Human-elephant conflict in Kenya heightens with increase in crop-raiding

A study led by the University of Kent's Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology has found that elephants living around the Masai Mara National Reserve, Kenya, are crop-raiding closer to the protected area, more frequently and throughout the year

2021-02-04

(Press-News.org) A new study led by the University of Kent's Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE) has found that elephants living around the world-famous Masai Mara National Reserve, Kenya, are crop-raiding closer to the protected area, more frequently and throughout the year but are causing less damage when doing so.

Findings show that the direct economic impact of this crop-raiding in the Trans Mara region has dropped, yet farmers have to spend more time protecting their fields, further reducing support for conservation in communities who currently receive few benefits from living with wildlife.

The research published by Biological Conservation demonstrates the effects that climate change, agricultural expansion and increased cattle grazing within the reserve have had on elephant crop-raiding trends in the region.

The team of conservationists, led by Professor Bob Smith and DICE alumna Dr Lydia Tiller (Research and Science Manager, Save the Elephants), investigated the seasonal, temporal and spatial trends of elephant crop-raiding in the Trans Mara, Kenya during 2014-2015, comparing results to a previous DICE study from 1999 to 2000.

The number of crop-raiding incidents increased by 49% over the 15 years, but crop damage per incident dropped by 83%. This could be because farmers are better prepared to frighten off elephants. It could also be because landcover change makes it harder for elephants to hide in forest patches, and this spread of farmland and loss of forest to illegal charcoal clearing means that more of the crop-raiding incidents are taking place closer to the protected area.

Professor Smith said: 'Landcover change has had a major impact on where human-elephant conflict takes place. Better land-use planning and support for farmers would help reduce crop-raiding as well as people's tolerance of elephants.'

Lydia Tiller said: 'The change in crop-raiding trends going from being highly seasonal during 1999-2000 when maize crops are ripe, to year-round during 2014-2015, is yet another demonstration of how climate change is affecting nature. With less natural vegetation available for elephants to eat in the Masai Mara, this is not surprising. Restoring elephants' feeding habitat in the park is vital to reducing human-elephant conflict in the area.'

INFORMATION:

Their research paper 'Changing seasonal, temporal and spatial crop-raiding trends over 15 years in a human-elephant conflict hotspot' is published by Biological Conservation. DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108941

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-04

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- All things being equal, large, long-lived animals should have the highest risk of cancer.

The calculation is simple: Tumors grow when genetic mutations cause individual cells to reproduce too quickly. A long life creates more opportunities for those cancerous mutations to arise. So, too, does a massive body: Big creatures -- which have many more cells -- should develop tumors more frequently.

Why, then, does cancer rarely afflict elephants, with their long lifespans and gargantuan bodies? They are some of the world's largest land animals.

A new study delves into this ...

2021-02-04

Laparoscopic surgery, a less invasive alternative to conventional open surgery, involves inserting thin tubes with a tiny camera and surgical instruments into the abdomen. To visualize specific surgical targets, ultrasound imaging is used in conjunction with the surgery. However, ultrasound images are viewed on a separate screen, requiring the surgeon to mentally combine the camera and ultrasound data.

Modern augmented reality (AR)-based methods have overcome this issue by embedding ultrasound images into the video taken by the laparoscopic camera. These AR methods precisely map the ultrasound data coordinates to the coordinates of the ...

2021-02-04

Over the past 30 years, the use of soil fumigants and nematicides used to protect cole crops, such as broccoli and Brussel sprouts, against cyst nematode pathogens in coastal California fields has decreased dramatically. A survey of field samples in 2016 indicated the nematode population has also decreased, suggesting the existence of a natural cyst nematode controlling process in these fields.

Thanks to California's pesticide-use reporting program, nematologists have been able to follow the amounts of fumigants and nematicides used to control cyst nematodes over the past three decades.

"Application of these pesticides steadily declined until they were completely eliminated in ...

2021-02-04

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to devastate communities worldwide, Black Americans who face racial discrimination in hospitals and doctor's offices weather additional stresses that can exacerbate threats from COVID-19. A new University of Georgia study examines the interplay between the perceptions of coronavirus threat and psychological distress among Black Americans.

The additional stresses arise from the prevalent belief among Black Americans worried that they might not recover from how hospitals treat them if they become infected with the coronavirus.

"While the notion has been floated among commentators, this is the first study that uses nationally representative data to assess whether this threat, or feeling, ...

2021-02-04

BOSTON - Tiny particles of air pollution -- called fine particulate matter -- can have a range of effects on health, and exposure to high levels is a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease. New research led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) reveals that fine particulate matter has a detrimental impact on cardiovascular health by activating the production of inflammatory cells in the bone marrow, ultimately leading to inflammation of the arteries. The findings are published in the END ...

2021-02-04

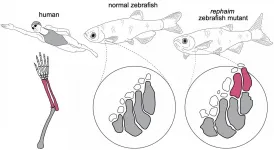

By tweaking a single gene, Harvard scientists engineered zebrafish that show the beginning formation of limb-like appendages. The researchers stumbled upon this mutation, which may shed light on the sea-to-land transition of vertebrates, while screening for various gene mutants and their impact on fish development. Their discovery, outlined February 4th in the journal Cell, marks a fundamental step in our understanding of fin-to-limb evolution and how surprisingly simple genetic changes can create great leaps in the development of complex structures.

"It was a little bit unbelievable that just one mutation was able to create completely new bones and joints," says M. Brent Hawkins (@Homeobox), first author of ...

2021-02-04

Fin-to-limb transition is an icon of key evolutionary transformations. Many studies focus on understanding the evolution of the simple fin into a complicated limb skeleton by examining the fossil record. In a paper published February 4 in Cell, researchers at Harvard and Boston Children's Hospital examined what's occurring at the genetic level to drive different patterns in the fin skeleton versus the limb skeleton.

Researchers, led by M. Brent Hawkins, a recent doctoral recipient in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, performed forward genetic screens in zebrafish looking for mutations that affect the fin skeleton. Unlike tetrapod limbs, which have complex skeletons with many bones that articulate ...

2021-02-04

Although scientists knew that some bats could reach heights of over 1,600 meters (or approximately one mile) above the ground during flight, they didn't understand how they managed to do it without the benefit of thermals that aren't typically available to them during their nighttime forays. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 4th have uncovered the bats' secret to high-flying.

It turns out that the European free-tailed bats they studied--powerful fliers that the researchers documented sometimes reaching speeds of up to 135 kilometers (84 miles) per hour in self-powered flight--do depend on orographic uplift that ...

2021-02-04

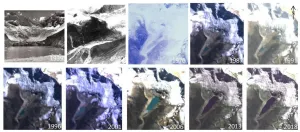

As the planet warms, glaciers are retreating and causing changes in the world's mountain water systems. For the first time, scientists at the University of Oxford and the University of Washington have directly linked human-induced climate change to the risk of flooding from a glacial lake known as one of the world's greatest flood risks.

The study examined the case of Lake Palcacocha in the Peruvian Andes, which could cause flooding with devastating consequences for 120,000 residents in the city of Huaraz. The paper, published Feb. 4 in Nature Geoscience, provides new evidence for an ongoing legal case that hinges on the link between greenhouse gas emissions and particular climate change impacts.

"The scientific challenge was to provide the clearest and cleanest assessment ...

2021-02-04

CHICAGO - A new study by Northwestern University researchers finds involvement with firearms by high-risk youth is associated with firearm violence during adulthood.

"Association of Firearm Access, Use, and Victimization During Adolescence with Firearm Perpetration During Adulthood in a 16-year Longitudinal Study of Youth Involved in the Juvenile Justice System" will publish in JAMA Network Open at 10 a.m. CST, Thursday, Feb. 4. Access the full study online.

The longitudinal study of juvenile justice youth is the first to analyze firearm victimization and access during adolescence and its association with firearm violence in adulthood.

The study is based ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Human-elephant conflict in Kenya heightens with increase in crop-raiding

A study led by the University of Kent's Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology has found that elephants living around the Masai Mara National Reserve, Kenya, are crop-raiding closer to the protected area, more frequently and throughout the year