Researchers discover mechanism behind most severe cases of a common blood disorder

2021-01-19

(Press-News.org) With a name like glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, one would think it is a rare and obscure medical condition, but that's far from the truth. Roughly 400 million people worldwide live with potential of blood disorders due to the enzyme deficiency. While some people are asymptomatic, others suffer from jaundice, ruptured red blood cells and, in the worst cases, kidney failure.

Now, a team led by researchers at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have uncovered the elusive mechanism behind the most severe cases of the disease: a broken chain of amino acids that warps the shape of the condition's namesake protein, G6PD. The team, led by SLAC Professor Soichi Wakatsuki, report their findings January 18th in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

An essential enzyme

G6PD's role in our health is hard to overstate. In red blood cells, which deliver oxygen to other cells, the enzyme helps remove more chemically reactive and potentially harmful oxygen molecules, such as hydrogen peroxide, and convert them to water and other more inert byproducts. If the G6PD protein isn't working properly, red blood cells also stop working properly and can, in the worst cases, rupture.

"It's quite an important enzyme in our bodies," Wakatsuki said.

Still, doctors have mostly been at a loss to treat the disease, especially in the most severe cases, known as Class I. "At the moment the treatment for these patients is blood transfusions," said Stanford professor Daria Mochly-Rosen, a senior author on the new study.

Medical researchers have known for decades that upwards of 190 different mutations can lead to some forms of G6PD deficiency, and they also worked out the structure of ordinary G6PD in various forms decades ago. Mochly-Rosen and colleagues have also made strides in identifying drugs that may treat some less-severe forms of the disease, known as Class II and III.

Unfortunately, those drugs do not work for Class I cases, which have proved especially confusing. Most of the mutations that lead to the most severe symptoms were known to occur in areas far away from the active site where it binds to substrate molecules for its enzyme reactions - the usual spot where such mutations would be thought to cause problems.

A bend in the road

To better understand what was going on, Wakatsuki and colleagues from SLAC, Stanford University, the University of Tsukuba and the University de Concepción - along with a group of Stanford undergraduates and local high school students - started with X-ray crystallography studies of four forms of G6PD associated with the worst G6PD-deficiency symptoms, conducted at Structural Molecular Biology beamlines at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory's Advanced Lightsource and Argonne National Laboratory's Advanced Photon Source.

The team found that even though the mutations are far from G6PD's active site, they break up connections in a chain of amino acids that help stabilize the protein. That has a kind of domino effect on the whole protein molecule: It bends awkwardly, and a molecular arm that should help molecules bind to G6PD's active site instead wobbles unpredictably around. The team confirmed aspects of those results with a mixture of other techniques, including small angle X-ray scattering at Beam Line 4-2 at SSRL, computer simulations and cryogenic electron microscopy performed at the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Center.

The results show for the first time how the most severe cases of G6PD deficiency work at the molecular level and could help researchers design new drugs to treat the disease.

"It's been some time we've been working on this," Wakatsuki said. "There's no cure so far, but this could pave the way for new therapeutics."

Mochly-Rosen agreed. "You can start to imagine what kind of drug you need," she said. "With Class I, we were stuck until we found this clue."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. SSRL, ALS and APS are DOE Office of Science user facilities. The Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Center is also supported by the DOE Office of Science. The Structural Molecular Biology Program at SSRL is supported by the DOE Office of Science and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-19

WASHINGTON, January 19, 2021 -- What causes brain concussions? Is it direct translational or rotational impact? This is one of the research areas currently being explored by Qianhong Wu's lab at Villanova University.

Our brains consist of soft matter bathed in watery cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) inside a hard skull. An impact on the hard skull is transmitted through the thin layer of CSF within the subarachnoid space to the soft brain matter.

In Physics of Fluids, from AIP Publishing, Wu and co-authors Ji Lang and Rungun Nathan describe studying another system with the same features, an egg, to search for answers. An egg resembles the brain, because its soft yolk is bathed within a liquid egg white inside a hard shell.

Considering that in most concussive brain injuries, the skull does ...

2021-01-19

For the first time ever, a team of scientists, led by the University of Bristol, have described in detail a dinosaur's cloacal or vent - the all-purpose opening used for defecation, urination and breeding.

Although most mammals may have different openings for these functions, most vertebrate animals possess a cloaca.

Although we know now much about dinosaurs and their appearance as feathered, scaly and horned creatures and even which colours they sported, we have not known anything about how the vent appears.

Dr Jakob Vinther from the University of Bristol's School of Earth Sciences, along with colleagues Robert Nicholls, a palaeoartist, and Dr Diane Kelly, ...

2021-01-19

With a small snout, a short and curled tail, and a big, round stomach, mini pigs are the epitome of cute--and sometimes, they snore. Now, researchers think these snoring pigs can be used to study obstructive sleep apnea. A study appearing January 19 in the journal Heliyon found that obese Yucatan mini pigs do have naturally occurring sleep apnea and that MRI scans taken while they're in sedated sleep can be used to gain new insights into what happens in the airways during sleep apnea episodes via computational flow dynamic (CFD) analysis.

"These are very fat pigs," says first author Zi-Jun Liu, a research professor and principal investigator in the Department of Orthodontics ...

2021-01-19

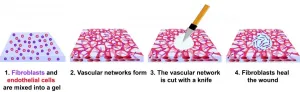

WASHINGTON, January 19, 2021 -- Biomedical engineers developed a technique to observe wound healing in real time, discovering a central role for cells known as fibroblasts. The work, reported in APL Bioengineering, by AIP Publishing, is the first demonstration of a wound closure model within human vascularized tissue in a petri dish.

Prior investigations of wound healing have used animal models, but healing in humans does not occur the same way. One difference is that wounds in mice and rats, for example, can heal without granulation tissue, a type of tissue critical to the healing of human wounds.

Granulation tissue forms after blood coagulates, and the wound scabs over. Coagulation creates a fibrin network that serves as a temporary matrix. Granulation tissue then takes over, ...

2021-01-19

WASHINGTON, January 19, 2021 -- The quest for ever-smaller electronic components led an international group of researchers to explore using molecular building blocks to create them. DNA is able to self-assemble into arbitrary structures, but the challenge with using these structures for nanoelectronic circuits is the DNA strands must be converted into highly conductive wires.

Inspired by previous works using the DNA molecule as a template for superconducting nanowires, the group took advantage of a recent bioengineering advance known as DNA origami to fold DNA into arbitrary shapes.

In AIP ...

2021-01-19

Youths with mood disorders who use and abuse cannabis (marijuana) have a higher risk for self-harm, death by all causes and death by unintentional overdose and homicide, according to research led by The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

Study findings are published in the JAMA Pediatrics.

"Marijuana use and addiction is common among youth and young adults with mood disorders, but the association of this behavior with self-harm, suicide and overall mortality risk is poorly understood in this already vulnerable population. These findings ...

2021-01-19

If you ever saw a honeybee hopping elegantly from flower to flower or avoiding you as you passed by, you may have wondered how such a tiny insect has such perfect navigation skills. These flying insects' skills are partially explained by the concept of optical flow: they perceive the speed with which objects move through their field of view. Robotics researchers have tried to mimic these strategies on flying robots, but with limited success. A team of TU Delft and the Westphalian University of Applied Sciences researchers therefore present an optical flow-based learning process that allows robots to estimate distances through the visual appearance (shape, color, texture) of the objects ...

2021-01-19

The older we grow, the weaker our muscles get, riddling old age with frailty and physical disability. But this doesn't only affect the individual, it also creates a significant burden on public healthcare. And yet, research efforts into the biological processes and biomarkers that define muscle aging have not yet defined the underlying causes.

Now, a team of scientists from lab of Johan Auwerx at EPFL's School of Life Sciences looked at the issue through a different angle: the similarities between muscle aging and degenerative muscle diseases. They have discovered protein aggregates that deposit in skeletal muscles during natural aging, and that blocking this can prevent the detrimental features of muscle ...

2021-01-19

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. -- Jan. 19, 2021 -- The results of a study led by Northern Arizona University and the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), an affiliate of City of Hope, suggest the immune systems of people infected with COVID-19 may rely on antibodies created during infections from earlier coronaviruses to help fight the disease.

COVID-19 isn't humanity's first encounter with a coronavirus, so named because of the corona, or crown-like, protein spikes on their surface. Before SARS-CoV-2 -- the virus that causes COVID-19 -- humans have navigated at least 6 other types of coronaviruses.

The study sought to understand how coronaviruses (CoVs) ignite the human immune system and conduct a deeper dive on the inner workings of the antibody response. The ...

2021-01-19

Researchers looked at neurons within the basal ganglia, a part of the brain that, when damaged, can severely impact a person's motor ability, making seemingly simple reaching-and-grasping tasks near impossible

They focused on a large group of neurons, which has two distinct types - D1 direct striatal output neurons and D2 indirect output neurons

These neurons are implicated in the development of Parkinson's and Huntington's - neurodegenerative diseases that result in the progressive degeneration or death of nerve cells

In this research, mice were trained to reach for and grasp a chocolate pellet, and optical methods were used to either excite or inhibit their D1 or D2 neurons

The researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers discover mechanism behind most severe cases of a common blood disorder