INFORMATION:

Funding and support for this research were provided by the Smithsonian.

Higher elevation birds sport thicker down "jackets" to survive the cold

Study of Himalayan songbirds in museum collections is first step toward using feathers to predict the effects of climate change for birds in extreme environments

2021-02-15

(Press-News.org) Feathers are a sleek, intricate evolutionary innovation that makes flight possible for birds, but in addition to their stiff, aerodynamic feathers used for flight, birds also keep a layer of soft, fluffy down feathers between their bodies and their outermost feathers to regulate body temperature.

Using the Smithsonian's collection of 625,000 bird specimens, Sahas Barve, a Peter Buck Fellow at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, led a new study to examine feathers across 249 species of Himalayan songbirds, finding that birds living at higher elevations have more of the fluffy down--the type of feathers humans stuff their jackets with--than birds from lower elevations. Published on Feb. 15 in the journal Ecography, the study also finds that smaller-bodied birds, which lose heat faster than larger birds, tend to have longer feathers in proportion to their body size and thus a thicker layer of insulation.

Finding such a clear pattern across so many species underscores how important feathers are to a bird's ability to adapt to its environment and suggests that adding down may be a strategy common to all songbirds, or passerines as they are known to researchers. Furthermore, finding that birds from colder environments tend to have more down may one day help researchers predict which birds are most vulnerable to climate change simply by studying their feathers.

"The Himalayas are seeing some of the fastest rates of warming on Earth," Barve said. "At the same time, climate change is driving an increase in the frequency and intensity of extremely cold events like snowstorms. Being able to accurately predict the temperatures a bird can withstand could give us a new tool to predict how certain species might respond to climate change."

The research was inspired by a tiny bird called a goldcrest during a frigid morning of field work in the Sho-kharkh forest of the Himalayas. Barve found himself wondering how this bird, which weighs about the same as a teaspoon of sugar, was able to flit about the treetops in icy air that was already numbing his fingers. Shoving his hands back into the pockets of his thick down jacket, the question that formed in Barve's mind was "Do Himalayan birds wear down jackets?"

To answer that question, Barve and his co-authors used a microscope to take photos of the chest feathers of 1,715 specimens from the Smithsonian's collections representing 249 species from the cold, high-altitude Himalayan Mountains. Then, Barve and his co-authors used those super-detailed photos to determine exactly how long each feather's downy section was relative to its total length. The team was able to do that by looking at the fluffy downy section of each feather close to its base when compared to the streamlined ends of most birds' feathers.

After meticulously logging the relative lengths of all those downy sections, Barve analyzed the results and found that the smallest birds and the birds from the highest elevations, where temperatures are at their coldest, tended to have the highest proportion of down on their body feathers. The analysis showed that high-elevation birds had up to 25% more down in their feathers, and the smallest bird had feathers that were three times as long as the largest birds, proportionately to their body size.

Past research suggested that birds from colder habitats sported added downy insulation, but Barve said this is the first study to analyze this pattern for such a large number of species in cold environments and across 15,000 feet of elevation.

"Seeing this correlation across so many species makes our findings more general and lets us say these results suggest all passerine birds may show this pattern," Barve said. "And we never would have been able to look at so many different species and get at this more general pattern of evolution without the Smithsonian's collections."

Carla Dove, who runs the museum's Feather Identification Lab and contributed to the study, said she was excited to work together with Barve to use the Smithsonian's collections in a new way. "Sahas looked at more than 1,700 specimens. Having them all in one place in downtown Washington, D.C., as opposed to having to go to the Himalayas and study these birds in the wild, obviously makes a big difference. It allowed him to gather the data he needed quickly before the COVID lockdowns swept the globe, and then work on the analysis remotely."

Barve said he is following up this study with experiments looking into just how much insulation birds get from their feathers and then will tie that to the feather's structure and proportion of down. One day, Barve aims to develop a model that will allow scientists to look at the structure of a feather and predict how much insulation it gives the bird--a capability that could help researchers identify species vulnerable to climate change.

Dove said the potential to use these results to eventually understand how some birds might cope with climate change highlights the importance of museum collections. "We have more than 620,000 bird specimens collected over the past 200 years waiting for studies like this. We don't know what our specimens will be used for down the line; that's why we have to maintain them and keep enhancing them. These specimens from the past can be used to predict the future."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Avian insights into human ciliopathies

2021-02-15

Ciliopathies are genetic disorders caused by defects in the structure and function of cilia, microtubule-based organelles present on the surface of almost every cell in the human body which play crucial roles in cell signalling. Ciliopathies present a wide range of often severe clinical symptoms, frequently affecting the head and face and leading to conditions such as cleft palate and micrognathia (an underdeveloped lower jaw that can impair feeding and breathing). While we understand many of the genetic causes of human ciliopathies, they are only half the story: the question remains as to why, at a cellular level, defective cilia cause developmental craniofacial abnormalities. Researchers have now discovered that ciliopathic micrognathia in an animal model results from abnormal skeletal ...

Improved use of databases could save billions of euro in health care costs

2021-02-15

Years of suffering and billions of euro in global health care costs, arising from osteoporosis-related bone fractures, could be eliminated using big data to target vulnerable patients, according to researchers at Lero, the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software.

A study of 36,590 patients who underwent bone mineral density scans in the West of Ireland between January 2000 and November 2018, found that many fractures are potentially preventable by identifying those at greatest risk before they fracture, and initiating proven, safe, low-cost effective interventions.

The multi-disciplinary study, ...

Neanderthals and Homo sapiens used identical Nubian technology

2021-02-15

Long held in a private collection, the newly analysed tooth of an approximately 9-year-old Neanderthal child marks the hominin's southernmost known range. Analysis of the associated archaeological assemblage suggests Neanderthals used Nubian Levallois technology, previously thought to be restricted to Homo sapiens.

With a high concentration of cave sites harbouring evidence of past populations and their behaviour, the Levant is a major centre for human origins research. For over a century, archaeological excavations in the Levant have produced human ...

Invasive flies prefer untouched territory when laying eggs

2021-02-15

A recent study finds that the invasive spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) prefers to lay its eggs in places that no other spotted wing flies have visited. The finding raises questions about how the flies can tell whether a piece of fruit is virgin territory - and what that might mean for pest control.

D. suzukii is a fruit fly that is native to east Asia, but has spread rapidly across North America, South America, Africa and Europe over the past 10-15 years. The pest species prefers to lay its eggs in ripe fruit, which poses problems for fruit growers, since consumers don't want to buy infested fruit.

To avoid consumer rejection, there are extensive measures in place to avoid infestation, and to prevent infested ...

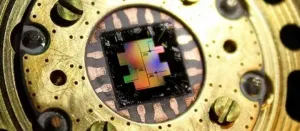

New physics rules tested on quantum computer

2021-02-15

Aalto researchers have used an IBM quantum computer to explore an overlooked area of physics, and have challenged 100 year old cherished notions about information at the quantum level.

The rules of quantum physics - which govern how very small things behave - use mathematical operators called Hermitian Hamiltonians. Hermitian operators have underpinned quantum physics for nearly 100 years but recently, theorists have realized that it is possible to extend its fundamental equations to making use of Hermitian operators that are not Hermitian. The new equations describe a universe with its own peculiar set of rules: for example, by looking in the ...

The comet that killed the dinosaurs

2021-02-15

It was tens of miles wide and forever changed history when it crashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

The Chicxulub impactor, as it's known, left behind a crater off the coast of Mexico that spans 93 miles and goes 12 miles deep. Its devastating impact brought the reign of the dinosaurs to an abrupt and calamitous end by triggering their sudden mass extinction, along with the end of almost three-quarters of the plant and animal species then living on Earth.

The enduring puzzle has always been where the asteroid or comet that set off the destruction originated, and how it came to strike the Earth. And ...

Managing crab and lobster catches could offer long-term benefits

2021-02-15

The UK's commercial fishing industry is currently experiencing a number of serious challenges.

However, a study by the University of Plymouth has found that managing the density of crab and lobster pots at an optimum level increases the quality of catch, benefits the marine environment and makes the industry more sustainable in the long term.

Published today in Scientific Reports, a journal published by the Nature group, the findings are the result of an extensive and unprecedented four-year field study conducted in partnership with local fishermen off the coast of southern England.

Over a sustained period, researchers exposed sections of the seabed to differing densities of pot fishing and monitored any impacts using a combination of underwater videos and catch ...

Comet or asteroid: What killed the dinosaurs and where did it come from?

2021-02-15

It forever changed history when it crashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

The Chicxulub impactor, as it's known, left behind a crater off the coast of Mexico that spans 93 miles and runs 12 miles deep. Its devastating impact brought the reign of the dinosaurs to an abrupt and calamitous end by triggering their sudden mass extinction, along with the end of almost three-quarters of the plant and animal species living on Earth.

The enduring puzzle: Where did the asteroid or comet originate, and how did it come to strike Earth? Now, a pair of researchers at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian believe they have the answer.

In a study published today in Nature's Scientific Reports, Harvard University ...

A machine-learning approach to finding treatment options for Covid-19

2021-02-15

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck in early 2020, doctors and researchers rushed to find effective treatments. There was little time to spare. "Making new drugs takes forever," says Caroline Uhler, a computational biologist in MIT's Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and the Institute for Data, Systems and Society, and an associate member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. "Really, the only expedient option is to repurpose existing drugs."

Uhler's team has now developed a machine learning-based approach to identify drugs already on the market that could ...

Commuters are inhaling unacceptably high levels of carcinogens

2021-02-15

A new study finds that California's commuters are likely inhaling chemicals at levels that increase the risk for cancer and birth defects.

As with most chemicals, the poison is in the amount. Under a certain threshold of exposure, even known carcinogens are not likely to cause cancer. Once you cross that threshold, the risk for disease increases.

Governmental agencies tend to regulate that threshold in workplaces. However, private spaces such as the interior of our cars and living rooms are less studied and less regulated.

Benzene and formaldehyde -- both used in automobile manufacturing -- are known to cause cancer at or above certain levels of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

[Press-News.org] Higher elevation birds sport thicker down "jackets" to survive the coldStudy of Himalayan songbirds in museum collections is first step toward using feathers to predict the effects of climate change for birds in extreme environments