Critical flaw found in lab models of the human blood-brain barrier

2021-02-05

(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY (Feb. 5, 2020)--Cells used to study the human blood brain barrier in the lab aren't what they seem, throwing nearly a decade's worth of research into question, a new study from scientists at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and Weill Cornell Medicine suggests.

The team also discovered a possible way to correct the error, raising hopes of creating a more accurate model of the human blood-brain barrier for studying certain neurological diseases and developing drugs that can cross it.

The study was published online Feb. 4 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

"The blood-brain barrier is difficult to study in humans and there are many differences between the human and animal blood-brain barrier. So it's very helpful to have a model of the human blood-brain barrier in a dish," says co-study leader Dritan Agalliu, PhD, associate professor of pathology and cell biology (in neurology) at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

The in vitro human blood-brain barrier model, developed in 2012, is made by coaxing differentiated adult cells, such as skin cells, into stem cells that behave like embryonic stem cells. These induced pluripotent stem cells can then be transformed into mature cells of almost any type--including a type of endothelial cell that lines the blood vessels of the brain and spinal cord and forms a unique barrier that normally restricts the entry of potentially dangerous substances, antibodies, and immune cells from the bloodstream into the brain.

Agalliu previously noticed that these induced human "brain microvascular endothelial cells," produced using the published approach in 2012, did not behave like normal endothelial cells in the human brain. "This raised my suspicion that the protocol for making the barrier's endothelial cells may have generated cells of the wrong identity," says Agalliu.

"At the same time the Weill Cornell Medicine team had similar suspicions, so we teamed up to reproduce the protocol and perform bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing of these cells."

Their analysis revealed that the supposed human brain endothelial cells were missing several key proteins found in natural endothelial cells and had more in common with a completely different type of cell (epithelial) that is normally not found in the brain.

The team also identified three genes that, when activated within induced pluripotent cells, lead to the creation of cells that behave more like bona fide endothelial cells. More work is still needed, Agalliu says, to create endothelial cells that produce a reliable model of the human blood-brain barrier. His team is working to address this problem.

"The misidentification of human brain endothelial cells may be an issue for other types of cells made from induced pluripotent cells such as astrocytes or pericytes that form the neurovascular unit," Agalliu says. The protocols to generate these cells were created before the advent of single-cell technologies that are better at uncovering a cell's identity. "Cell misidentification remains a major problem that needs to be addressed in the scientific community in order to develop cells that mirror those found in the human brain. This will allow us to use these cells to study the role of genetic risk factors for neurological disorders and develop drug therapies that target the correct cells that contribute to the blood-brain barrier."

INFORMATION:

More Information

The study is titled, "Pluripotent stem cell-derived epithelium misidentified as brain microvascular endothelium requires ETS factors to acquire vascular fate."

The other contributors are: Tyler M. Lu (Weill Cornell Medicine), Sean Houghton (Weill Cornell Medicine), Tarig Magdeldin (Weill Cornell Medicine), José Gabriel Barcia Durán (Weill Cornell Medicine), Andrew P. Minotti (Weill Cornell Medicine), Amanda Snead (Columbia), Andrew Sproul (Columbia), Duc-Huy T. Nguyen (Weill Cornell Medicine), Jenny Xiangh (Weill Cornell Medicine), Howard A. Fine (Weill Cornell Medicine), Zev Rosenwaks (Weill Cornell Medicine), Lorenz Studer (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and Weill Cornell), Shahin Rafii (Weill Cornell Medicine), David Redmond (Weill Cornell Medicine), and Raphaël Lis (Weill Cornell Medicine).

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health

(grants R01MH112849, R01NS107344, RF1AG054023, DP1CA228040, and RF1AG054023), the Leducq Foundation, John Castle (Newport Equity LLC), the PANDAS Network, the Thompson Foundation, the Henry and Marylin Taub Foundation, NYSTEM, the Ansary Stem Cell Institute, and the Starr Foundation TRI-Institution Stem Cell Initiative.

The authors report no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Columbia University Irving Medical Center provides international leadership in basic, preclinical, and clinical research; medical and health sciences education; and patient care. The medical center trains future leaders and includes the dedicated work of many physicians, scientists, public health professionals, dentists, and nurses at the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing, the biomedical departments of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and allied research centers and institutions. Columbia University Irving Medical Center is home to the largest medical research enterprise in New York City and State and one of the largest faculty medical practices in the Northeast. For more information, visit cuimc.columbia.edu or columbiadoctors.org.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-05

Washington, DC, February 5, 2021 - A study in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (JAACAP), published by Elsevier, reports that in a diverse, cross-national sample of youth, physical discipline and cognitive deprivation had distinct associations with specific domains of developmental delay. The findings are based on the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, which is an ongoing, international household survey initiative coordinated and assisted by the United Nations agency, UNICEF.

"Physical discipline and cognitive deprivation are well-established risks to child development. However, it is rare that these experiences are examined in relation to each other," said lead author ...

2021-02-05

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa.-- When actor Tom Hanks announced his COVID-19 diagnosis on March 11, 2020, many Americans were still learning about the virus and its severity. According to new research, Hanks' announcement may have affected how some people understood the virus and their behavior toward its prevention.

The day after Hanks posted the news on social media, Jessica Gall Myrick, an associate professor in the Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications at Penn State, and Jessica Fitts Willoughby, associate professor at Washington State University, surveyed 682 people about their attitudes and behaviors toward COVID-19.

Just under 90% of the people surveyed had heard about Hanks' social ...

2021-02-05

Virtual reality isn't just for gaming. Researchers can use virtual reality, or VR, to assess participants' attention, memory and problem-solving abilities in real world settings. By using VR technology to examine how folks complete daily tasks, like making a grocery list, researchers can better help clinical populations that struggle with executive functioning to manage their everyday lives.

Lead author Zhengsi Chang is a PhD student that works in the lab of Daniel Krawczyk, PhD, deputy director of the Center for BrainHealth®. Along with Brandon Pires, a researcher at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, the team investigated whether VR can be used to effectively test ...

2021-02-05

New research affirms a unique peptide found in an Australian plant can destroy the No. 1 killer of citrus trees worldwide and help prevent infection.

Huanglongbing, HLB, or citrus greening has multiple names, but one ultimate result: bitter and worthless citrus fruits. It has wiped out citrus orchards across the globe, causing billions in annual production losses.

All commercially important citrus varieties are susceptible to it, and there is no effective tool to treat HLB-positive trees, or to prevent new infections.

However, new UC Riverside research shows that a naturally occurring peptide found in HLB-tolerant citrus relatives, such as Australian finger lime, can not only kill the bacteria that causes the disease, it can also activate the plant's ...

2021-02-05

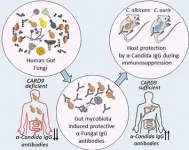

Common fungi, often present in the gut, teach the immune system how to respond to their more dangerous relatives, according to new research from scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine. Breakdowns in this process can leave people susceptible to deadly fungal infections.

The study, published Feb. 5 in Cell, reveals a new twist in the complex relationship between humans and their associated microbes, and points the way toward novel therapies that could help combat a rising tide of drug-resistant pathogens.

The new discovery stemmed from work on inflammatory bowel disease, which often causes patients to carry larger than normal populations of fungi in their guts. ...

2021-02-05

To arrive at Nunavut, turn left at the Dakotas and head north. You can't miss it--the vast tundra territory covers almost a million square miles of northern Canada. Relatively few people call this lake-scattered landscape home, but the region plays a crucial role in understanding global climate change. New research from Soren Brothers, assistant professor in the Department of Watershed Sciences and Ecology Center, details how lakes in Nunavut could have a big impact on carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, and it's not all bad news--at least for now. Brothers examined 23 years of data from lakes near Rankin Inlet. He noted a peculiarity--as the lakes warmed, their carbon dioxide concentrations fell. ...

2021-02-05

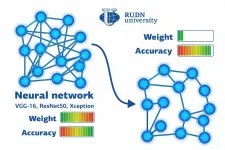

A team of mathematicians from RUDN University found a way to reduce the size of a trained neural network six times without spending additional resources on re-training it. The approach is based on finding a correlation between the weights of neural connections in the initial system and its simplified version. The results of the work were published in the Optical Memory and Neural Networks journal.

The structures of artificial neural networks and neurons in a living organism are based on the same principles. Nodes in a network are interconnected; some of them receive a signal, and some transmit it by activating or suppressing the next element in the chain. The processing of any signal (for ...

2021-02-05

The discovery of an "Achilles heel" in a type of gut bacteria that causes intestinal inflammation in patients with Crohn's disease may lead to more targeted therapies for the difficult to treat disease, according to Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian investigators.

In a study published Feb. 3 in Cell Host and Microbe, the investigators showed that patients with Crohn's disease have an overabundance of a type of gut bacteria called adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), which promotes inflammation in the intestine. Their experiments revealed ...

2021-02-05

Progressive vision loss, and eventually blindness, are the hallmarks of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL) or CLN3-Batten disease. New research shows how the mutation associated with the disease could potentially lead to degeneration of light sensing photoreceptor cells in the retina, and subsequent vision loss.

"The prominence and early onset of retinal degeneration in JNCL makes it likely that cellular processes that are compromised in JNCL are critical for health and function of the retina," said Ruchira Signh, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Ophthalmology and Center for Visual Science and lead author of the study which appears in the journal Communications Biology. "It is important to understand how vision loss is triggered in this disease, ...

2021-02-05

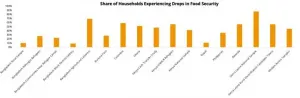

Washington, D.C.. -- The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic caused a sharp decline in living standards and rising food insecurity in developing countries across the globe, according to a new study by an international team of economists.

The study, published Feb. 5 in the journal Science Advances, provides an in-depth view of the health crisis's initial socioeconomic effects in low- and middle-income countries, using detailed micro data collected from tens of thousands of households across nine countries. The phone surveys were conducted from April through July 2020 of nationally and sub-nationally representative samples in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, Nepal, Philippines, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone. Across the board, study ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Critical flaw found in lab models of the human blood-brain barrier