(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - There could be an intervention on the horizon to help prevent heart damage caused by the common chemotherapy drug doxorubicin, new research suggests.

Scientists found that this chemo drug, used to treat many types of solid tumors and blood cancers, is able to enter heart cells by hitchhiking on a specific type of protein that functions as a transporter to move a drug from the blood into heart cells.

By introducing another anti-cancer drug in advance of the chemo, the researchers were able to block the transporter protein, effectively stopping the delivery of doxorubicin to those cardiac cells. This added drug, nilotinib, has been previously found to inhibit activation of other, related transport proteins.

The current findings are based on lab experiments in cell cultures and mice. The researchers are continuing studies with hopes to start designing human trials of the drug intervention later in 2021.

"The proposed intervention strategy that we'd like to use in the clinic would be giving nilotinib before a chemotherapy treatment to restrict doxorubicin from accessing the heart," said first author Kevin Huang, who graduated in December from The Ohio State University with a PhD in pharmaceutical sciences. "We have pretty solid preclinical evidence that this intervention strategy might work."

The study is published today (Jan. 25, 2021) in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Doxorubicin has long been known for its potential to increase patients' risk for serious heart problems, with symptoms sometimes surfacing decades after chemo, but the mechanisms have been a mystery. The risk is dose-dependent - the more doses a patient receives, the higher the risk for cardiac dysfunction later in life that includes arrhythmia and a reduction in blood pumped with each contraction, a hallmark symptom of congestive heart failure.

Huang worked in the lab of senior study authors Shuiying Hu and Alex Sparreboom, faculty members in pharmaceutics and pharmacology and members of the Ohio State Comprehensive Cancer Center's Translational Therapeutics program. This research and other studies targeting different transport proteins to prevent chemo-related nerve pain were also part of Huang's dissertation.

"Our lab works on the belief that drugs don't naturally or spontaneously diffuse into any cell they would like to. We hypothesize that there are specialized protein channels found on specific cells that will facilitate movement of internal or external compounds into the cell," Huang said.

For this work, the team focused on cardiomyocytes, cells composing the muscle behind the heart contractions that pump blood to the rest of the body. The researchers examined cardiomyocytes that were reprogrammed from skin cells donated by two groups of cancer patients who had been treated with doxorubicin - some who suffered cardiac dysfunction after chemo, and others who did not.

The scientists found that the gene responsible for production of the transport protein in question, called OCT3, was highly expressed in the cells derived from cancer patients who had experienced heart problems after treatment with doxorubicin.

"We used mouse models and engineered cell models to demonstrate doxorubicin does transport through this protein channel, OCT3," Huang said. "We then looked prospectively into what this means from a therapy perspective."

Blocking OCT3 became the goal once researchers found that genetically modified mice lacking the OCT3 gene were protected from heart damage after receiving doxorubicin. Further studies showed that inhibiting OCT3 did not interfere with doxorubicin's effectiveness against cancer.

Hu and Sparreboom have specialized in a class of drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which block specific enzymes related to many cell functions. Nilotinib, a chronic myeloid leukemia drug, is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is also known to act on OCT3.

Additional experiments showed that cardiac function was preserved in mice that were pretreated with nilotinib before receiving doxorubicin - and the pretreatment did not interfere with doxorubicin's ability to kill cancer cells.

The researchers plan to gather additional supporting evidence before pursuing a Phase 1 clinical trial testing the safety of two components of the proposed drug intervention in humans: blocking the function of the OCT3 transporter protein and demonstrating that inhibiting OCT3 in patients treated with doxorubicin protects those patients' hearts from chemo-induced injury.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Robert Bosch Stiftung, the German Research Foundation and Pelotonia funds from Ohio State. Huang was named a Pelotonia Graduate Fellow in 2018.

Additional Ohio State co-authors include Megan Zavorka Thomas, Eric Eisenmann, Muhammad Erfan Uddin, Duncan DiGiacomo, Alexander Pan, Sherry Xia, Yang Li, Yan Jin, Qiang Fu, Alice Gibson, Ingrid Bonilla, Cynthia Carnes, Kara Corps, Vincenzo Coppola, Sakima Smith, Daniel Addison, Ralf Bundschuh, Maryam Lustberg, Moray Campbell, Pearlly Yan and Sharyn Baker.

Contacts:

Kevin Huang,

Huang.2834@osu.edu

Alex Sparreboom,

Sparreboom.1@osu.edu

Written By Emily Caldwell,

Caldwell.151@osu.edu

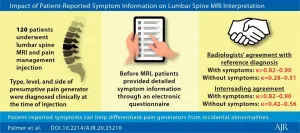

Leesburg, VA, January 25, 2021--According to an open-access article in ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), in lumbar spine MRI, presumptive pain generators diagnosed using symptom information from brief electronic questionnaires showed almost perfect agreement with pain generators diagnosed using symptom information from direct patient interviews.

"Using patient-reported symptom information from a questionnaire, radiologists interpreting lumbar spine MRI converged on diagnoses of presumptive pain generators and distinguished these from incidental abnormalities," wrote Rene Balza of the ...

Restricting eating to an eight-hour window, when activity is highest, decreased the risk of development, growth and metastasis of breast cancer in mouse models, report researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, Moores Cancer Center and Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System (VASDSH).

The findings, published in the January 25, 2021 edition of Nature Communications, show that time-restricted feeding -- a form of intermittent fasting aligned with circadian rhythms -- improved metabolic health and tumor circadian rhythms in mice with obesity-driven postmenopausal breast cancer.

"Previous research has shown that obesity increases the risk of a variety of cancers by negatively affecting how the body ...

Corals, like all animals, must eat to live. The problem is that most corals grow in tropical waters that are poor in nutrients, sort of like ocean deserts; it's this lack of nutrients that makes the water around coral reefs so crystal clear. Because food is not readily available, corals have developed a remarkable feeding mechanism that involves a symbiotic relationship with single-celled algae. These algae grow inside the corals, using the coral tissue as shelter and absorbing the CO2 that the corals produce. In exchange, the algae provide corals with nutrients they produce through photosynthesis. These algae contain a variety of pigments, which give the coral reefs the ...

Scientists conducted the first study to examine the fetal health impact of light pollution based on a direct measure of skyglow, an important aspect of light pollution. Using an empirical regularity discovered in physics, called Walker's Law, a team from Lehigh University, Lafayette College and the University of Colorado Denver in the U.S., found evidence of reduced birth weight, shortened gestational length and preterm births.

Specifically, the likelihood of a preterm birth could increase by approximately 1.48 percentage points (or 12.9%), according to the researchers, as a result of increased nighttime brightness. Nighttime brightness is characterized by being able to see only one-fourth ...

WASHINGTON (Jan. 25, 2021) - The majority of dermatology patients surveyed find telehealth appointments to be a suitable alternative to in-person office visits, according to a survey study from researchers at the George Washington University (GW) Department of Dermatology. The results are published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed many aspects of everyday life, including how patients interact with the health care system and seek medical care. Social distancing and stay-at-home orders have led to a move from in-office to virtual visits. While many specialties had to shift to the virtual format because ...

The Special Issue, Volume 10, of Inter Faculty takes up the theme of resonance in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic and its ensuing societal shifts. For, the pandemic this year (2020) reminded us more than ever that we live in 'VUCA' - volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. Many things that used to be taken for granted up until a year ago crumbled abruptly and globally. The pandemic struck many aspects or our societies such as public health, economy and social bonds thereby uncovering the vulnerability of the modern society. Universities are no exception to this. Just as one nation by itself cannot tackle these global challenges, neither can these challenges be solved ...

Using machine learning, researchers at the UC Davis MIND Institute have identified several patterns of maternal autoantibodies highly associated with the diagnosis and severity of autism.

Their study, published Jan. 22 in Molecular Psychiatry, specifically focused on maternal autoantibody-related autism spectrum disorder (MAR ASD), a condition accounting for around 20% of all autism cases.

"The implications from this study are tremendous," said Judy Van de Water, a professor of rheumatology, allergy and clinical immunology at UC Davis and the lead author of the study. "It's the first time that machine learning has been used to identify with 100% accuracy MAR ASD-specific patterns as potential biomarkers of ASD risk."

Autoantibodies are immune proteins ...

Irvine, Calif., Jan. 25, 2021 -- Scientists at the University of California, Irvine and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory have for the first time quantified how warming coastal waters are impacting individual glaciers in Greenland's fjords. Their work is the subject of a study published recently in Science Advances.

Working under the auspices of the Oceans Melting Greenland mission for the past five years, the researchers used ships and aircraft to survey 226 glaciers in all sectors of one of Earth's largest islands. They found that 74 glaciers situated in deep, steep-walled valleys accounted for nearly half of Greenland's total ice loss between 1992 and 2017.

Such fjord-bound glaciers were discovered to be the ...

Epilepsy, a neurological disease that causes recurring seizures with a wide array of effects, impacts approximately 50 million people across the world. This condition has been recognized for a long time -- written records of epileptic symptoms date all the way back to 4000 B.C.E. But despite this long history of knowledge and treatment, the exact processes that occur in the brain during a seizure remain elusive.

Scientists have observed distinctive patterns in the electrical activity of neuron groups in healthy brains. Networks of neurons move through states of similar behavior (synchronization) and dissimilar behavior (desynchronization) ...

A new study demonstrates that antibodies generated by the novel coronavirus react to other strains of coronavirus and vice versa, according to research published today by scientists from Oregon Health & Science University.

However, antibodies generated by the SARS outbreak of 2003 had only limited effectiveness in neutralizing the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Antibodies are blood proteins that are made by the immune system to protect against infection, in this case by a coronavirus.

The study published today in the journal Cell Reports.

"Our finding has some important implications concerning immunity toward different strains of coronavirus infections, ...