(Press-News.org) INDIANAPOLIS--Researchers at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center have identified how breast cancer cells hide from immune cells to stay alive. The discovery could lead to better immunotherapy treatment for patients.

Xinna Zhang, PhD, and colleagues found that when breast cancer cells have an increased level of a protein called MAL2 on the cell surface, the cancer cells can evade immune attacks and continue to grow. The findings are published this month in The Journal of Clinical Investigation and featured on the journal's cover.

The lead author of the study, Zhang is a member of the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center and assistant professor of medical and molecular genetics at IU School of Medicine.

Considered the future of cancer treatment, immunotherapy harnesses the body's immune system to target and destroy cancer cells. Understanding how cancer cells avoid immune attacks could offer new ways to improve immunotherapy for patients, explained Xiongbin Lu, PhD, Vera Bradley Foundation Professor of Breast Cancer Innovation and cancer center researcher.

"Current cancer immunotherapy has wonderful results in some patients, but more than 70% of breast cancer patients do not respond to cancer immunotherapy," Lu said. "One of the biggest reasons is that tumors develop a mechanism to evade the immune attacks."

The collaborative research team set out to answer key questions: How do breast cancer cells develop this immune evasion mechanism, and could targeting that action lead to improved immunotherapies?

Zhang and Lu, members of the Vera Bradley Foundation Center for Breast Cancer Research, turned to biomedical data researcher Chi Zhang, PhD, assistant professor of medical and molecular genetics at IU School of Medicine. Chi Zhang developed a computational method to analyze data sets from more than 1,000 breast cancer patients through The Cancer Genome Atlas. That analysis led researchers to MAL2; it showed that higher levels of MAL2 in breast cancer, and especially in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), was linked to poorer patient survival.

"Dr. Chi Zhang used his advanced computational tool to build a bridge that connects cancer genetics and cancer genomics with a clinical outcome," Lu said. "We can analyze molecular features from thousands of breast tumor samples to identify potential targets for cancer immunotherapy. From that data, MAL2 was the top-ranked gene that we wanted to study."

Xinna Zhang took that data to her lab to determine MAL2's purpose in the cells, how it affects breast cancer cell growth and how it interacts with immune cells. Using breast cancer tissue samples from IU patients, cell models and animal models, she found that breast cancer cells express more MAL2 than normal cells. She also discovered that high levels of MAL2 significantly enhanced tumor growth, while inhibiting the protein can almost completely stop tumor growth.

In Lu's lab, he used a three-dimensional, patient-derived model called an organoid to better understand how reducing MAL2 could improve patient outcomes.

"Tumor cells can evade immune attacks; with less MAL2, the cancer cells can be recognized and killed by the immune system," Lu said. "MAL2 is a novel target. By identifying its function in cancer cells and cancer immunology, we now know its potential as a cancer immunology target."

INFORMATION:

Researchers now are exploring ways these findings could be used to develop and improve breast cancer therapies.

Lu is co-leading a cancer immunotherapy program for triple negative breast cancer as part of the Indiana University Precision Health Initiative. Both Xinna Zhang and Chi Zhang are also involved in the initiative for developing novel breast cancer immunotherapy. The Precision Health Initiative, the first recipient of funding from the Indiana University Grand Challenges Program, is enhancing the prevention, treatment, and health outcomes of human diseases through a more precise analysis of genetic, developmental, behavioral and environmental factors that shape an individual's health.

Additional authors are Bryan P. Schneider, MD, Yunlong Liu, PhD, and Sha Cao, PhD, of IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center; Yuanzhang Fang, PhD, Lifei Wang, Changlin Wan, Yifan Sun, Kevin Van der Jeught, PhD, Zhuolong Zhou, PhD, Tianhan Dong, Ka Man So, Tao Yu, PhD, Yujing Li, PhD, Haniyeh Eyvani, Austyn B. Colter, Edward Dong, George E. Sandusky, PhD, of IU School of Medicine; and Jin Wang, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine.

This study was supported by the Vera Bradley Foundation for Breast Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant, and the National Institutes of Health (R01CA203737 and R01CA206366).

Members of Syracuse University's College of Arts and Sciences are shining new light on an enduring mystery--one that is millions of years in the making.

A team of paleontologists led by Professor Cathryn Newton has increased scientists' understanding of whether Devonian marine faunas, whose fossils are lodged in a unit of bedrock in Central New York known as the Hamilton Group, were stable for millions of years before succumbing to waves of extinctions.

Drawing on 15 years of quantitative analysis with fellow professor Jim Brower (who died in 2018), Newton has continued to probe the structure of these ancient fossil communities, among the most renowned on Earth.

The group's findings, reported by the Geological Society of America (GSA), provide critical ...

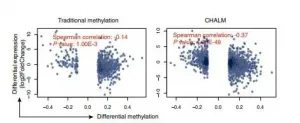

Irvine, CA - January 27, 2021 - A new University of California, Irvine-led study finds a new method for identifying biomarkers may aid in early cancer diagnosis. The study focused on lung cancer, however the Cell Heterogeneity-Adjusted cLonal Methylation (CHALM) method has been tested on aging and Alzheimer's diseases as well and is expected to be effective for studying other diseases.

"We found the CHALM method may be a valuable tool in helping researchers to identify more reliable differentially methylated genes from sequence-based methylation data," ...

Doctors are increasingly using genetic signatures to diagnose diseases and determine the best course of care, but using DNA sequencing and other techniques to detect genomic rearrangements remains costly or limited in capabilities. However, an innovative breakthrough developed by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and the VCU Department of Physics promises to diagnose DNA rearrangement mutations at a fraction of the cost with improved accuracy.

Led by VCU physicist Jason Reed, Ph.D., the team developed a technique that combines a process called digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) with high-speed atomic force microscopy (HSAFM) to create an image with such nanoscale resolution that users can measure differences in ...

Historically redlined neighborhoods are more likely to have a paucity of greenspace today compared to other neighborhoods. The study by researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and the University of California, Berkeley and San Francisco, demonstrates the lasting effects of redlining, a racist mortgage appraisal practice of the 1930s that established and exacerbated racial residential segregation in the United States. Results appear in Environmental Health Perspectives.

In the 1930s, the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) assigned risk grades to neighborhoods across the country based on racial demographics and other factors. "Hazardous" areas--often those whose residents included people ...

LAWRENCE -- For at least a century, ecologists have wondered at the tendency for populations of different species to cycle up and down in steady, rhythmic patterns.

"These cycles can be really exaggerated -- really huge booms and huge busts -- and quite regular," said Daniel Reuman, professor of ecology & evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas and senior scientist at the Kansas Biological Survey. "It attracted people's attention because it was kind of mysterious. Why would such a big thing be happening?"

A second observation in animal populations ...

(Boston)--Researchers from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have identified proteins that are essential for the viability of whole genome doubled tumor cells, yet non-essential to normal cells that comprise the majority of human tissue.

"Exploiting these vulnerabilities represents a highly significant and currently untapped opportunity for therapeutic intervention, particularly because whole genome doubling is a distinguishing characteristic of many tumor types," said corresponding author Neil J. Ganem, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology and medicine, section of hematology and medical oncology, at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM).

The vast majority of human cells are diploid, meaning that they possess two copies of each ...

The Asia Pacific Consortium on Osteoporosis (APCO) has today launched the first pan-Asia Pacific clinical practice standards for the screening, diagnosis, and management of osteoporosis, targeting a broad range of high-risk groups.

Published in Osteoporosis International today, 'The APCO Framework' comprises 16 minimum clinical standards set to serve as a benchmark for the provision of optimal osteoporosis care in the region.

Developed by APCO members representing key osteoporosis stakeholders, and multiple medical and surgical specialities, this set of clear, concise, relevant and pragmatic clinical standards aims to support national societies, guidelines development authorities, and health care policy makers with ...

People who take opioid medications for chronic pain may have a hard time finding a new primary care clinic that will take them on as a patient if they need one, according to a new "secret shopper" study of hundreds of clinics in states across the country.

Stigma against long-term users of prescription opioids, likely related to the prospect of taking on a patient who might have an opioid use disorder or addiction, appears to play a role, the University of Michigan research suggests.

Simulated patients who said their doctor or other primary care provider had retired were more likely to be told they could be accepted as new patients, compared with those who said their provider had stopped prescribing opioids to them for an unknown reason.

The U-M primary care provider ...

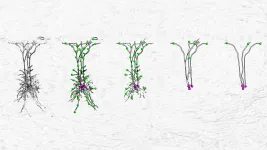

Neurons, the fundamental units of the brain, are complex computers by themselves. They receive input signals on a tree-like structure - the dendrite. This structure does more than simply collect the input signals: it integrates and compares them to find those special combinations that are important for the neurons' role in the brain. Moreover, the dendrites of neurons come in a variety of shapes and forms, indicating that distinct neurons may have separate roles in the brain.

A simple yet faithful model

In neuroscience, there has historically been a tradeoff between a model's faithfulness to the underlying biological neuron and its complexity. Neuroscientists have constructed ...

Being constantly flooded by a mass of stimuli, it is impossible for us to react to all of them. The same holds true for a little fish. Which stimuli should it pay attention to and which not? Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology have now deciphered the neuronal circuit that zebrafish use to prioritize visual stimuli. Surrounded by predators, a fish can thus choose its escape route from this predicament.

Even though we are not exposed to predators, we still have to decide which stimuli we pay attention to - for example, when crossing a street. Which cars should we avoid, which ones can we ignore?

"The ...