Journal with colleagues ...

Indiana Jones and Lara Croft have a lot to answer for. Public perceptions of archaeology are often thoroughly outdated, and these characterisations do little to help.

Yet archaeology as practiced today bears virtually no resemblance to the tomb raiding portrayed in movies and video games. Indeed, it bears little resemblance to even more scholarly depictions of the discipline in the entertainment sphere.

A paper published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution aims to give pause to an audience that has been largely prepared to take such out-of-touch depictions at face value. It reveals an archaeology practiced by scientists in white lab coats, using multi-million-euro instrumentation and state of the art computers.

It also reveals an archaeology poised to ...

Irvine, Calif. -- Future climate change will cause a regionally uneven shifting of the tropical rain belt - a narrow band of heavy precipitation near the equator - according to researchers at the University of California, Irvine and other institutions. This development may threaten food security for billions of people.

In a study published today in Nature Climate Change, the interdisciplinary team of environmental engineers, Earth system scientists and data science experts stressed that not all parts of the tropics will be affected equally. For instance, the rain belt ...