(Press-News.org) Researchers have found a way to use light and a single electron to communicate with a cloud of quantum bits and sense their behaviour, making it possible to detect a single quantum bit in a dense cloud.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, were able to inject a 'needle' of highly fragile quantum information in a 'haystack' of 100,000 nuclei. Using lasers to control an electron, the researchers could then use that electron to control the behaviour of the haystack, making it easier to find the needle. They were able to detect the 'needle' with a precision of 1.9 parts per million: high enough to detect a single quantum bit in this large ensemble.

The technique makes it possible to send highly fragile quantum information optically to a nuclear system for storage, and to verify its imprint with minimal disturbance, an important step in the development of a quantum internet based on quantum light sources. The results are reported in the journal Nature Physics.

The first quantum computers - which will harness the strange behaviour of subatomic particles to far outperform even the most powerful supercomputers - are on the horizon. However, leveraging their full potential will require a way to network them: a quantum internet. Channels of light that transmit quantum information are promising candidates for a quantum internet, and currently there is no better quantum light source than the semiconductor quantum dot: tiny crystals that are essentially artificial atoms.

However, one thing stands in the way of quantum dots and a quantum internet: the ability to store quantum information temporarily at staging posts along the network.

"The solution to this problem is to store the fragile quantum information by hiding it in the cloud of 100,000 atomic nuclei that each quantum dot contains, like a needle in a haystack," said Professor Mete Atatüre from Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory, who led the research. "But if we try to communicate with these nuclei like we communicate with bits, they tend to 'flip' randomly, creating a noisy system."

The cloud of quantum bits contained in a quantum dot don't normally act in a collective state, making it a challenge to get information in or out of them. However, Atatüre and his colleagues showed in 2019 that when cooled to ultra-low temperatures also using light, these nuclei can be made to do 'quantum dances' in unison, significantly reducing the amount of noise in the system.

Now, they have shown another fundamental step towards storing and retrieving quantum information in the nuclei. By controlling the collective state of the 100,000 nuclei, they were able to detect the existence of the quantum information as a 'flipped quantum bit' at an ultra-high precision of 1.9 parts per million: enough to see a single bit flip in the cloud of nuclei.

"Technically this is extremely demanding," said Atatüre, who is also a Fellow of St John's College. "We don't have a way of 'talking' to the cloud and the cloud doesn't have a way of talking to us. But what we can talk to is an electron: we can communicate with it sort of like a dog that herds sheep."

Using the light from a laser, the researchers are able to communicate with an electron, which then communicates with the spins, or inherent angular momentum, of the nuclei.

By talking to the electron, the chaotic ensemble of spins starts to cool down and rally around the shepherding electron; out of this more ordered state, the electron can create spin waves in the nuclei.

"If we imagine our cloud of spins as a herd of 100,000 sheep moving randomly, one sheep suddenly changing direction is hard to see," said Atatüre. "But if the entire herd is moving as a well-defined wave, then a single sheep changing direction becomes highly noticeable."

In other words, injecting a spin wave made of a single nuclear spin flip into the ensemble makes it easier to detect a single nuclear spin flip among 100,000 nuclear spins.

Using this technique, the researchers are able to send information to the quantum bit and 'listen in' on what the spins are saying with minimal disturbance, down to the fundamental limit set by quantum mechanics.

"Having harnessed this control and sensing capability over this large ensemble of nuclei, our next step will be to demonstrate the storage and retrieval of an arbitrary quantum bit from the nuclear spin register," said co-first author Daniel Jackson, a PhD student at the Cavendish Laboratory.

"This step will complete a quantum memory connected to light - a major building block on the road to realising the quantum internet," said co-first author Dorian Gangloff, a Research Fellow at St John's College.

Besides its potential usage for a future quantum internet, the technique could also be useful in the development of solid-state quantum computing.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported in part by the European Research Council (ERC), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and the Royal Society.

[Images and video available: see notes to editors]

Wasps provide crucial support to their extended families by babysitting at neighbouring nests, according to new research by a team of biologists from the universities of Bristol, Exeter and UCL published today [15 February] in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

The findings suggest that animals should often seek to help more distant relatives if their closest kin are less in need.

Dr Patrick Kennedy, lead author and Marie Curie research fellow in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol, said: "These wasps can act like rich family members lending a hand to their second cousins. If there's not much more you can do to help your immediate family, you can ...

Feathers are a sleek, intricate evolutionary innovation that makes flight possible for birds, but in addition to their stiff, aerodynamic feathers used for flight, birds also keep a layer of soft, fluffy down feathers between their bodies and their outermost feathers to regulate body temperature.

Using the Smithsonian's collection of 625,000 bird specimens, Sahas Barve, a Peter Buck Fellow at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, led a new study to examine feathers across 249 species of Himalayan songbirds, finding that birds living at higher elevations have more of the fluffy down--the type of feathers humans stuff their jackets with--than birds from lower elevations. Published ...

Ciliopathies are genetic disorders caused by defects in the structure and function of cilia, microtubule-based organelles present on the surface of almost every cell in the human body which play crucial roles in cell signalling. Ciliopathies present a wide range of often severe clinical symptoms, frequently affecting the head and face and leading to conditions such as cleft palate and micrognathia (an underdeveloped lower jaw that can impair feeding and breathing). While we understand many of the genetic causes of human ciliopathies, they are only half the story: the question remains as to why, at a cellular level, defective cilia cause developmental craniofacial abnormalities. Researchers have now discovered that ciliopathic micrognathia in an animal model results from abnormal skeletal ...

Years of suffering and billions of euro in global health care costs, arising from osteoporosis-related bone fractures, could be eliminated using big data to target vulnerable patients, according to researchers at Lero, the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software.

A study of 36,590 patients who underwent bone mineral density scans in the West of Ireland between January 2000 and November 2018, found that many fractures are potentially preventable by identifying those at greatest risk before they fracture, and initiating proven, safe, low-cost effective interventions.

The multi-disciplinary study, ...

Long held in a private collection, the newly analysed tooth of an approximately 9-year-old Neanderthal child marks the hominin's southernmost known range. Analysis of the associated archaeological assemblage suggests Neanderthals used Nubian Levallois technology, previously thought to be restricted to Homo sapiens.

With a high concentration of cave sites harbouring evidence of past populations and their behaviour, the Levant is a major centre for human origins research. For over a century, archaeological excavations in the Levant have produced human ...

A recent study finds that the invasive spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) prefers to lay its eggs in places that no other spotted wing flies have visited. The finding raises questions about how the flies can tell whether a piece of fruit is virgin territory - and what that might mean for pest control.

D. suzukii is a fruit fly that is native to east Asia, but has spread rapidly across North America, South America, Africa and Europe over the past 10-15 years. The pest species prefers to lay its eggs in ripe fruit, which poses problems for fruit growers, since consumers don't want to buy infested fruit.

To avoid consumer rejection, there are extensive measures in place to avoid infestation, and to prevent infested ...

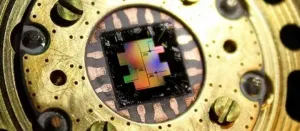

Aalto researchers have used an IBM quantum computer to explore an overlooked area of physics, and have challenged 100 year old cherished notions about information at the quantum level.

The rules of quantum physics - which govern how very small things behave - use mathematical operators called Hermitian Hamiltonians. Hermitian operators have underpinned quantum physics for nearly 100 years but recently, theorists have realized that it is possible to extend its fundamental equations to making use of Hermitian operators that are not Hermitian. The new equations describe a universe with its own peculiar set of rules: for example, by looking in the ...

It was tens of miles wide and forever changed history when it crashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

The Chicxulub impactor, as it's known, left behind a crater off the coast of Mexico that spans 93 miles and goes 12 miles deep. Its devastating impact brought the reign of the dinosaurs to an abrupt and calamitous end by triggering their sudden mass extinction, along with the end of almost three-quarters of the plant and animal species then living on Earth.

The enduring puzzle has always been where the asteroid or comet that set off the destruction originated, and how it came to strike the Earth. And ...

The UK's commercial fishing industry is currently experiencing a number of serious challenges.

However, a study by the University of Plymouth has found that managing the density of crab and lobster pots at an optimum level increases the quality of catch, benefits the marine environment and makes the industry more sustainable in the long term.

Published today in Scientific Reports, a journal published by the Nature group, the findings are the result of an extensive and unprecedented four-year field study conducted in partnership with local fishermen off the coast of southern England.

Over a sustained period, researchers exposed sections of the seabed to differing densities of pot fishing and monitored any impacts using a combination of underwater videos and catch ...

It forever changed history when it crashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

The Chicxulub impactor, as it's known, left behind a crater off the coast of Mexico that spans 93 miles and runs 12 miles deep. Its devastating impact brought the reign of the dinosaurs to an abrupt and calamitous end by triggering their sudden mass extinction, along with the end of almost three-quarters of the plant and animal species living on Earth.

The enduring puzzle: Where did the asteroid or comet originate, and how did it come to strike Earth? Now, a pair of researchers at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian believe they have the answer.

In a study published today in Nature's Scientific Reports, Harvard University ...