Study finds COVID-19 attack on brain, not lungs, triggers severe disease in mice

The findings have implications for understanding the wide range in symptoms and severity of illness among humans who are infected by SARS-CoV-2

2021-01-19

(Press-News.org) ATLANTA--Georgia State University biology researchers have found that infecting the nasal passages of mice with the virus that causes COVID-19 led to a rapid, escalating attack on the brain that triggered severe illness, even after the lungs were successfully clearing themselves of the virus.

Assistant professor Mukesh Kumar, the study's lead researcher, said the findings have implications for understanding the wide range in symptoms and severity of illness among humans who are infected by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

"Our thinking that it's more of a respiratory disease is not necessarily true," Kumar said. "Once it infects the brain it can affect anything because the brain is controlling your lungs, the heart, everything. The brain is a very sensitive organ. It's the central processor for everything."

The study, published by the journal "Viruses," assessed virus levels in multiple organs of the infected mice. A control group of mice received a dose of sterile saline solution in their nasal passages.

Kumar said that early in the pandemic, studies involving mice focused on the animals' lungs and did not assess whether the virus had invaded the brain. Kumars' team found that virus levels in the lungs of infected mice peaked three days after infection, then began to decline. However, very high levels of infectious virus were found in the brains of all the affected mice on the fifth and sixth days, which is when symptoms of severe disease became obvious, including labored breathing, disorientation and weakness.

The study found virus levels in the brain were about 1,000 times higher than in other parts of the body.

Kumar said the findings could help explain why some COVID-19 patients seem to be on the road to recovery, with improved lung function, only to rapidly relapse and die. His research and other studies suggest the severity of illness and the types of symptoms that different people experience could depend not only on how much virus a person was exposed to, but how it entered their body.

The nasal passages, he said, provide a more direct path to the brain than the mouth. And while the lungs of mice and humans are designed to fend off infections, the brain is ill equipped to do so, Kumar said. Once viral infections reach the brain, they trigger an inflammatory response that can persist indefinitely, causing ongoing damage.

"The brain is one of the regions where virus likes to hide," he said, because it cannot mount the kind of immune response that can clear viruses from other parts of the body.

"That's why we're seeing severe disease and all these multiple symptoms like heart disease, stroke and all these long-haulers with loss of smell, loss of taste," Kumar said. "All of this has to do with the brain rather than with the lungs."

Kumar said that COVID-19 survivors whose infections reached their brain are also at increased risk of future health problems, including auto-immune diseases, Parkinson's, multiple sclerosis and general cognitive decline.

"It's scary," Kumar said. "A lot of people think they got COVID and they recovered and now they're out of the woods. Now I feel like that's never going to be true. You may never be out of the woods."

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-19

HOUSTON - (Jan. 19, 2021) - Carbon nanotube fibers are not nearly as strong as the nanotubes they contain, but Rice University researchers are working to close the gap.

A computational model by materials theorist Boris Yakobson and his team at Rice's Brown School of Engineering establishes a universal scaling relationship between nanotube length and friction between them in a bundle, parameters that can be used to fine-tune fiber properties for strength.

The model is a tool for scientists and engineers who develop conductive fibers for aerospace, automotive, medical and textile applications like smart clothing. Carbon nanotube fibers have been considered as a possible basis for a space elevator, a project Yakobson has studied.

The research ...

2021-01-19

Scleroderma, a chronic and currently incurable orphan disease where tissue injury causes potentially lethal skin and lung scarring, remains poorly understood.

However, the defining characteristic of systemic sclerosis, the most serious form of scleroderma, is irreversible and progressive scarring that affects the skin and internal organs.

Published in iScience, Michigan Medicine's Scleroderma Program and the rheumatology and dermatology departments partnered with the Northwestern Scleroderma Program in Chicago and Mayo Clinic to investigate the causes of ...

2021-01-19

Researchers have revealed the first atomic structures of the respiratory apparatus that plants use to generate energy, according to a study published today in eLife.

The 3D structures of these large protein assemblies - the first described for any plant species - are a step towards being able to develop improved herbicides that target plant respiration. They could also aid the development of more effective pesticides, which target the pest's metabolism while avoiding harm to crops.

Most organisms use respiration to harvest energy from food. Plants use photosynthesis to convert sunlight into sugars, and then respiration to break down the sugars into energy. This involves tiny cell components called mitochondria and a set of five protein assemblies ...

2021-01-19

Provincial and territorial governments should set clear rules for vaccinating health care workers against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in public and private settings, and should not leave this task to employers, according to an analysis in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

"An effective vaccine provided to health care workers will protect both the health workforce and patients, reducing the overall burden of COVID-19 on services and ensuring adequate personnel to administer to people's health needs through the pandemic," writes Dr. Colleen M. Flood, University of Ottawa Research Chair in Health Law & Policy and a ...

2021-01-19

HAMILTON, ON, Jan. 19, 2021 -- McMaster researchers have developed a new form of cultivated meat using a method that promises more natural flavour and texture than other alternatives to traditional meat from animals.

Researchers Ravi Selvaganapathy and Alireza Shahin-Shamsabadi, both of the university's School of Biomedical Engineering, have devised a way to make meat by stacking thin sheets of cultivated muscle and fat cells grown together in a lab setting. The technique is adapted from a method used to grow tissue for human transplants.

The sheets of living cells, each about the thickness of a sheet of printer paper, are first grown in culture and then concentrated on growth plates before being peeled ...

2021-01-19

NANOTECHNOLOGY PREVENTS PREMATURE BIRTH IN MOUSE STUDIES

Media Contact: Rachel Butch, rbutch1@jhmi.edu

In a study in mice and human cells, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers say that they have developed a tiny, yet effective method for preventing premature birth. The vaginally delivered treatment contains nanosized (billionth of a meter) particles of drugs that easily penetrate the vaginal wall to reach the uterine muscles and prevent them from contracting. If proven effective in humans, the treatment could be one of the only clinical options available to prevent ...

2021-01-19

From a pair of simple principles of evolution--chance mutation and natural selection--nature has constructed an almost unfathomable richness of life around us. Despite our scientific sophistication, human design and engineering have struggled to emulate nature's techniques and her inexhaustible inventiveness. But that may be changing.

In a new perspective article, Stephanie Forrest and Risto Miikkulainen explore a domain known as evolutionary computation (EC), in which aspects of Darwinian evolution are simulated in computer systems.

The study highlights the progress our machines have made in replicating evolutionary processes and what this could mean for engineering design, software refinement, gaming strategy, robotics and even medicine, while fostering a deeper insight ...

2021-01-19

Using cutting-edge DNA sequencing technologies, a group of laboratories in Konstanz, Würzburg, Hamburg and Vienna, led by evolutionary biologist Professor Axel Meyer from the University of Konstanz, succeeded in fully sequencing the genome of the Australian lungfish. The genome, with a total size of more than 43 billion DNA building blocks, is nearly 14 times larger than that of humans and the largest animal genome sequenced to date. Its analysis provides valuable insights into the genetic and developmental evolutionary innovations that made it possible for fish to colonize land. The findings, published online in the journal Nature, expand our understanding of this major evolutionary ...

2021-01-19

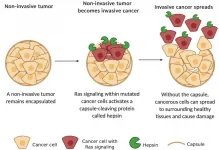

Researchers at the University of Helsinki have defined a cancer invasion machinery, which is orchestrated by a frequently mutated cancer gene called Ras. When signaling from Ras protein becomes abnormally high, like it does in many cancers, this switches on the cellular machinery that helps the cancer cells to depart from the tissue from which the cells have developed.

It has been unclear how the cancer invasion machinery works exactly, until now, as the study finds Ras in the role of Friar Lawrence in Shakespeare's famous play, "Get me an iron crow and bring it straight unto my cell (Romeo and Juliet, 5.2.21-23)." ...

2021-01-19

Climate change is more pronounced in the Arctic than anywhere else on the planet, raising concerns about the ability of wildlife to cope with the new conditions. A new study shows that rare insects are declining, suggesting that climatic changes may favour common species.

As part of a new volume of studies on the global insect decline, researchers are presenting the first Arctic insect population trends from a 24-year monitoring record of standardized insect abundance data from North-East Greenland.

The work took place during 1996-2018 as part of the ecosystem-based monitoring program Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring at the field station Zackenberg, located in the world's largest national ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Study finds COVID-19 attack on brain, not lungs, triggers severe disease in mice

The findings have implications for understanding the wide range in symptoms and severity of illness among humans who are infected by SARS-CoV-2