(Press-News.org) Older adults who are classified as having "prediabetes" due to moderately elevated measures of blood sugar usually don't go on to develop full-blown diabetes, according to a study led by researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Doctors still consider prediabetes a useful indicator of future diabetes risk in young and middle-aged adults. However, the study, which followed nearly 3,500 older adults, of median age 76, for about six and a half years, suggests that prediabetes is not a useful marker of diabetes risk in people of more advanced age.

The results were published February 8 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

"Our results suggest that for older adults with blood sugar levels in the prediabetes range, few will actually develop diabetes," says study senior author Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Bloomberg School. "The category of prediabetes doesn't seem to be helping us identify high-risk people. Doctors instead should focus on healthy lifestyle changes and important disease risk factors such as smoking, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol."

Type 2 diabetes leads to a chronically excess blood level of glucose, which stresses organs including the kidneys, weakens the immune system, and damages blood vessels, promoting heart disease and stroke among other conditions. The prevalence of diagnosed type 2 diabetes in the United States has gone from less than one percent in the 1950s to more than 7 percent today--and researchers believe that the actual figure now, including undiagnosed diabetes, is over 12 percent. This sharp increase is due to the aging U.S. population and increased rates of overweight and obesity.

Doctors have used the concept of prediabetes--involving blood glucose levels that are higher than normal but not yet in the diabetic range--as an indicator of elevated diabetes risk in younger and middle-aged people. However, the utility of the concept in older adults--especially those 70 and older--has been less clear.

"It's very common for older adults to have at least mildly elevated blood glucose levels, but how likely they are to progress to diabetes has been an unresolved question," Selvin says.

To get a better picture of how older adults with prediabetes fare, Selvin and colleagues turned to the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. This large epidemiological cohort project, funded by the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and including both Black and white participants, has been running at four U.S. medical centers, including Johns Hopkins, since 1987. For their prediabetes analysis, the researchers selected 3,412 ARIC study participants who had attended a follow-up visit during 2011-13--a time when the participants were between 71 and 90 years old--and did not have any history of diabetes. The researchers then looked at how measures of the participants' blood glucose levels had changed at the next follow-up visit during 2016-17.

As expected, the researchers found that "prediabetes," defined according to two different blood-test measures, was very common among the participants at the 2011-13 visit. Those with prediabetes, defined by moderately high blood levels of glucose following overnight fasting (the impaired fasting glucose test, or IFG), represented 59 percent of the initial sample, and those with prediabetes defined with a different blood test for glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), represented 44 percent of the initial sample.

However, the results showed that only small numbers of the participants who had prediabetes in 2011-13 had developed diabetes by the time of the 2016-17 visit--8 percent of the IFG-defined prediabetics, and 9 percent of the HbA1c-defined prediabetics.

By contrast, 44 percent of the IFG group and 13 percent of the HbA1c group had improved enough by the 2016-17 visit that their test results were back in the normal range. Moreover, 16 and 19 percent of these two groups had died of other causes by the 2016-17 visit.

The results show that older adults with prediabetes, over intervals like the one in the study, are more likely to have lower blood sugar levels--or to die for other reasons--than to progress to diabetes.

"It appears that in older adults, 'prediabetes' is just not a robust diagnosis," Selvin says.

"Our findings support a focus on lifestyle improvements, including exercise and diet when feasible and safe, for older adults with prediabetes," says Mary Rooney, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Bloomberg School and the paper's first author. "This approach has broad benefits for patients."

Selvin and her colleagues recommend that for older adults, physicians should focus their screening efforts on risk factors, such as hypertension, that are more useful in predicting illness and mortality in this population.

INFORMATION:

"Risk of Progression to Diabetes Among Older Adults with Prediabetes" was authored by Mary Rooney, Andreea Rawlings, James Pankow, Justin Echouffo Tcheugui, Josef Coresh, Richey Sharrett, and Elizabeth Selvin.

Funding was provided by the NHLBI (T32HL007024, K24HL152440) and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK089174).

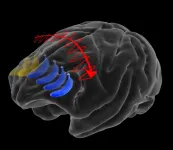

Ask anyone from an NFL quarterback scanning the field for open receivers, to an air traffic controller monitoring the positions of planes, to a mom watching her kids run around at the park: We depend on our brain to hold what we see in mind, even as we shift our gaze around and even temporarily look away. This capability of "visual working memory" feels effortless, but a new MIT study shows that the brain works hard to keep up. Whenever a key object shifts across our field of view--either because it moved or our eyes did--the brain immediately transfers a memory of it by re-encoding it among neurons in the opposite brain hemisphere.

The finding, published in Neuron by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, explains via experiments in animals how we can keep ...

The snapping claws of male amphipods--tiny, shrimplike crustaceans--are among the fastest and most energetic of any life on Earth. Researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 8 find that the crustaceans can repeatedly close their claws in less than 0.01% of a second, generating high-energy water jets and audible pops. The snapping claws are so fast, they almost defy the laws of physics.

"What's really amazing about these amphipods is that they're sitting right on the boundary of what we think is possible in terms of how small something can be and how fast it can move without self-destructing," says senior author Sheila Patek, a Professor of Biology at Duke University. "If they accelerated any faster, their bodies would break."

While amphipods are ...

What The Study Did: The National Health Service in Italy provides universal coverage to citizens but because no approved drug was available for COVID-19, patients received potentially effective drugs, participated in clinical trials, accessed compassionate drug use programs or self-medicated. This study evaluated changes in drug demand during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy compared with the period before the outbreak.

Authors: Adriana Ammassari, M.D., of the Italian Medicines Agency in Rome, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37060)

Editor's ...

Philadelphia, February 8, 2021--Adding to a growing body of research affirming the benefits of fetal surgery for spina bifida, new findings show prenatal repair of the spinal column confers physical gains that extend into childhood. The researchers found that children who had undergone fetal surgery for myelomeningocele, the most severe form of spina bifida, were more likely than those who received postnatal repair to walk independently, go up and down stairs, and perform self-care tasks like using a fork, washing hands and brushing teeth. They also had stronger leg muscles and walked faster than children who had their spina bifida surgery ...

What The Study Did: This observational study compared different measures of prediabetes and the risk of progression to diabetes among adults age 71 to 90.

Authors: Mary R. Rooney, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8774)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and ...

What The Study Did: Researchers assessed what percentage of the Virginia population had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 after the first wave of COVID-19 infections in the U.S.

Authors: Eric R. Houpt, M.D., of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35234)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for ...

If temperature varies strongly from day to day, the economy grows less. Through these seemingly small variations climate change may have strong effects on economic growth. This shows data analyzed by researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), Columbia University and the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC). In a new study in Nature Climate Change, they juxtapose observed daily temperature changes with economic data from more than 1,500 regions worldwide over 40 years - with startling results.

"We ...

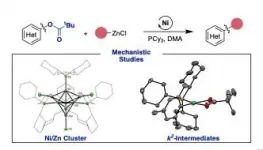

Negishi cross-coupling reactions have been widely used to form C-C bonds since the 1970s and are often perceived as the result of two metals (i.e zinc and palladium/nickel) working in synergy. But like all relationships, there is more under the surface than what we first expected. PhD student Craig Day and Dr. Rosie Somerville from the Martin group at ICIQ have delved into the Negishi cross-coupling of aryl esters using nickel catalysis to understand how this reaction works at the molecular level and how to improve it. The results have been published in Nature Catalysis.

Compared to palladium, nickel has the advantage of being readily available transition metal, ...

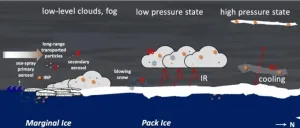

It's clear that rising greenhouse gas emissions are the main driver of global warming. But on a regional level, several other factors are at play. That's especially true in the Arctic - a massive oceanic region around the North Pole which is warming two to three times faster than the rest of the planet. One consequence of the melting of the Arctic ice cap is a reduction in albedo, which is the capacity of surfaces to reflect a certain amount of solar radiation. Earth's bright surfaces like glaciers, snow and clouds have a high reflectivity. As snow and ice decrease, albedo decreases and more radiation is absorbed by the Earth, leading to a rise in ...

What The Study Did: Researchers investigated the association between the use of proton pump inhibitors among children and adolescents in Sweden and the risk of asthma.

Authors: Yun-Han Wang, M.Sc., B.Pharm., of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5710)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict ...