(Press-News.org) Humans inhabit an incredible range of environments across the globe, from arid deserts to frozen tundra, tropical rainforests, and some of the highest peaks on Earth. Indigenous populations that have lived in these extreme environments for thousands of years have adapted to confront the unique challenges that they present. Approximately 2% of people worldwide live permanently at high altitudes of over 2,500 meters (1.5 miles), where oxygen is sparse, UV radiation is high, and temperatures are low. Native Andeans, Tibetans, Mongolians, and Ethiopians exhibit adaptations that improve their ability to survive such conditions. Andeans, for example, display increased chest circumference, elevated oxygen saturation, and a low hypoxic ventilatory response, enabling them to thrive at exceptionally high elevations. While it is clear that there is a genetic component to these adaptations, exposure to high altitudes during early development is also known to play a role, although the underlying mechanism for this remains poorly understood. In a new study in Genome Biology and Evolution titled "Genome-Wide Epigenetic Signatures of Adaptive Developmental Plasticity in the Andes", Ainash Childebayeva, a doctoral student at the University of Michigan at the time of the study, and her colleagues sought to answer this question by studying members of the Peruvian Quechua, who live at high altitudes in the Andes. Their work reveals that mechanisms like DNA methylation may be involved in adaptation to high altitudes, and their findings have potential implications for the long-term health of those living at such heights.

Adaptations are typically thought of as genetic changes leading to the manifestation of a certain physiological trait, or phenotype. In a phenomenon known as developmental adaptation or adaptive plasticity, however, a certain genetic background merely serves as the prerequisite, and exposure to a certain environmental stimulus--generally during early development--is further required for the trait to be expressed. According to Childebayeva and co-authors, "There are several examples of Andean high-altitude adaptive phenotypes where developmental adaptation plays a key role in the manifestation of the adult phenotype." For example, Andeans who are lifelong residents of high altitude display greater lung volumes than those of Andean ancestry who were born and raised at sea level.

To reveal the biological mechanisms enabling this interplay between environment, development, and genetics, Childebayeva and her collaborators focused on epigenetics, the study of modifications that alter the DNA molecule without changing the order of nucleotides. Methylation is one type of epigenetic mark in which a methyl group is added to the cytosine nucleotides contained in DNA. Methylation suppresses the transcription of associated genes, thereby influencing an organism's biology by regulating protein expression. Importantly, DNA methylation patterns are established prenatally and in the early postnatal period, after which they remain relatively stable, providing an early developmental window during which environmental exposures may help shape an individual's phenotype.

The Quechua, an indigenous group native to Peru, have lived on the Andean Altiplano at an average elevation of 12,000 feet (over 3,600 m) for 11,000 years. In order to investigate the potential role of epigenetics in developmental adaptation to high altitudes, the study's authors evaluated DNA methylation patterns across the genome in three groups of Peruvian Quechua with different altitude exposures: high-altitude Quechua, who had lifetime exposure to high altitude; migrant Quechua, who were born at high altitude but subsequently moved to low altitudes; and low-altitude Quechua, who were lifelong residents of low altitude, despite the fact that their parents and both sets of grandparents were of highland Quechua ancestry. By comparing which DNA positions were methylated in high-altitude and migrant Quechua, who shared early childhood exposure to high altitudes, with those methylated in low-altitude Quechua, who shared ancestry but were not exposed in childhood, the authors were able to untangle the effects of developmental exposure to altitude and genetics.

The study identified specific positions and regions of DNA in which methylation was associated with either lifelong or early altitude exposure. Some of these regions were associated with genes previously linked to high-altitude adaptation, such as those involved in red blood cell production, glucose metabolism, and skeletal muscle development. In particular, some of these genes have been previously implicated in scans of genetic adaptations in other high-altitude populations, such as Tibetans and Mongolians, indicating that both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms may be acting on similar pathways in multiple high-altitude groups. These findings support the idea that epigenetics are involved in developmental adaptation and that early developmental exposures can have persistent impacts on DNA methylation patterns.

The study's findings also have implications for the health of high-altitude populations. For example, two of the methylated regions associated with high altitude overlapped genes linked to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a condition characterized by irreversible fibrosis of the lung that is known to be associated with hypoxia (lack of oxygen). This suggests that high-altitude populations may have different susceptibilities to this condition or distinct pathological features compared to low-altitude populations. Moreover, the authors estimated the "epigenetic age" of the three groups of Quechua, a phenomenon that reflects the state of the epigenetic maintenance system and can serve as a marker of premature biological aging. They found that those with lifelong exposure to high altitude showed accelerated epigenetic aging compared to those who were lifelong residents of low altitude, likely reflecting the strain that hypoxia places on the cellular machinery.

According to Childebayeva, the resources and collaborators at the Cerro de Pasco High-Altitude laboratory, associated with the Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, Peru, were key to the completion of this project. Researchers have been studying high-altitude adaptation in Cerro de Pasco for almost one hundred years, with one of the first studies taking place in 1921-1922. Now in the Department of Archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Human History, Childebayeva hopes to one day extend this work by studying developmental adaptation in the high-altitude populations of Central Asia, shedding further light on the epigenetic mechanisms that allow humans to push the upper limits of high-altitude habitation.

INFORMATION:

New study from Warwick Medical School examined the effectiveness of three alternatives to CPR, concluding that none were beneficial

First comprehensive systematic review of evidence on precordial thump, percussion pacing and cough CPR - all of which have fallen out of routine practice

Precordial thump is often portrayed in television and film, and cough CPR misinformation circulates frequently on social media - but neither are effective

Reaffirms CPR as the 'gold standard' technique when assisting someone experiencing a cardiac arrest

A technique frequently portrayed in dramatic resuscitation scenes in television ...

Scientists created a framework to test the predictions of biological optimality theories, including evolution.

Evolution adapts and optimizes organisms to their ecological niche. This could be used to predict how an organism evolves, but how can such predictions be rigorously tested? The Biophysics and Computational Neuroscience group led by professor Gašper Tkačik at the Institute of Science and Technology (IST) Austria has now created a mathematical framework to do exactly that.

Evolutionary adaptation often finds clever solutions to challenges posed by different environments, from how to survive in the dark depths of the oceans to creating intricate organs such as an eye or an ear. But can we mathematically predict these outcomes?

This is ...

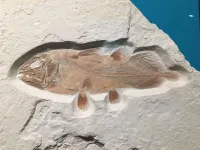

Fossilised remains of a fish that grew as big as a great white shark and the largest of its type ever found have been discovered by accident.

The new discovery by scientists from the University of Portsmouth is a species of the so-called 'living fossil' coelacanths which still swim in the seas, surviving the extinction that killed off the dinosaurs.

The discovery was purely serendipitous. Professor David Martill, a palaeontologist from the University's School of the Environment, Geography and Geosciences, had been asked to identify a large ...

In plants, the "meristem" refers to a type of tissue comprising undifferentiated cells from which various other plant organs can develop through cell division and differentiation. These "plant stem cells" give rise to shoots, leaves and roots, but also spikes and flowers.

The research team including members of the Cluster of Excellence on Plant Sciences CEPLAS investigated the function of a gene responsible for the different spike forms of wheat and barley. This gene controls the activity of the spike and floret meristems and thus the number of spikelet ...

The research team that developed a biosensor that first recorded that a distinct gradient of the plant growth hormone gibberellin correlated with plant cell size has now revealed how this distribution pattern is created in roots.

Starting when a plant embryo forms within a seed and continuing throughout the plant lifecycle, undifferentiated stem cells undergo radical transformations into specialised root, stem, leaf and reproductive organ cells. This transformation relies on a suite of molecules called phytohormones that, much like human hormones, can move between cells and tissues and trigger distinct biological processes across the bodyplan. While it was not known at the time, mutations involving the gibberellin class of ...

PITTSBURGH, Feb. 15, 2021 - Why do patients who receive antipsychotic medications to manage schizophrenia and bipolar disorder quickly gain weight and develop prediabetes and hyperinsulemia? The question remained a mystery for decades, but in a paper published today in Translational Psychiatry, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine finally cracked the enigma.

Antipsychotic drugs, scientists showed, not only block dopamine signaling in the brain but also in the pancreas, leading to uncontrolled production of blood glucose-regulating hormones and, eventually, obesity and diabetes.

"There are dopamine theories of schizophrenia, drug addiction, depression and neurodegenerative disorders, and we are presenting a dopamine theory of metabolism," said lead ...

For more than a decade, governments in countries across the world have made significant progress to expand their protected areas network to conserve the planet's biodiversity. According to a new study published in the journal Global Change Biology, the locations of these protected areas do not take into account the potential long-term effects of climate change in these protected areas.

Creating and managing protected areas, such as national parks, is key for biodiversity conservation. As the climate changes, however, species will disperse in order to maintain their specific habitat needs. Species that were in protected areas ...

Almost half the patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) require invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), a medical procedure that guarantees a sufficient supply of oxygen to their organs and tissues. The therapy involves connecting patients to a machine that substitutes their spontaneous breathing. In recent months it has been in general use in intensive-care patients affected by COVID-19.

Although it can often save a patient's life, invasive mechanical ventilation is not risk-free: there can be accidental injury during intubation or extubation or the muscles ...

A NEW study from the University of Chichester has shed light on how people coped psychologically with the sudden and life-changing disruption caused by COVID-19.

This new publication, by Chichester's Professor Laura Ritchie and PhD candidate Benjamin Sharpe, in collaboration with Professor Daniel Cervone of the University of Illinois at Chicago, provides a unique snapshot into people's understanding of their goals and self-beliefs amidst a shared, unexpected alteration of the daily landscape during lockdown.

Ritchie and colleagues collected their ...

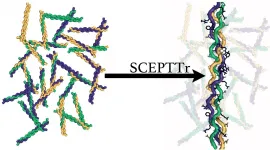

HOUSTON - (Feb. 15, 2021) - Collagen is the king of biological proteins, and now it has a SCEPTTr.

That's the handle of an algorithm developed by Rice University scientists who study natural and synthetic versions of collagen, which accounts for about a third of the body's proteins and forms the fibrous glue in skin, bones, muscles, tendons and ligaments.

The program -- full name, Scoring function for Collagen-Emulating-Peptides' Temperature of Transition -- accurately predicts the stability of collagen triple helices, the primary structure that forms fibrils.

The Rice team led by chemist and bioengineer Jeffrey ...