(Press-News.org) The cocktail of beneficial bacteria passed from mother to infant through breast milk changes significantly over time and could act like a daily booster shot for infant immunity and metabolism. The research, conducted by scientists from Montreal and Guatemala and published in Frontiers in Microbiology, has important implications for infant development and health.

Researchers discovered a range of microbiome species never before identified in human milk. Until now, relatively little was known about the role microbiome bacteria play in breast milk. These bacteria are thought to protect the infant gastrointestinal tract and improve aspects of long-term health, such as allergy prevention.

"Some bacterial species we observed in our sample breast milk had a common function in destroying foreign substances or xenobiotics and could play a role in protection against toxins and pollutants," says co-author Emmanuel Gonzalez, a bioinformatics specialist at McGill University. The discovery sheds light on how mothers help lay the foundation for infant immunity.

Differences between early and late lactation

To learn more about the human milk microbiome, the scientists analyzed breast milk samples using high-resolution imaging technology, originally pioneered by McGill University and the University of Montreal to detect bacteria on the International Space Station.

They analyzed breast milk samples of Mam-Mayan mothers living in eight remote rural communities in the Western Highlands of Guatemala. This gave them a unique window to observe the human milk microbiome over time, specifically between early and late lactation (6-46 days versus 109-184 days).

Unlike most mothers in North America, nearly all Mam-Mayan mothers breastfeed for the World Health Organization's recommended period of six months. In North America, only 26% of mothers do so. "This longer feeding time allowed us to observe important changes in the bacteria provided to infants over time, which could impact long-term health," says Gonzalez.

The genomic technology used by the scientists revealed a range of microbiome species shared among Mam-Mayan mothers, providing a glimpse of a diverse community of bacteria being passed on to infants.

"Studying microbiomes of diverse communities is important in order to understand the variation present in humans," says co-author Kristine Koski, an Associate Professor in the School of Human Nutrition at McGill. "Most human milk microbiome studies have been conducted with mothers from high income countries, generating an incomplete picture of the important bacteria passed to infants during early development."

Working alongside underrepresented communities will be essential in getting an accurate picture of the human milk microbiome and the factors that shape it, according to the scientists. They hope that these discoveries will help encourage more inclusive and more robust research.

INFORMATION:

About this study

"Distinct Changes Occur in the Human Breast Milk Microbiome Between Early and Established Lactation in Breastfeeding Guatemalan Mothers" by Gonzalez Emmanuel, Brereton Nicholas J. B., Li Chen, Lopez Leyva Lilian, Solomons Noel W., Agellon Luis B., Scott Marilyn E., and Koski Kristine G. was published in Frontiers in Microbiology.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.557180

About McGill University

Founded in Montreal, Quebec, in 1821, McGill University is Canada's top ranked medical doctoral university. McGill is consistently ranked as one of the top universities, both nationally and internationally. It?is a world-renowned?institution of higher learning with research activities spanning two campuses, 11 faculties, 13 professional schools, 300 programs of study and over 40,000 students, including more than 10,200 graduate students. McGill attracts students from over 150 countries around the world, its 12,800 international students making up 31% of the student body. Over half of McGill students claim a first language other than English, including approximately 19% of our students who say French is their mother tongue.

https://www.mcgill.ca/newsroom/

A toxin produced by bacteria as a defence mechanism causes mutations in target bacteria that could help them survive, according to a study published today in eLife.

The finding suggests that competitive encounters between bacterial cells could have profound consequences on the evolution of bacterial populations.

When bacterial cells come into contact, they often produce toxins as a defence mechanism. Although it is known that the bacteria producing these toxins have a competitive advantage, exactly how the toxins affect the recipient cells is less clear.

"Undergoing intoxication is not always detrimental for cells - there are scenarios in which encountering a toxin could provide a benefit, such as generating antibiotic ...

To combat climate change, shifting from fossil fuels to clean and sustainable energy sources is imperative. A popular candidate in this regard is hydrogen, an eco-friendly fuel that produces only water when used. However, the efficient methods of hydrogen production are usually not eco-friendly. The eco-friendly alternative of splitting water with sunlight to produce hydrogen is inefficient and suffers from low stability of the photocatalyst (material that facilitates chemical reactions by absorbing light). How does one address the issue of developing a stable and efficient photocatalyst?

In a study recently published in Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, ...

Having a memory of past events enables us to take smarter decisions about the future. Researchers at the Max-Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization (MPI-DS) and the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have now identified how the slime mold Physarum polycephalum saves memories - although it has no nervous system.

The ability to store and recover information gives an organism a clear advantage when searching for food or avoiding harmful environments. Traditionally it has been attributed to organisms that have a nervous system.

A new study authored by Mirna Kramar (MPI-DS) and Prof. Karen Alim (TUM and MPI-DS) challenges this view by uncovering the surprising abilities of a highly dynamic, single-celled organism to store and ...

During ice ages, the global mean sea level falls because large amounts sea water are stored in the form of huge continental glaciers. Until now, mathematical models of the last ice age could not reconcile the height of the sea level and the thickness of the glacier masses: the so-called Missing Ice Problem. With new calculations that take into account crustal, gravitational and rotational perturbation of the solid Earth, an international team of climate researchers has succeeded in resolving the discrepancy, among them Dr. Paolo Stocchi from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ). The study, now published in the ...

During this unique study, a team of researchers led by Professor Jane Ogden from the University of Surrey investigated the impact of actively preparing or watching others prepare food (e.g., on a cooking show) versus distraction away from this focus. Researchers sought to understand how this may affect the amount of food consumed and influence the desire to continue eating.

To investigate this further, eighty female participants were recruited and assigned to one of four groups: active food preparation (preparing a cheese wrap within 10 minutes), video food preparation (watching a video of a researcher preparing a cheese wrap), distraction ...

University of Alberta researchers have found that limiting the amount of fat the body releases into the bloodstream from fat cells during heart failure could help improve outcomes for patients.

In a recent study published in the American Journal of Physiology, Jason Dyck, professor of pediatrics in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry and director of the U of A's Cardiovascular Research Centre, found that mice with heart failure that were treated with a drug blocking the release of fat into the bloodstream from fat cells saw less inflammation in the heart and throughout the body, and had better outcomes than a control group.

"Many people believe that, by definition, heart failure is only ...

New Orleans, LA - An LSU Health New Orleans School of Public Health study reports a positive association between social vulnerability and COVID-19 incidence at the census tract level and recommends that more resources be allocated to socially vulnerable populations to reduce the incidence of COVID-19. The findings are published in Frontiers in Public Health, available END ...

Gay men are more likely than lesbian women to face stigma and avoidant prejudice from their heterosexual peers due to the sound of their voice, a new study in the British Journal of Social Psychology reports. Researchers also found that gay men who believe they sound gay anticipate stigma and are more vigilant regarding the reactions of others.

During this unique study researchers from the University of Surrey investigated the role of essentialist beliefs -- the view that every person has a set of attributes that provide an insight into their identity -- of heterosexual, lesbian ...

In Wonderland, Alice drank a potion to shrink herself. In nature, some animal species shrink to escape the attention of human hunters, a process that takes from decades to millennia. To begin to understand the genetics of shrinking, scientists working at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama successfully extracted DNA from marine shells. Their new technique will not only shed light on how animals from lizards to lemurs shrink, it will reveal many other stories hidden in shells.

"Humans are unique as predators," said Alexis Sullivan, doctoral student at Penn ...

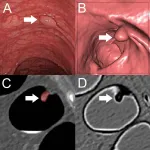

OAK BROOK, Ill. - A machine learning algorithm helps accurately differentiate benign and premalignant colorectal polyps on CT colonography scans, according to a study published in the journal Radiology.

Colorectal cancer is among the three most common causes of cancer-related death among men and women in industrialized countries. Most types of colorectal cancer originate from adenomatous polyps--gland-like growths on the mucous membrane lining the large intestine--that develop over several years. Early detection and removal of these precancerous polyps can reduce the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

During the last two decades, CT colonography emerged as a noninvasive ...