USC biologists devise new way to assess carbon in the ocean

2021-02-16

(Press-News.org) A new USC study puts ocean microbes in a new light with important implications for global warming.

The study, published Tuesday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides a universal accounting method to measure how carbon-based matter accumulates and cycles in the ocean. While competing theories have often been debated, the new computational framework reconciles the differences and explains how oceans regulate organic carbon across time.

Surprisingly, most of the action involving carbon occurs not in the sky but underfoot and undersea. The Earth's plants, oceans and mud store five times more carbon than the atmosphere. It accumulates in trees and soil, algae and sediment, microorganisms and seawater.

"The ocean is a huge carbon reservoir with the potential to mitigate or enhance global warming," said Naomi Levine, senior author of the study and assistant professor in the biological sciences department at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. "Carbon cycling is critical for understanding global climate because it sets the temperature, which in turn sets climate and weather patterns. By predicting how carbon cycling and storage works, we can better understand how climate will change in the future."

Processes governing how organic matter -- decaying plant and animal matter in the environment akin to the material gardeners add to soil -- accumulates are critical to the Earth's carbon cycle. However, scientists don't have good tools to predict when and how organic matter piles up. That's a problem because a better reconciling of organic carbon can inform computer models that forecast global warming and support public policy.

New USC framework can gauge organic carbon increases in the ocean

In recent years, scientists have offered three competing theories to explain how organic matter accumulates, and each has its limitations. For example, one idea is some organic matter is intrinsically persistent, similar to an orange peel. Sometimes carbon is too diluted so microbes can't locate and eat it, as if they're trying to find a single yellow jellybean in a jar full of white ones. And sometimes, the right microbe isn't in the right place at the right time to intercept organic matter due to environmental conditions.

While each theory explains some observations, the USC study shows how this new framework can provide a much more comprehensive picture and explain the ecological dynamics important for organic matter accumulation in the ocean. The solution has wide utility.

For example, it can help interpret data from any condition in the ocean. When linked into a full ecosystem model, the framework accounts for diverse types of microbes, water temperature, nutrients, reproduction rates, sunlight and heat, ocean depth and more. Through its ability to represent diverse environmental conditions worldwide, the model can predict how organic carbon will accumulate in various complex scenarios -- a powerful tool at a time when oceans are warming and the Earth is rapidly changing.

"Predicting why organic carbon accumulates has been an unsolved challenge," said Emily Zakem, a study co-author and postdoctoral scholar at USC Dornsife. "We show that the accumulation of carbon can be predicted using this computational framework."

Assessing the past -- and the future -- of Earth's oceans

The tool can also potentially be used to model past ocean conditions as a predictor of what may be in store for the Earth as the planet warms largely due to manmade greenhouse gas emissions.

Specifically, the model is capable of looking at how marine microbes can flip the world's carbon balance. The tool can show how microbes process organic matter in the water column throughout a given year, as well as at millennial timescales. Using that feature, the model confirms -- as has been previously predicted -- that microbes will consume more organic matter and rerelease it as carbon dioxide as the ocean warms, which ultimately will increase atmospheric carbon concentrations and increase warming. Moreover, the study says this phenomenon can occur rapidly, in a non-linear way, once a threshold is reached -- a possible explanation for some of the whipsaw climate extremes that occurred in Earth's distant past.

"This suggests that changes in climate, such as warming, may result in large changes in organic carbon stores and that we can now generate hypotheses as to when this might occur," Levine said.

Finally, the research paper says the new tool can model how carbon moves through soil and sediment in the terrestrial environment, too, though those applications were not part of the study.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Zakem and Levine, the study's authors included B.B. Cael of the National Oceanography Centre in England.

Funding for the research team comes from the Simons Foundation, Simons Collaboration on Principles of Microbial Ecology (#542389) to Levine; the Simons Postdoctoral Fellowship in Marine Microbial Ecology to Zakem; a National Environmental Research Council grant (#NER015953-1) and a European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program grant (#820989) to Cael.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-16

The mitochondrial ribosome is an intricate machine that translates the organellar genome into functional proteins. The formation of the mitochondrial ribosome is a hierarchical process involving dozens of different components. The newly published cryo-EM study by Tobiasson et al in the EMBO Journal characterized a key step in this process.

A complex of 2.2 MegaDalton representing a rare state of assembly of the large subunit was isolated from a model organism Trypanosoma brucei. Since the state was identified in only 3.5 % of the complexes, five cryo-EM datasets had to be collected at the SciLifeLab facility and ESRF in Grenoble and combined together.

The resulting structure revealed ...

2021-02-16

A new study published in Nature Communications suggests that the extinction of North America's largest mammals was not driven by overhunting by rapidly expanding human populations following their entrance into the Americas. Instead, the findings, based on a new statistical modelling approach, suggest that populations of large mammals fluctuated in response to climate change, with drastic decreases of temperatures around 13,000 years ago initiating the decline and extinction of these massive creatures. Still, humans may have been involved in more complex and indirect ways than simple models of overhunting suggest.

Before around 10,000 years ago, North America was ...

2021-02-16

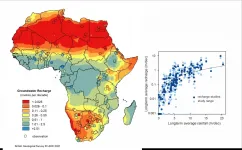

Effective governance and investment decisions need to be informed by reliable data, not only about where groundwater exists, but also the rate at which groundwater is replenished. For the first time using ground measurements, a recent study has quantified groundwater recharge rates across the whole of Africa - averaged over a fifty-year period - which will help to identify the sustainability of water resources for African nations.

The study, led by the British Geological Survey and involving an international team from the UK, South Africa, France, Nigeria, and America, developed a dataset of 134 existing recharge studies ...

2021-02-16

Gender equity and racial diversity in medicine can promote creative solutions to complex health problems and improve the delivery of high-quality care, argue authors in an analysis in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

"[T]here is no excuse for not working to change the climate and environment of the medical profession so that it is welcoming of diversity," writes lead author Dr. Andrea Tricco, Knowledge Translation Program, Unity Health, and the University of Toronto, with coauthors. "The medical profession should be professional, be collegial, show mutual respect, and facilitate the full potential and contribution of all genders, races, ethnicities, religions and nationalities for the benefit of patient ...

2021-02-16

NASA, in collaboration with other leading space agencies, aims to send its first human missions to Mars in the early 2030s, while companies like SpaceX may do so even earlier. Astronauts on Mars will need oxygen, water, food, and other consumables. These will need to be sourced from Mars, because importing them from Earth would be impractical in the long term. In Frontiers in Microbiology, scientists show for the first time that Anabaena cyanobacteria can be grown with only local gases, water, and other nutrients and at low pressure. This makes it much easier to develop sustainable biological life support systems.

"Here we show that cyanobacteria can use gases available in the Martian atmosphere, at a low total pressure, as their source of carbon and nitrogen. Under these conditions, ...

2021-02-16

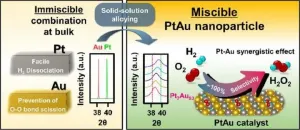

Hydrogen peroxide is used as a disinfectant, after dilution in water, to treat wounds. It is widely used across the industry as an eco-friendly oxidizing agent for impurity removal from semiconductors, waste treatment, etc. Currently, it is mainly produced by the sequential hydrogenation and oxidation of anthraquinone (AQ). However, this process is not only energy intensive and requires large-scale facilities, but AQ is also toxic.

As an alternative to the AQ process, hydrogen peroxide direct synthesis from hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) using a palladium (Pd) catalyst was proposed. However, the commercialization of the technology ...

2021-02-16

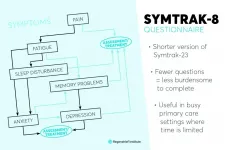

INDIANAPOLIS -- Researchers from Regenstrief Institute and Indiana University School of Medicine have developed and validated a short questionnaire to help patients report symptoms and assist healthcare providers in assessing the severity of symptoms, and in monitoring and adjusting treatment accordingly.

The tool, called SymTrak-8, is a shorter version of the SymTrak-23. The questionnaire tracks symptoms such as pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, memory problems, anxiety and depression in older adults, enabling clinicians to provide better care for the diseases causing the symptoms.

"These symptoms are commonly reported in primary care, but they can be a sign of a variety of different diseases, so tracking them is important," said Kurt ...

2021-02-16

Teens may be more likely to use marijuana after legalization for adult recreational use

PISCATAWAY, NJ - Adolescents who live in California may be more likely to use marijuana since adult recreational marijuana use was legalized in 2016, according to a new report in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs.

"The apparent increase in marijuana use among California adolescents after recreational marijuana legalization for adult use in 2016 is surprising given the steady downward trend in marijuana use during years before legalization," says lead researcher Mallie J. ...

2021-02-16

A new first-of-its-kind study has questioned whether pub operators can effectively and consistently prevent COVID-19 transmission - after researchers observed risks arising in licensed premises last summer.

Led by the University of Stirling, the research was conducted in May to August last year in a wide range of licensed premises which re-opened after a nationwide lockdown, and were operating under detailed guidance from government intended to reduce transmission risks.

While observed venues had made physical and operational modifications on re-opening, ...

2021-02-16

A technology that is widely used by commercial genetic testing companies is "extremely unreliable" in detecting very rare variants, meaning results suggesting individuals carry rare disease-causing genetic variants are usually wrong, according to new research published in the BMJ.

After hearing of cases where women had surgery scheduled after wrongly being told they had very rare genetic variations in the gene BRCA1 that could significantly increase risk of breast cancer, a team at the University of Exeter conducted a large-scale analysis of the technology using data from nearly 50,000 people. They found that the technology wrongly identified ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] USC biologists devise new way to assess carbon in the ocean