(Press-News.org) Members of Syracuse University's College of Arts and Sciences are shining new light on an enduring mystery--one that is millions of years in the making.

A team of paleontologists led by Professor Cathryn Newton has increased scientists' understanding of whether Devonian marine faunas, whose fossils are lodged in a unit of bedrock in Central New York known as the Hamilton Group, were stable for millions of years before succumbing to waves of extinctions.

Drawing on 15 years of quantitative analysis with fellow professor Jim Brower (who died in 2018), Newton has continued to probe the structure of these ancient fossil communities, among the most renowned on Earth.

The group's findings, reported by the Geological Society of America (GSA), provide critical new evidence for the unusual, long-term stability of these Devonian period communities.

Such persistence, Newton says, is a longstanding scientific enigma. She and her colleagues tested the hypothesis that these ancient communities displayed coordinated stasis--a theory that attempts to explain the emergence and disappearance of species across geologic time.

Newton and Brower, along with their student Willis Newman G'93, found that Devonian marine communities vary more in species composition than the theory predicts. Newton points out that they sought not to disprove coordinated stasis but rather to gain a more sophisticated understanding of when it is applicable. "Discovering more about the dynamics of these apparently stable Devonian communities is critical," she says. "Such knowledge has immediate significance for marine community changes in our rapidly warming seas."

Since geologist James Hall Jr. first published a series of volumes on the region's Devonian fossils and strata in the 1840s, the Hamilton Group has become a magnet for research scientists and amateur collectors alike. Today, Central New York is frequently used to test new ideas about large-scale changes in Earth's organisms and environments.

During Middle Devonian time (approximately 380-390 million years ago), the faunal composition of the region changed little over 4-6 million years. "It's a significant amount for marine invertebrate communities to remain stable, or 'locked,'" explains Newton, a professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

She, Brower and student researchers spent years examining eight communities of animals that once dwelled in a warm, shallow sea on the northern rim of the Appalachian Basin (which, eons ago, lay south of the equator). When the organisms died, sediment from the seafloor began covering their shells and exoskeletons. Minerals from the sediment gradually seeped into their remains, causing them to fossilize. The process also preserved many of them in living position, conserving original shell materials at some sites.

These fossils currently populate exposed bedrock throughout Central New York, ranging from soft, dark, deep-water shale to hard, species-rich, shelf siltstone. "Communities near the top of the bedrock exhibit more taxonomic and ecological diversity than those at the bottom," Newton says. "We can compare the community types and composition through time. They are remarkable sites."

Coordinated stasis has been a source of contention since 1995, when it was introduced. At the center of the dispute are two model-based explanations: environmental tracking and ecological locking.

Environmental tracking suggests that faunas follow their environment. "Here, periods of relative stasis are flanked by coordinated extinctions or regional disappearances. When the environment changes, so do marine faunas," says Newton, also Professor of Interdisciplinary Sciences and Dean Emerita of Arts and Sciences.

Ecological locking, in contrast, views marine faunas as tightly structured communities, resistant to large-scale taxonomic change. Traditionally, this model has been used to describe the stability of lower Hamilton faunas.

Newton and her colleagues analyzed more than 80 sample sites, each containing some 300 specimens. Special emphasis was placed on the Cardiff and Pecksport Members, two rock formations in the Finger Lakes region that are part of the ancient Marcellus subgroup, famed for its natural gas reserves.

"We found that lower Hamilton faunas, with two exceptions, do not have clear counterparts among upper ones. Therefore, our quantitative tests do not support the ecological locking model as an explanation for community stability in these faunas," she continues.

Newton considers this project a final tribute to Newman, a professor of biology at the State University of New York at Cortland, who died in 2014, and Brower, who fell seriously ill while the manuscript was being finalized. "Jim knew that he likely would not live to see its publication," says Newton, adding that Brower died as the paper was submitted to GSA.

She says this new work extends and, in some ways, completes the team's earlier research by further analyzing community structures in the Marcellus subgroup. "It has the potential to change how scientists view long-term stability in ecological communities."

INFORMATION:

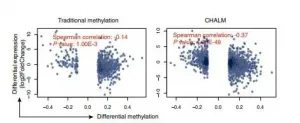

Irvine, CA - January 27, 2021 - A new University of California, Irvine-led study finds a new method for identifying biomarkers may aid in early cancer diagnosis. The study focused on lung cancer, however the Cell Heterogeneity-Adjusted cLonal Methylation (CHALM) method has been tested on aging and Alzheimer's diseases as well and is expected to be effective for studying other diseases.

"We found the CHALM method may be a valuable tool in helping researchers to identify more reliable differentially methylated genes from sequence-based methylation data," ...

Doctors are increasingly using genetic signatures to diagnose diseases and determine the best course of care, but using DNA sequencing and other techniques to detect genomic rearrangements remains costly or limited in capabilities. However, an innovative breakthrough developed by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and the VCU Department of Physics promises to diagnose DNA rearrangement mutations at a fraction of the cost with improved accuracy.

Led by VCU physicist Jason Reed, Ph.D., the team developed a technique that combines a process called digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) with high-speed atomic force microscopy (HSAFM) to create an image with such nanoscale resolution that users can measure differences in ...

Historically redlined neighborhoods are more likely to have a paucity of greenspace today compared to other neighborhoods. The study by researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and the University of California, Berkeley and San Francisco, demonstrates the lasting effects of redlining, a racist mortgage appraisal practice of the 1930s that established and exacerbated racial residential segregation in the United States. Results appear in Environmental Health Perspectives.

In the 1930s, the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) assigned risk grades to neighborhoods across the country based on racial demographics and other factors. "Hazardous" areas--often those whose residents included people ...

LAWRENCE -- For at least a century, ecologists have wondered at the tendency for populations of different species to cycle up and down in steady, rhythmic patterns.

"These cycles can be really exaggerated -- really huge booms and huge busts -- and quite regular," said Daniel Reuman, professor of ecology & evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas and senior scientist at the Kansas Biological Survey. "It attracted people's attention because it was kind of mysterious. Why would such a big thing be happening?"

A second observation in animal populations ...

(Boston)--Researchers from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have identified proteins that are essential for the viability of whole genome doubled tumor cells, yet non-essential to normal cells that comprise the majority of human tissue.

"Exploiting these vulnerabilities represents a highly significant and currently untapped opportunity for therapeutic intervention, particularly because whole genome doubling is a distinguishing characteristic of many tumor types," said corresponding author Neil J. Ganem, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology and medicine, section of hematology and medical oncology, at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM).

The vast majority of human cells are diploid, meaning that they possess two copies of each ...

The Asia Pacific Consortium on Osteoporosis (APCO) has today launched the first pan-Asia Pacific clinical practice standards for the screening, diagnosis, and management of osteoporosis, targeting a broad range of high-risk groups.

Published in Osteoporosis International today, 'The APCO Framework' comprises 16 minimum clinical standards set to serve as a benchmark for the provision of optimal osteoporosis care in the region.

Developed by APCO members representing key osteoporosis stakeholders, and multiple medical and surgical specialities, this set of clear, concise, relevant and pragmatic clinical standards aims to support national societies, guidelines development authorities, and health care policy makers with ...

People who take opioid medications for chronic pain may have a hard time finding a new primary care clinic that will take them on as a patient if they need one, according to a new "secret shopper" study of hundreds of clinics in states across the country.

Stigma against long-term users of prescription opioids, likely related to the prospect of taking on a patient who might have an opioid use disorder or addiction, appears to play a role, the University of Michigan research suggests.

Simulated patients who said their doctor or other primary care provider had retired were more likely to be told they could be accepted as new patients, compared with those who said their provider had stopped prescribing opioids to them for an unknown reason.

The U-M primary care provider ...

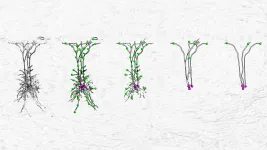

Neurons, the fundamental units of the brain, are complex computers by themselves. They receive input signals on a tree-like structure - the dendrite. This structure does more than simply collect the input signals: it integrates and compares them to find those special combinations that are important for the neurons' role in the brain. Moreover, the dendrites of neurons come in a variety of shapes and forms, indicating that distinct neurons may have separate roles in the brain.

A simple yet faithful model

In neuroscience, there has historically been a tradeoff between a model's faithfulness to the underlying biological neuron and its complexity. Neuroscientists have constructed ...

Being constantly flooded by a mass of stimuli, it is impossible for us to react to all of them. The same holds true for a little fish. Which stimuli should it pay attention to and which not? Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology have now deciphered the neuronal circuit that zebrafish use to prioritize visual stimuli. Surrounded by predators, a fish can thus choose its escape route from this predicament.

Even though we are not exposed to predators, we still have to decide which stimuli we pay attention to - for example, when crossing a street. Which cars should we avoid, which ones can we ignore?

"The ...

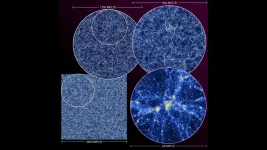

A massive simulation of the cosmos and a nod to the next generation of computing

A team of physicists and computer scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory performed one of the five largest cosmological simulations ever. Data from the simulation will inform sky maps to aid leading large-scale cosmological experiments.

The simulation, called the Last Journey, follows the distribution of mass across the universe over time -- in other words, how gravity causes a mysterious invisible substance called "dark matter" to clump ...