Electronic health records can be valuable predictor of those likeliest to die from COVID

Factors such as age, history of pneumonia, and comorbidities like diabetes and cancer emerged as predictors of poor outcomes.

2021-02-04

(Press-News.org) BOSTON - Medical histories of patients collected and stored in electronic health records (EHR) can be rapidly leveraged to predict the probability of death from COVID-19, information that could prove valuable in managing limited therapeutic and preventive resources to combat the devastating virus, researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have found. In a study published in npj Digital Medicine, the team described how artificial intelligence (AI) technology enabled it to identify factors such as age, history of pneumonia, gender, race and comorbidities like diabetes and cancer as predictors of poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients.

"By combining computational methods and clinical expertise, we developed a set of models to forecast the most severe COVID-19 outcomes based on past medical records, and to help understand the differences in risk factors across age groups," says co-lead author Hossein Estiri, PhD, an investigator in the Laboratory of Computer Science at MGH and an assistant professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School (HMS). "Many prior studies have isolated small subsets of EHR data from after the infection, but ours is the first and largest to use entire historical medical records to try to untangle the role of age as the most important risk factor for COVID adverse outcomes."

The analytics/medical team drew on the COVID-19 "datamart" that had been created by hospital system Mass General Brigham for research, a repository of frequently refreshed longitudinal data on COVID-19 patients from across the system. Using electronic medical records from more than 16,000 such patients, the MGH team applied a computational algorithm -- with a human expert in the loop -- to identify 46 clinical conditions representing potential risk factors for death after a COVID-19 infection. "Despite relying on only previously documented demographics and comorbidities, our models demonstrated performance comparable to more complex prognostic models requiring an assortment of symptoms, laboratory values and images gathered at the time of diagnosis or during the course of the illness," notes Zachary Strasser, MD, co-lead author and postdoctoral fellow at MGH.

The MGH study found age to be the most important predictor of mortality in COVID-19 patients. A history of pneumonia was also identified by the study as a significant risk factor, as were histories of diabetes with complications, and cancer (particularly breast and prostate) among COVID-19 patients between the ages of 45 and 65. In patients between 65 and 85, diseases affecting the pulmonary system -- including interstitial lung disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung cancer, and a history of smoking - were strong predictors of poor outcomes. Comorbidities registering the highest odds ratios for death irrespective of age were chronic kidney disease, heart failure, abdominal aortic aneurysm, hypertension and aortic valve disease.

As for gender, the study found females to be at lower risk of death from COVID-19. Even after adjusting for age and chronic diseases, the researchers learned that women benefited from an unknown form of underlying protection against the worst outcome of the viral infection. In their overall model, researchers did not find evidence that a certain race or ethnicity altered the odds of mortality after contracting COVID-19. They did find in the oldest cohort of patients, however, that being African American was associated with a higher chance of mortality.

The sheer volume of EHR information and its marriage to predictive analytics becomes particularly important during a pandemic when access to large-scale, clinical trial grade data is not practical, emphasizes Shawn Murphy, MD, PhD, senior author and chief research informatics officer at Mass General Brigham. "The ability to quickly utilize data that has already been collected across the country to compute individual-level risk scores," he says, "is crucial for effectively allocating and distributing resources, including prioritizing vaccination among the general population."

INFORMATION:

The researchers are from the MGH Laboratory of Computer Science; the Department of Biomedical Informatics at HMS; and the MGH Department of Neurology.

The study was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute and the National Library of Medicine.

About the Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of more than $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. In August 2020, Mass General was named #6 in the U.S. News & World Report list of "America's Best Hospitals."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-04

The open ocean is a harsh place for newborn fishes. From the minute larvae hatch from their eggs, their survival depends upon finding food and navigating ocean currents to their adult habitats--all while avoiding predators. This harrowing journey from egg to home has long been a mystery, until now.

An international team including scientists from the Arizona State University Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science (GDCS), NOAA's Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, and the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa have discovered a diverse array of young marine animals finding refuge within so-called 'surface slicks' in Hawai'i. Surface slicks create a superhighway of nursery habitat for more than 100 species of commercially and ecologically ...

2021-02-04

To survive the open ocean, tiny fish larvae, freshly hatched from eggs, must find food, avoid predators, and navigate ocean currents to their adult habitats. But what the larvae of most marine species experience during these great ocean odysseys has long been a mystery, until now.

A team of scientists from NOAA's Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, the University of Hawai'i (UH) at Mānoa, Arizona State University and elsewhere have discovered that a diverse array of marine animals find refuge in so-called 'surface slicks' in Hawai'i. These ocean features ...

2021-02-04

The Institute for Scientific Information on Coffee (ISIC) published a new report today, titled 'Coffee and sleep in everyday lives', authored by Professor Renata Riha, from the Department of Sleep Medicine at the University of Edinburgh. It reviews the latest research into coffee's effect on sleep and suggests that while drinking coffee early in the day can help support alertness and concentration levels1, especially when sleep patterns are disturbed; decreasing intake six hours before bedtime may help reduce its impact on sleep2.

Coffee is largely consumed daily for the pleasure of its taste3, as well as its beneficial effect on wakefulness and concentration (due to its caffeine content)4. ...

2021-02-04

A new study further highlighting a potential physiological cause of clinical depression could guide future treatment options for this serious mental health disorder. Published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, researchers show differences between the cellular composition of the brain in depressed adults who died by suicide and non-psychiatric individuals who died suddenly by other means.

"We found a reduced number of astrocytes, highlighted by staining the protein vimentin, in many regions of the brain in depressed adults," reports Naguib Mechawar, a Professor at the Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Canada, and senior author of this article. ...

2021-02-04

Researchers from University of Notre Dame, York University (Canada), and University of New England (Australia) published a new paper in the Journal of Marketing that identifies a novel reason why people under-save and demonstrates a simple, short, and inexpensive intervention that increases intentions to save and actual savings.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled "Popping the Positive Illusion of Financial Responsibility Can Increase Personal Savings: Applications in Emerging and Western Markets" and is authored by Emily Garbinsky, Nicole Mead, and Daniel Gregg.

People around the world are not saving enough money. Since increasing ...

2021-02-04

WASHINGTON--The start of California's annual rainy season has been pushed back from November to December, prolonging the state's increasingly destructive wildfire season by nearly a month, according to new research. The study cannot confirm the shift is connected to climate change, but the results are consistent with climate models that predict drier autumns for California in a warming climate, according to the authors.

Wildfires can occur at any time in California, but fires typically burn from May through October, when the state is in its dry season. The start of the rainy season, historically in November, ends wildfire season as plants become too moist to burn.

California's rainy season has been starting progressively later in recent decades and climate ...

2021-02-04

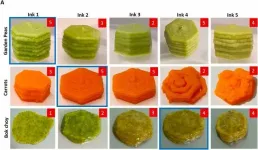

Researchers from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore), Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH) have developed a new way to create "food inks" from fresh and frozen vegetables, that preserves their nutrition and flavour better than existing methods.

Food inks are usually made from pureed foods in liquid or semi-solid form, then 3D-printed by extrusion from a nozzle, and assembled layer by layer.

Pureed foods are usually served to patients suffering from swallowing difficulties known as dysphagia. To present the ...

2021-02-04

Politicians around the world must be held to account for mishandling the covid-19 pandemic, argues a senior editor at The BMJ today.

Executive editor, Dr Kamran Abbasi, argues that at the very least, covid-19 might be classified as 'social murder' that requires redress.

Today 'social murder' may describe a lack of political attention to the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age that exacerbate the pandemic.

When politicians and experts say that they are willing to allow tens of thousands of premature deaths, for the sake of population immunity or in the hope of propping up the economy, is that not premeditated ...

2021-02-03

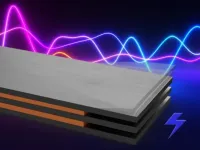

Piezoelectric materials hold great promise as sensors and as energy harvesters but are normally much less effective at high temperatures, limiting their use in environments such as engines or space exploration. However, a new piezoelectric device developed by a team of researchers from Penn State and QorTek remains highly effective at elevated temperatures.

Clive Randall, director of Penn State's Materials Research Institute (MRI), developed the material and device in partnership with researchers from QorTek, a State College, Pennsylvania-based company specializing in smart material devices and high-density power electronics.

"NASA's need ...

2021-02-03

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Muscle wasting, or the loss of muscle tissue, is a common problem for people with cancer, but the precise mechanisms have long eluded doctors and scientists. Now, a new study led by Penn State researchers gives new clues to how muscle wasting happens on a cellular level.

Using a mouse model of ovarian cancer, the researchers found that cancer progression led to fewer skeletal muscle ribosomes -- particles in the cell that make proteins. Because muscle mass is mainly determined by protein synthesis, having less ribosomes likely explains why muscles waste away in cancer.

Gustavo Nader, associate professor of kinesiology and physiology at Penn State, said the findings suggest a mechanism for muscle wasting that could be relevant ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Electronic health records can be valuable predictor of those likeliest to die from COVID

Factors such as age, history of pneumonia, and comorbidities like diabetes and cancer emerged as predictors of poor outcomes.