(Press-News.org) A toxin produced by bacteria as a defence mechanism causes mutations in target bacteria that could help them survive, according to a study published today in eLife.

The finding suggests that competitive encounters between bacterial cells could have profound consequences on the evolution of bacterial populations.

When bacterial cells come into contact, they often produce toxins as a defence mechanism. Although it is known that the bacteria producing these toxins have a competitive advantage, exactly how the toxins affect the recipient cells is less clear.

"Undergoing intoxication is not always detrimental for cells - there are scenarios in which encountering a toxin could provide a benefit, such as generating antibiotic resistance," explains lead author Marcos de Moraes, Postdoctoral Scholar at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, US. "We wanted to study the effects of a toxin that alters DNA beyond that of cell death and see how it impacts the surviving recipient cells it targets."

The team began by studying a toxin called DddA (double-stranded deaminase A), found in a bacterial species called Burkholderia cenocepacia. DddA removes chemical groups called amines from DNA, causing a specific change in the genetic code.

To understand how DddA kills bacterial cells, the team looked at how a large dose of the toxin affects chromosomes in Escherichia coli (E. coli). They found that DddA caused rapid disintegration of chromosomes and the breakdown of DNA replication. Additionally, when they sequenced the DNA before it had disintegrated, they found widespread mutations consistent with the types of chemical changes DddA can make.

Despite this ability to cause such damage, the team was surprised to find that DddA failed to kill the E. coli cells when it was delivered at natural levels by the producing bacterium. This led them to test whether DddA was naturally toxic against other bacterial species. They identified several species that were susceptible to DddA when delivered by Burkholderia cenocepacia, and set out to determine the mechanism. As they expected, they found the same accumulation of mutations and chromosome damage that occurred when a large dose of DddA was given to E. coli.

However, given that DddA failed to kill E. coli when delivered by the natural route, the team was keen to test whether sub-lethal exposure to DddA caused mutations that provide a benefit. They found that E. coli grown in competition with DddA-producing Burkholderia cenocepacia cells for one hour had a ten-fold increase in antibiotic-resistant cells compared to E. coli that was not exposed to DddA. When they sequenced the DNA of the resistant E. coli cells, they saw that resistance had been caused by the hallmark mutations that DddA generates.

They next looked at other bacterial cells that were resistant or sensitive to death when exposed to DddA delivered by Burkholderia cenocepacia. Among additional resistant organisms, the human pathogens Klebsiella pneumoniae and enterohemorrhagic E. coli had higher numbers of antibiotic-resistant cells when in contact with DddA, and had the hallmark mutation signatures of DddA damage. By contrast, in cells sensitive to killing by DddA, there was no increased level of mutations, and only 15% of antibiotic-resistant clones had mutation patterns similar to those caused by DddA. This suggests that mutations may be a rare outcome of DddA toxicity in sensitive species that survive intoxication, but additional study will be needed to support this association.

The team went on to characterise additional classes of DddA-like toxins and identified a related toxin from the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae. Although this toxin still makes the same pattern of chemical changes to DNA, it was found to act on single-stranded DNA - so the researchers called it single-strand DNA deaminase (SsdA). Structural analysis of SsdA1 confirmed its relationship within the same family of toxins as DddA, although it contains remarkable differences, prompting questions about its evolutionary origins.

"This study reveals that interbacterial toxins may be relevant contributors to bacterial genetic diversity in natural microbial communities, giving cells that survive the toxin a leg up in the rare - but critical - instances where those mutations provide a benefit," concludes senior author Joseph Mougous, Professor of Microbiology at the University of Washington, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. "This could be clinically relevant as well, where bacteria that possess these toxins are present and resistance to certain antibiotics requires a succession of mutations."

INFORMATION:

This study will be published in eLife's Special Issue on evolutionary medicine. For more information, visit https://elifesciences.org/inside-elife/bb34a238/special-issue-call-for-papers-in-evolutionary-medicine.

Media contact

Emily Packer,

Media Relations Manager

eLife

e.packer@elifesciences.org

+44 (0)1223 855373

About eLife

eLife is a non-profit organisation created by funders and led by researchers. Our mission is to accelerate discovery by operating a platform for research communication that encourages and recognises the most responsible behaviours. We aim to publish work of the highest standards and importance in all areas of biology and medicine, including Genetics and Genomics and Microbiology and Infectious Disease, while exploring creative new ways to improve how research is assessed and published. eLife receives financial support and strategic guidance from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society and Wellcome. Learn more at https://elifesciences.org/about.

To read the latest Genetics and Genomics research published in eLife, visit https://elifesciences.org/subjects/genetics-genomics.

And for the latest in Microbiology and Infectious Disease, see https://elifesciences.org/subjects/microbiology-infectious-disease.

To combat climate change, shifting from fossil fuels to clean and sustainable energy sources is imperative. A popular candidate in this regard is hydrogen, an eco-friendly fuel that produces only water when used. However, the efficient methods of hydrogen production are usually not eco-friendly. The eco-friendly alternative of splitting water with sunlight to produce hydrogen is inefficient and suffers from low stability of the photocatalyst (material that facilitates chemical reactions by absorbing light). How does one address the issue of developing a stable and efficient photocatalyst?

In a study recently published in Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, ...

Having a memory of past events enables us to take smarter decisions about the future. Researchers at the Max-Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization (MPI-DS) and the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have now identified how the slime mold Physarum polycephalum saves memories - although it has no nervous system.

The ability to store and recover information gives an organism a clear advantage when searching for food or avoiding harmful environments. Traditionally it has been attributed to organisms that have a nervous system.

A new study authored by Mirna Kramar (MPI-DS) and Prof. Karen Alim (TUM and MPI-DS) challenges this view by uncovering the surprising abilities of a highly dynamic, single-celled organism to store and ...

During ice ages, the global mean sea level falls because large amounts sea water are stored in the form of huge continental glaciers. Until now, mathematical models of the last ice age could not reconcile the height of the sea level and the thickness of the glacier masses: the so-called Missing Ice Problem. With new calculations that take into account crustal, gravitational and rotational perturbation of the solid Earth, an international team of climate researchers has succeeded in resolving the discrepancy, among them Dr. Paolo Stocchi from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ). The study, now published in the ...

During this unique study, a team of researchers led by Professor Jane Ogden from the University of Surrey investigated the impact of actively preparing or watching others prepare food (e.g., on a cooking show) versus distraction away from this focus. Researchers sought to understand how this may affect the amount of food consumed and influence the desire to continue eating.

To investigate this further, eighty female participants were recruited and assigned to one of four groups: active food preparation (preparing a cheese wrap within 10 minutes), video food preparation (watching a video of a researcher preparing a cheese wrap), distraction ...

University of Alberta researchers have found that limiting the amount of fat the body releases into the bloodstream from fat cells during heart failure could help improve outcomes for patients.

In a recent study published in the American Journal of Physiology, Jason Dyck, professor of pediatrics in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry and director of the U of A's Cardiovascular Research Centre, found that mice with heart failure that were treated with a drug blocking the release of fat into the bloodstream from fat cells saw less inflammation in the heart and throughout the body, and had better outcomes than a control group.

"Many people believe that, by definition, heart failure is only ...

New Orleans, LA - An LSU Health New Orleans School of Public Health study reports a positive association between social vulnerability and COVID-19 incidence at the census tract level and recommends that more resources be allocated to socially vulnerable populations to reduce the incidence of COVID-19. The findings are published in Frontiers in Public Health, available END ...

Gay men are more likely than lesbian women to face stigma and avoidant prejudice from their heterosexual peers due to the sound of their voice, a new study in the British Journal of Social Psychology reports. Researchers also found that gay men who believe they sound gay anticipate stigma and are more vigilant regarding the reactions of others.

During this unique study researchers from the University of Surrey investigated the role of essentialist beliefs -- the view that every person has a set of attributes that provide an insight into their identity -- of heterosexual, lesbian ...

In Wonderland, Alice drank a potion to shrink herself. In nature, some animal species shrink to escape the attention of human hunters, a process that takes from decades to millennia. To begin to understand the genetics of shrinking, scientists working at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama successfully extracted DNA from marine shells. Their new technique will not only shed light on how animals from lizards to lemurs shrink, it will reveal many other stories hidden in shells.

"Humans are unique as predators," said Alexis Sullivan, doctoral student at Penn ...

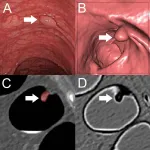

OAK BROOK, Ill. - A machine learning algorithm helps accurately differentiate benign and premalignant colorectal polyps on CT colonography scans, according to a study published in the journal Radiology.

Colorectal cancer is among the three most common causes of cancer-related death among men and women in industrialized countries. Most types of colorectal cancer originate from adenomatous polyps--gland-like growths on the mucous membrane lining the large intestine--that develop over several years. Early detection and removal of these precancerous polyps can reduce the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

During the last two decades, CT colonography emerged as a noninvasive ...

Peer review/observational study/people

In patients with severe COVID-19, the innate immune system overreacts. This overreaction may underlie the formation of blood clots (thrombi) and deterioration in oxygen saturation that affect the patients. This is shown in an Uppsala University study published in the journal Frontiers in Immunology.

Blood contains numerous proteins that constitute the body's primary barrier, by both recognising and destroying microorganisms, including SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19). These proteins are part of the intravascular innate immune system (IIIS), which consists of certain white blood cells, platelets and what are known as the cascade systems of the blood.

Only 5 ...