(Press-News.org) To survive the open ocean, tiny fish larvae, freshly hatched from eggs, must find food, avoid predators, and navigate ocean currents to their adult habitats. But what the larvae of most marine species experience during these great ocean odysseys has long been a mystery, until now.

A team of scientists from NOAA's Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, the University of Hawai'i (UH) at Mānoa, Arizona State University and elsewhere have discovered that a diverse array of marine animals find refuge in so-called 'surface slicks' in Hawai'i. These ocean features create a superhighway of nursery habitat for more than 100 species of commercially and ecologically important fishes, such as mahi-mahi, jacks, and billfish. Their findings were published today in the journal Scientific Reports.

Surface slicks are meandering lines of smooth surface water formed by the convergence of ocean currents, tides, and variations in the seafloor and have long been recognized as an important part of the seascape. The traditional Hawaiian mele (song) Kona Kai `?pua describes slicks as Ke kai ma`oki`oki, or "the streaked sea" in the peaceful seas of Kona. Despite this historical knowledge and scientists' belief that slicks are important for fish, the tiny marine life that slicks contain has remained elusive.

To unravel the slicks' secrets, the research team conducted more than 130 plankton net tows inside the surface slicks and surrounding waters along the leeward coast of Hawai'i Island, while studying ocean properties. In these areas, they searched for larvae and other plankton that live close to the surface. They then combined those in-water surveys with a new technique to remotely sense slick footprints using satellites.

A DIVERSE MARINE NURSERY

Though the slicks only covered around 8% of the ocean surface in the 380-square-mile-study area, they contained an astounding 39% of the study area's surface-dwelling larval fish; more than 25% of its zooplankton, which the larval fish eat; and 75% of its floating organic debris such as feathers and leaves.

Larval fish densities in surface slicks off West Hawai?i were, on average, over 7 times higher than densities in the surrounding waters.

The study showed that surface slicks function as a nursery habitat for marine larvae of at least 112 species of commercially and ecologically important fishes, as well as many other animals. These include coral reef fishes, such as jacks, triggerfish and goatfish; pelagic predators, for example mahi-mahi; deep-water fishes, such as lanternfish; and various invertebrates, such as snails, crabs, and shrimp.

The remarkable diversity of fishes found in slick nurseries represents nearly 10% of all fish species recorded in Hawai?i. The total number of taxa in the slicks was twice that found in the surrounding surface waters, and many fish taxa were between 10 and 100 times more abundant in slicks.

"We were shocked to find larvae of so many species, and even entire families of fishes, that were only found in surface slicks," said lead author Dr. Jonathan Whitney, marine ecologist at NOAA, former postdoctoral fellow at the Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research (JIMAR) in UH Mānoa's School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST). "This suggests they are dependent on these essential habitats."

AN INTERCONNECTED SUPERHIGHWAY

"These 'bioslicks' form an interconnected superhighway of rich nursery habitat that accumulate and attract tons of young fishes, along with dense concentrations of food and shelter," said Whitney. "The fact that surface slicks host such a large proportion of larvae, along with the resources they need to survive, tells us they are critical for the replenishment of adult fish populations."

In addition to providing crucial nursing habitat for various species and helping maintain healthy and resilient coral reefs, slicks create foraging hotspots for larval fish predators and form a bridge between coral reef and pelagic ecosystems.

What's more, the slicks host larvae and juvenile stages of many forage fishes like flying fishes that are critical to pelagic food webs.

"These hotspots provide more food at the base of the food chain that amplifies energy up to top predators," said study co-author Dr. Jamison Gove, a research oceanographer for NOAA. "This ultimately enhances fisheries and ecosystem productivity."

CONCENTRATING DEBRIS

While slicks may seem like havens for all tiny marine animals, there's a hidden hazard lurking in these ocean oases: plastic debris. Within the study area, 95% of the plastic debris collected into slicks, compared with 75% of the floating organic debris. Larvae may get some shelter from plastic debris, but it comes at the cost of chemical exposure and incidental ingestion.

"Until we stop plastics from entering the ocean," Whitney said, "the accumulation of hazardous plastic debris in these nursery habitats remains a serious threat to the biodiversity hosted here."

A BROAD IMPACT

In certain areas, slicks can be dominant surface features, and the new research shows these conspicuous phenomena hold more ecological value than meets the eye.

"Our work illustrates how these oceanic features (and animals' behavioral attraction to them) impact the entire surface community, with implications for the replenishment of adults that are important to humans for fisheries, recreation, and other ecosystem services," said Dr. Margaret McManus, co-author, Professor and Chair of the Department of Oceanography at UH Mānoa. "These findings will have a broad impact, changing the way we think about oceanic features as pelagic nurseries for ocean fishes and invertebrates."

INFORMATION:

The Institute for Scientific Information on Coffee (ISIC) published a new report today, titled 'Coffee and sleep in everyday lives', authored by Professor Renata Riha, from the Department of Sleep Medicine at the University of Edinburgh. It reviews the latest research into coffee's effect on sleep and suggests that while drinking coffee early in the day can help support alertness and concentration levels1, especially when sleep patterns are disturbed; decreasing intake six hours before bedtime may help reduce its impact on sleep2.

Coffee is largely consumed daily for the pleasure of its taste3, as well as its beneficial effect on wakefulness and concentration (due to its caffeine content)4. ...

A new study further highlighting a potential physiological cause of clinical depression could guide future treatment options for this serious mental health disorder. Published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, researchers show differences between the cellular composition of the brain in depressed adults who died by suicide and non-psychiatric individuals who died suddenly by other means.

"We found a reduced number of astrocytes, highlighted by staining the protein vimentin, in many regions of the brain in depressed adults," reports Naguib Mechawar, a Professor at the Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Canada, and senior author of this article. ...

Researchers from University of Notre Dame, York University (Canada), and University of New England (Australia) published a new paper in the Journal of Marketing that identifies a novel reason why people under-save and demonstrates a simple, short, and inexpensive intervention that increases intentions to save and actual savings.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled "Popping the Positive Illusion of Financial Responsibility Can Increase Personal Savings: Applications in Emerging and Western Markets" and is authored by Emily Garbinsky, Nicole Mead, and Daniel Gregg.

People around the world are not saving enough money. Since increasing ...

WASHINGTON--The start of California's annual rainy season has been pushed back from November to December, prolonging the state's increasingly destructive wildfire season by nearly a month, according to new research. The study cannot confirm the shift is connected to climate change, but the results are consistent with climate models that predict drier autumns for California in a warming climate, according to the authors.

Wildfires can occur at any time in California, but fires typically burn from May through October, when the state is in its dry season. The start of the rainy season, historically in November, ends wildfire season as plants become too moist to burn.

California's rainy season has been starting progressively later in recent decades and climate ...

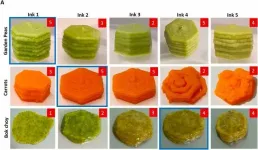

Researchers from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore), Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH) have developed a new way to create "food inks" from fresh and frozen vegetables, that preserves their nutrition and flavour better than existing methods.

Food inks are usually made from pureed foods in liquid or semi-solid form, then 3D-printed by extrusion from a nozzle, and assembled layer by layer.

Pureed foods are usually served to patients suffering from swallowing difficulties known as dysphagia. To present the ...

Politicians around the world must be held to account for mishandling the covid-19 pandemic, argues a senior editor at The BMJ today.

Executive editor, Dr Kamran Abbasi, argues that at the very least, covid-19 might be classified as 'social murder' that requires redress.

Today 'social murder' may describe a lack of political attention to the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age that exacerbate the pandemic.

When politicians and experts say that they are willing to allow tens of thousands of premature deaths, for the sake of population immunity or in the hope of propping up the economy, is that not premeditated ...

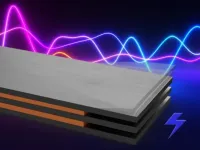

Piezoelectric materials hold great promise as sensors and as energy harvesters but are normally much less effective at high temperatures, limiting their use in environments such as engines or space exploration. However, a new piezoelectric device developed by a team of researchers from Penn State and QorTek remains highly effective at elevated temperatures.

Clive Randall, director of Penn State's Materials Research Institute (MRI), developed the material and device in partnership with researchers from QorTek, a State College, Pennsylvania-based company specializing in smart material devices and high-density power electronics.

"NASA's need ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Muscle wasting, or the loss of muscle tissue, is a common problem for people with cancer, but the precise mechanisms have long eluded doctors and scientists. Now, a new study led by Penn State researchers gives new clues to how muscle wasting happens on a cellular level.

Using a mouse model of ovarian cancer, the researchers found that cancer progression led to fewer skeletal muscle ribosomes -- particles in the cell that make proteins. Because muscle mass is mainly determined by protein synthesis, having less ribosomes likely explains why muscles waste away in cancer.

Gustavo Nader, associate professor of kinesiology and physiology at Penn State, said the findings suggest a mechanism for muscle wasting that could be relevant ...

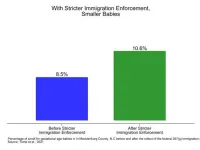

DURHAM, N.C. -- Harsher immigration law enforcement by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement leads to decreased use of prenatal care for immigrant mothers and declines in birth weight, according to new Duke University research.

In the study, published in PLOS ONE, researchers examine the effects of the federal 287(g) immigration program after it was introduced in North Carolina in 2006. Under 287(g) programs, which are still in effect, local law officers are deputized to act as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, with authority to question individuals about immigration status, detain them, and if necessary, begin deportation proceedings.

According to the study findings, the 2006 policy change reduced birth weight ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Hypoxia -- where a tissue is deprived of an adequate supply of oxygen -- is a feature inside solid cancer tumors that renders them highly invasive and resistant to treatment. Study of how cells adapt to this critical stressor, by altering their metabolism to survive in a low-oxygen environment, is important to better understand tumor growth and spread.

Researchers led by Rajeev Samant, Ph.D., professor of pathology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, now report that chronic hypoxia, surprisingly, upregulates RNA polymerase I activity and alters the methylation patterns on ribosomal RNAs. These altered epigenetic marks on the ribosomal RNAs appear to create a pool of specialized ribosomes that can differentially ...