(Press-News.org) Lots of us are feeling pretty anxious about the destruction of the natural world. It turns out, humans aren't the only ones stressing out--by analyzing hormones that accumulate in fur, researchers found that rodents and marsupials living in smaller patches of South America's Atlantic Forest are under more stress than ones living in more intact forests.

"We suspected that organisms in deforested areas would show higher levels of stress than animals in more pristine forests, and we found evidence that that's true," says Noé de la Sancha, a research associate at the Field Museum in Chicago, Associate Professor of Biology at Chicago State University, and co-author of a new paper in Scientific Reports detailing the discovery. "Small mammals, primarily rodents and little marsupials, tend to be more stressed out, or show more evidence that they have higher levels of stress hormones, in smaller forest patches than in larger forest patches."

"A lot of species, all over the world, but especially in the tropics, are understudied," says Sarah Boyle, an Associate Professor of Biology and Chair of the Environmental Studies and Sciences Program at Rhodes College and the study's lead author. "There is not a lot known about many of these animals in terms of even their baseline hormone levels."

The Atlantic Forest is often overshadowed by its neighbor the Amazon, but it's South America's second-largest forest, extending from northeastern Brazil down south along the Brazilian coastline, into northwestern Argentina to eastern Paraguay. It once covered about 463,000 square miles, an area bigger than California, Oregon, Washington, and Nevada put together. Since the arrival of Portuguese colonists 500 years ago, parts of the forest have been destroyed to make way for farmland and urban areas; today, less than one-third of the original forest remains.

The destruction of an animal's habitat can drastically change its life. There's less food and territory to go around, and the animal might find itself in more frequent contact with predators or in increased competition with other animals for resources. These circumstances can add up to long-term stress.

Stress isn't a bad thing in and of itself--in small doses, stress can be life-saving. "A stress response is normally trying to bring your body back into balance," says David Kabelik, an Associate Professor of Biology and Chair of the Neuroscience Program at Rhodes College and one of the paper's authors. "If something perturbs you and it can cause you to be injured or die, the stress response mobilizes energy to deal with that situation and bring things back into a normal state. It allows you to survive." For instance, if an animal encounters a predator, a flood of stress hormones can give them the energy they need to run away, and then those hormone levels go back down to normal. "But then these animals are placed into these small fragments of habitat where they're experiencing elevated stress over prolonged periods, and that can lead to disease and dysregulation of various physiological mechanisms in the body."

For this study, the researchers focused on patches of forest in eastern Paraguay, which has been particularly hard hit in the last century as the region was clear-cut for firewood, cattle farming, and soy. To study the effects of this deforestation, the researchers trapped 106 mammals from areas ranging from 2 to 1,200 hectares--the size of a city block to 4.63 square miles. The critters they analyzed included five species of rodents and two species of marsupials.

The researchers took samples of the animals' fur, since hormones accumulate in hair over periods of many days or weeks, and could present a clearer picture of the animals' typical stress levels than the hormones present in a blood sample. "Hormones change in the blood minute by minute, so that's not really an accurate reflection of whether these animals are under long-term stress or whether they just happened to run away from a predator a minute ago," says Kabelik, "and we were trying to get at something that's more of an indicator of longer term stress. Since glucocorticoid stress hormones get deposited into the fur over time, if you analyze these samples you can look at a longer term measure of their stress."

Back in the lab, the researchers ground the fur into a fine powder and extracted the hormones. They analyzed hormone levels using enzyme immunoassay:"You use antibodies that bind these hormones to figure out how many are there," says Kabelik. "Then you divide that by the amount of fur that was in the sample, and it tells you the amount of hormones present per milligram."

The team found that the animals from smaller patches of forest had higher levels of glucocorticoid stress hormones than animals from larger patches of forest. "Our findings that animals in the small forest patches had higher glucocorticoid levels was not surprising, given the extent to which some of these forested areas have been heavily impacted by forest loss and fragmentation," says Boyle.

"In particular, these findings are highly relevant for countries like Paraguay that currently show an accelerated rate of change in natural landscapes. In Paraguay, we are just beginning to document how the diversity of species that are being lost is distributed," says Pastor Pérez, a biologist at Universidad Nacional de Asunción and another of the paper's authors. "However, this paper shows that we also have a lot to learn about how these species interact in these environments."

The scientists also found that the methods of trapping the animals contributed to the amount of stress hormones present. "It's an important consideration that people have to understand when they're doing these studies, that if they are live trapping the animals, that might be influencing the measured hormone levels," says Kabelik.

The study not only sheds light on how animals respond to deforestation, but it could also lead to a better understanding of the circumstances in which animals can pass diseases to humans. "If you have lots of stressed out mammals, they can harbor viruses and other diseases, and there are more and more people living near these deforested patches that could potentially be in contact with these animals," says de la Sancha. "By destroying natural habitats, we're potentially creating hotspots for zoonotic disease outbreaks."

And, the researchers say, the results of this study go far beyond South America's Atlantic Forest.

"Big picture, this is really important because it could be applicable to forest remnants throughout the world," says de la Sancha. "The tropics hold the highest diversity of organisms on the planet. Therefore, this has potential to impact the largest variety of living organisms on the planet, as more and more deforestation is happening. We're gonna see individuals and populations that tend to show higher levels of stress."

INFORMATION:

New research published today in the journal Scientific Reports based on the largest-to-date analysis of commercial data on egg-laying hen mortality finds that mortality in higher-welfare cage-free housing systems decreases over time as management experience increases and knowledge accrues.

This finding marks a major turning point in the debate over the transition in housing systems for egg-laying hens from battery cages to indoor cage-free systems, which some egg producers have argued would increase hens' mortality even as it allowed birds to stretch their wings.

The study, authored by Dr. Cynthia Schuck-Paim and others, included data from 16 countries, 6,040 commercial flocks, and 176 million hens in a variety of caged and ...

DALLAS, Feb. 4, 2021 -- Stroke and heart attack survivors can reduce multiple causes of death and prevent further cardiovascular events by drinking green tea, according to new research published today in Stroke, a journal of the American Stroke Association, a division of the American Heart Association. The study also found daily coffee consumption helps heart attack survivors by lowering their risk of death after a heart attack and can prevent heart attacks or strokes in healthy individuals.

Previous research has examined the benefits of green tea and coffee on heart health in people without a history of cardiovascular disease or cancer. Researchers in ...

BOSTON - Medical histories of patients collected and stored in electronic health records (EHR) can be rapidly leveraged to predict the probability of death from COVID-19, information that could prove valuable in managing limited therapeutic and preventive resources to combat the devastating virus, researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have found. In a study published in npj Digital Medicine, the team described how artificial intelligence (AI) technology enabled it to identify factors such as age, history of pneumonia, gender, race and comorbidities like diabetes and cancer as predictors of poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients.

"By combining computational methods and clinical expertise, we developed a set of models to forecast ...

The open ocean is a harsh place for newborn fishes. From the minute larvae hatch from their eggs, their survival depends upon finding food and navigating ocean currents to their adult habitats--all while avoiding predators. This harrowing journey from egg to home has long been a mystery, until now.

An international team including scientists from the Arizona State University Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science (GDCS), NOAA's Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, and the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa have discovered a diverse array of young marine animals finding refuge within so-called 'surface slicks' in Hawai'i. Surface slicks create a superhighway of nursery habitat for more than 100 species of commercially and ecologically ...

To survive the open ocean, tiny fish larvae, freshly hatched from eggs, must find food, avoid predators, and navigate ocean currents to their adult habitats. But what the larvae of most marine species experience during these great ocean odysseys has long been a mystery, until now.

A team of scientists from NOAA's Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, the University of Hawai'i (UH) at Mānoa, Arizona State University and elsewhere have discovered that a diverse array of marine animals find refuge in so-called 'surface slicks' in Hawai'i. These ocean features ...

The Institute for Scientific Information on Coffee (ISIC) published a new report today, titled 'Coffee and sleep in everyday lives', authored by Professor Renata Riha, from the Department of Sleep Medicine at the University of Edinburgh. It reviews the latest research into coffee's effect on sleep and suggests that while drinking coffee early in the day can help support alertness and concentration levels1, especially when sleep patterns are disturbed; decreasing intake six hours before bedtime may help reduce its impact on sleep2.

Coffee is largely consumed daily for the pleasure of its taste3, as well as its beneficial effect on wakefulness and concentration (due to its caffeine content)4. ...

A new study further highlighting a potential physiological cause of clinical depression could guide future treatment options for this serious mental health disorder. Published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, researchers show differences between the cellular composition of the brain in depressed adults who died by suicide and non-psychiatric individuals who died suddenly by other means.

"We found a reduced number of astrocytes, highlighted by staining the protein vimentin, in many regions of the brain in depressed adults," reports Naguib Mechawar, a Professor at the Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Canada, and senior author of this article. ...

Researchers from University of Notre Dame, York University (Canada), and University of New England (Australia) published a new paper in the Journal of Marketing that identifies a novel reason why people under-save and demonstrates a simple, short, and inexpensive intervention that increases intentions to save and actual savings.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled "Popping the Positive Illusion of Financial Responsibility Can Increase Personal Savings: Applications in Emerging and Western Markets" and is authored by Emily Garbinsky, Nicole Mead, and Daniel Gregg.

People around the world are not saving enough money. Since increasing ...

WASHINGTON--The start of California's annual rainy season has been pushed back from November to December, prolonging the state's increasingly destructive wildfire season by nearly a month, according to new research. The study cannot confirm the shift is connected to climate change, but the results are consistent with climate models that predict drier autumns for California in a warming climate, according to the authors.

Wildfires can occur at any time in California, but fires typically burn from May through October, when the state is in its dry season. The start of the rainy season, historically in November, ends wildfire season as plants become too moist to burn.

California's rainy season has been starting progressively later in recent decades and climate ...

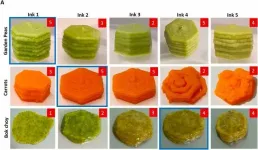

Researchers from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore), Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH) have developed a new way to create "food inks" from fresh and frozen vegetables, that preserves their nutrition and flavour better than existing methods.

Food inks are usually made from pureed foods in liquid or semi-solid form, then 3D-printed by extrusion from a nozzle, and assembled layer by layer.

Pureed foods are usually served to patients suffering from swallowing difficulties known as dysphagia. To present the ...