Researchers demonstrate snake venom evolution for defensive purposes

2021-01-21

(Press-News.org) Researchers from LSTM's Centre for Snakebite Research and Interventions (CSRI) have led an international team investigating the evolutionary origins of a novel defensive trait by snakes - venom spitting - and demonstrated that defensive selection pressures can influence venom composition in snakes in a repeatable manner.

In a paper published in the journal Science, the team, which includes authors from the UK, USA, Australia, the Netherlands, Spain, Norway, Brazil and Costa Rica, provide the first example of snake venom evolution being demonstrated to be associated with a role in defence, rather than the wide consensus that venom evolution is driven solely for prey capturing-ability.

LSTM's Dr. Taline Kazandjian is joint-first author on the paper. She said: "The evolution of adaptations is of fundamental importance in biology for understanding the processes by which organisms survive in their ecological niches. Venom systems are fantastic natural models for understanding the molecular basis of adaptations because there is a direct and measurable link between the genes associated with a trait, and the ecologically relevant phenotype, i.e. the venom activity and the consequences of that activity. Defence is not considered to be a strong selection pressure on the evolution of venom activity in snakes, however in this case we clearly demonstrate that defence can be a powerful influence on snake venom evolution."

The team used a variety of laboratory analyses to show that the three independent origins of venom spitting found in cobras and their near relatives corresponded with repeatable changes in venom composition in the three spitting lineages, thus demonstrating strong evidence of convergent evolution - i.e. that evolution has been repeatedly funnelled down the same pathway. The three different groups of spitting cobras were each found to have independently increased the production of PLA2 toxins for use for enhancing the defensive capabilities of their venom.

The researchers demonstrated that these increases in PLA2 toxins result in enhanced pain-causing ability of the venoms, by working synergistically with pre-existing "cytotoxins" found across all cobras, whether they spit their venom or not. The evolution of more potently painful venom likely enables spitting cobras to more effectively defend themselves from predators or aggressors by spitting venom into sensitive eyes, resulting in pain, inflammation and even blindness. That each independent lineage has evolved the same 'solution' for defence, represents an exemplary case of convergent evolution in the natural world.

Dr. Daniel Petras, a postdoctoral researcher at UCSD and joint-first author of the study said: "Through the combination of RNA sequencing, intact protein mass spectrometry and functional analysis of venom from the entire genus of cobras, we were able to identify a toxin class that is responsible for the pain inducing effect of the venom of spitting cobras. Excitingly, we showed that these toxins have evolved independently, yet convergently, in African and Asian spitting cobras."

Looking at why these three groups of closely related 'cobras' (note one is actually not a cobra, but a closely related cobra-like species called the rinkhals) are the only snakes that spit their venom, the team suggest this is likely due to two important preadaptations that are first required to enable the later inception and retention of venom spitting. First, cobras can raise the front third of their body up when hooding, which provides them with an ideal posture for defensively spitting venom at eyes. Second, cytotoxins existed in cobra venom before spitting ability evolved and these toxins likely caused initial low level pain, which was an important precursor to the advanced, highly painful, venom spitting trait seen today.

But what selective pressures stimulated the origin of defensive venom spitting in the first place? LSTM's Professor Nick Casewell, who led the study, explains: "While we cannot be sure, we make the argument that venom spitting is ideally suited to deterring attacks from our very own ancestors - hominins. Bipedal larger-brained hominins are likely to have posed a strong threat to snakes, and we show in this study that the evolutionary timing of the origin of venom spitting in Africa first, and then later in Asia, roughly corresponds with the divergence of our ancestors from chimps and bonobos in Africa, and our ancestors later migration to Asia. While further data is required to robustly test this hypothesis, its intriguing to think that human ancestors may have influenced the origin of this defensive chemical weapon in snakes".

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-21

Scientists have created a highly detailed map of skin, which reveals that cellular processes from development are re-activated in cells from patients with inflammatory skin disease. The researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, Newcastle University and Kings College London, discovered that skin from eczema and psoriasis patients share many of the same molecular pathways as developing skin cells. This offers potential new drug targets for treating these painful skin diseases.

Published on 22nd January in Science, the study also provides a completely new understanding of inflammatory disease, opening up new avenues for research on other inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Part of the global ...

2021-01-21

ITHACA, N.Y. - A streamlined process for awarding green cards to international STEM doctoral students graduating from U.S. universities could benefit American innovation and competitiveness, including leveling the field for startups eager to attract such highly skilled workers, according to a new study by researchers from Cornell University and the University of California, San Diego.

The new Biden administration backs policy reform aimed at achieving that end, which was part of bipartisan legislation proposed more than a decade ago. But progress has been stalled by broader concerns about visas ...

2021-01-21

LA JOLLA, CA--A big question on people's minds these days: how long does immunity to SARS-CoV-2 last following infection?

Now a research team from La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI), The University of Liverpool and the University of Southampton has uncovered an interesting clue. Their new study suggests that people with severe COVID-19 cases may be left with more of the protective "memory" T cells needed to fight reinfection.

"The data from this study suggest people with severe COVID-19 cases may have stronger long-term immunity," says study co-leader LJI Professor Pandurangan Vijayanand, M.D., Ph.D.

The research, published Jan. 21 in Science Immunology, is the first to describe the T cells that fight SARS-CoV-2 in "high resolution" ...

2021-01-21

Vaccinating people over 60 is the most effective way to mitigate mortality from COVID-19, a new age-based modeling study suggests. Although vaccination of younger adults is projected to avert the greatest incidence of disease, vaccinating older adults will most effectively reduce deaths, the analysis shows. Less than one year after SARS-CoV-2 was identified, deployment of multiple vaccines against the virus has been initiated in several countries. Although vaccine production is being rapidly scaled up, demand will exceed supply for the next several months. An urgent challenge is the optimization of vaccine allocation to maximize public health benefit. To quantify the impact of COVID-19 vaccine ...

2021-01-21

Vaccinating older adults for COVID-19 first will save substantially more U.S. lives than prioritizing other age groups, and the slower the vaccine rollout and more widespread the virus, the more critical it is to bring them to the front of the line.

That's one key takeaway from a new University of Colorado Boulder paper, published today in the journal Science, which uses mathematical modeling to make projections about how different distribution strategies would play out in countries around the globe.

The research has already informed policy recommendations by the Centers for Disease ...

2021-01-21

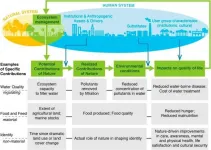

It is no secret that over the last few decades, humans have changed nature at an ever-increasing rate. A growing collection of research covers the many ways this is impacting our quality of life, from air quality to nutrition and income. To better understand how which areas are most at risk, scientists have combed through volumes of literature to present global trends in the relationship between human wellbeing and environmental degradation.

Their work, which included Fabrice DeClerck from the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, was summarized in "Global trends in nature's contributions to people", which was recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This systematic ...

2021-01-21

WASHINGTON, January 21, 2021 -- Despite cancer being a leading cause of death worldwide, treatment options for many types of cancers remain limited. This is partly due to the in vitro tools used to model cancers, which cannot adequately predict the behavior of a cancer or its sensitivity to drugs.

Further, animal models, like mice, biologically differ from humans in ways that play a critical role in immunotherapy, and results from animal studies do not always translate well to human disease.

These shortcomings point to a clear need for a better, patient-specific model to improve the understanding of cancer cells and their impacts.

Researchers from the University of Wisconsin and the University ...

2021-01-21

Medicated drops may help close small macular holes over a two- to eight-week period, allowing some people to avoid surgery to fix the vision problem, a new study suggests.

The findings, based on a retrospective multicenter case series published Dec. 15, 2020, in Ophthalmology Retina, could lead to a better understanding of which patients may benefit from the treatment, as well as the timeline of the treatment's effectiveness.

"For certain patients, medicated drops may heal their macular hole by decreasing inflammation and increasing fluid absorption in the retina," said ophthalmologist and retinal surgeon Dimitra Skondra, MD, PhD, senior author of the study. Skondra is an associate professor of ophthalmology and visual ...

2021-01-21

WASHINGTON, January 21, 2021 -- Cancer is a major, worldwide challenge, and its impact is projected to escalate due to aging and growth of the population. Researchers recognize that new approaches to diagnose and treat deadly cancers, including identifying new drugs to treat cancer, will be essential to curbing the growing impact of the disease.

While decades of investment in research have resulted in substantial improvements in surviving cancer, a key challenge remains in identifying new drugs that improve outcomes for cancer patients, particularly for cancers when tumors have spread throughout the body.

In APL Bioengineering, by AIP Publishing, researchers suggest a major hurdle to identifying new drugs is the paucity of models -- organisms ...

2021-01-21

EUGENE, Ore. -- Jan. 21, 2021 -- Developing economies suffer from a paradox: they don't receive investment flows from developed economies because they lack stability and high-quality financial and lawmaking institutions, but they can't develop those institutions without foreign funds.

A study co-authored by Brandon Julio, a professor in the Department of Finance at the University of Oregon's Lundquist College of Business, found that bilateral investment treaties, commonly known as BITs, can help developing economies overcome this paradox, but only as long as those ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers demonstrate snake venom evolution for defensive purposes