Extreme melt on Antarctica's George VI ice shelf

2021-02-25

(Press-News.org) Antarctica's northern George VI Ice Shelf experienced record melting during the 2019-2020 summer season compared to 31 previous summers of dramatically lower melt, a University of Colorado Boulder-led study found. The extreme melt coincided with record-setting stretches when local surface air temperatures were at or above the freezing point.

"During the 2019-2020 austral summer, we observed the most widespread melt and greatest total number of melt days of any season for the northern George VI Ice Shelf," said CIRES Research Scientist Alison Banwell, lead author of the study published in The Cryosphere.

Banwell and her co-authors--scientists at CU Boulder's National Snow and Ice Data Center and the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, NASA Goddard and international institutions--studied the 2019-2020 melt season on the northern George VI Ice Shelf using a variety of satellite observations that can detect meltwater on top of the ice and within the near-surface snow.

Surface meltwater ponding is potentially dangerous to ice shelves, according to Banwell, because when these lakes drain, the ice fractures and may trigger ice-shelf break-up. "The George VI Ice Shelf buttresses the largest volume of upstream grounded ice of any Antarctic Peninsula ice shelf. So if this ice shelf breaks up, ice that rests on land would flow more quickly into the ocean and contribute more to sea level rise than any other ice shelf on the Peninsula," Banwell said.

The 2019-2020 melt season was the longest for the northern George VI Ice Shelf--the second largest ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula--but it wasn't the longest melt season over the entire peninsula: the 1992-1993 melt season was the longest. But as air temperatures continue to warm, increased melting on the northern George VI Ice Shelf and other Antarctic ice shelves may lead to ice-shelf break-up events and ultimately sea-level rise.

To determine the factors that caused the record melt on the northern George VI Ice Shelf, the researchers examined local weather data--including surface temperature, relative humidity, wind direction, and wind speed--from the British Antarctic Survey's Fossil Bluff weather station on the ice shelf's western margin.

Banwell and her colleagues documented several multi-day periods with warmer-than-average air temperatures that likely contributed to the exceptional melt of 2019-2020. "Overall, a higher percentage of air temperatures during the 2019-2020 season--33 percent--were at or above zero degrees Celsius (32 degrees Fahrenheit) compared to any prior season going back to 2007," Banwell said.

The researchers identified periods from late November onwards when temperatures were consistently above the freezing point for up to 90 hours. "When the temperature is above zero degrees Celsius, that limits refreezing and also leads to further melting. Water absorbs more radiation than snow and ice, and that leads to even more melting," Banwell said.

To detect surface melt over large areas, the researchers used satellite microwave data. "Microwave data lets us look at the brightness temperature of the surface and the near surface snow, which indicates whether or not there is meltwater present," Banwell said. Observations going back to 1979 showed that the extent and duration of surface melt on the northern George VI Ice Shelf in 2019-2020 were greater than the 31 previous summers.

Next, the researchers used satellite imagery to calculate the volume of meltwater on the George VI Ice Shelf, finding that the 2019-2020 melt season had the largest volume of surface meltwater since 2013. Meltwater ponding peaked on January 19, 2020, when satellite images showed 23 percent of the entire study area covered in water, with a total volume of 0.62 km3--equal to about 250,000 Olympic-size swimming pools.

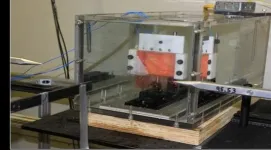

Banwell's research on ice-shelf stability includes a field project funded by the National Science Foundation. During the researchers' first field season in November 2019, they installed instruments to measure changes in the elevation, lake depth and weather conditions on the northern George VI Ice Shelf. "We were due to go back in November 2020, but that was canceled due to COVID," Banwell said. "We hope to return later this year when it's once again safe to pursue field work in this remote region of Earth."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-25

Nanoengineers at the University of California San Diego have discovered new fundamental insights for developing lithium metal batteries that perform well at ultra-low temperatures; mainly, that the weaker the electrolyte holds on to lithium ions, the better. By using such a weakly binding electrolyte, the researchers developed a lithium metal battery that can be repeatedly recharged at temperatures as low as -60 degrees Celsius--a first in the field.

Researchers report their work in a paper published Feb. 25 in Nature Energy.

In tests, the proof-of-concept battery retained 84% and 76% of its capacity over 50 cycles at -40 and -60 degrees Celsius, respectively. Such performance is unprecedented, researchers ...

2021-02-25

The exfoliation of graphite into graphene layers inspired the investigation of thousands of layered materials: amongst them transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs). These semiconductors can be used to make conductive inks to manufacture printed electronic and optoelectronic devices. However, defects in their structure may hinder their performance. Now, Graphene Flagship researchers have overcome these hurdles by introducing 'molecular bridges'- small molecules that interconnect the TMD flakes, thereby boosting the conductivity and overall performance.

The results, published in Nature Nanotechnology, come from a multidisciplinary collaboration between Graphene Flagship partners the University of Strasbourg and CNRS, France, AMBER and Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, ...

2021-02-25

Human rights law can provide a transparent and fair framework for vaccine allocations, researchers suggest.

- All countries face the ethical challenge of how to allocate limited supplies of safe, effective COVID-19 vaccines

- Researchers say that governments should look to human rights principles and commitments to help them decide who should get priority for the first available doses of COVID-19 vaccine.

- A human rights approach would include social vulnerability alongside medical vulnerability in decision-making because health is affected by social factors.

- National vaccine roll-outs should take account of these overlapping vulnerabilities

As Governments around the world wrestle with the question of designing ...

2021-02-25

Future fully autonomous vehicles will rely on sensors to operate, one type of these sensors is LiDAR

LiDAR sensor's effectiveness in detecting objects at a distance in heavy rain decreases, researchers from WMG, University of Warwick have found

Researchers used the WMG 3xD simulator to test the sensor detection of objects in rain, simulating real world roads and weather

High level autonomous vehicles (AVs) are promised by Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and technology companies to improve road safety as well as bringing economical and societal benefits to us all.

All high-level AVs rely heavily on sensors, and in the paper, 'Realistic LiDAR with Noise Model for Real-Tim Testing of Automated Vehicles in ...

2021-02-25

PITTSBURGH--Babies whose births were depicted in Bollywood films from the 1950s and 60s were more often than not boys; in today's films, boy and girl newborns are about evenly split. In the 50s and 60s, dowries were socially acceptable; today, not so much. And Bollywood's conception of beauty has remained consistent through the years: beautiful women have fair skin.

Fans and critics of Bollywood -- the popular name for a $2.1 billion film industry centered in Mumbai, India -- might have some inkling of all this, particularly as movies often reflect changes in the culture. But these insights came via an automated computer analysis designed by Carnegie Mellon University computer ...

2021-02-25

Sea turtles are witnesses and victims of the high level of plastic pollution of the Adriatic Sea. A group of researchers at the University of Bologna analysed 45 turtles hospitalised at Fondazione Cetacea in Riccione and found plastic debris in their faeces. Besides confirming the role of turtles as ideal sentinels to monitor plastic pollution in the sea, the results of their analysis - published in the journal Frontiers of Marine Medicine - crucially show how the plastic debris in their intestines can dangerously alter their microbiota, eventually compromising their health.

"The results ...

2021-02-25

RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. -- Research shows that Soldiers exposed to shockwaves from military explosives are at a higher risk for developing Alzheimer's disease -- even those that don't have traumatic brain injuries from those blasts. A new Army-funded study identifies how those blasts affect the brain.

Researchers at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke in collaboration with the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, now known as DEVCOM, the Army Research Laboratory, and the National Institutes of Health found that the mystery behind blast-induced neurological ...

2021-02-25

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- The optimal timeframe for donating convalescent plasma for use in COVID-19 immunotherapy, which was given emergency use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration in August 2020, is within 60 days of the onset of symptoms, according to a new Penn State-led study. The research also reveals that the ideal convalescent plasma donor is a recovered COVID-19 patient who is older than 30 and whose illness had been severe.

"Millions of individuals worldwide have recovered from COVID-19 and may be eligible for participation in convalescent plasma donor programs," said Vivek Kapur, professor of microbiology and infectious diseases, Penn State. "Our findings enable identification ...

2021-02-25

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. --Many climate models focus on scenarios decades into the future, making their outcomes seem unreliable and problematic for decision-making in the immediate future. In a proactive move, researchers are using short-term forecasts to stress the urgency of drought risk in the United States and inform policymakers' actions now.

A new study led by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign civil and environmental engineering professor Ximing Cai examines how drought propagates through climate, hydrological, ecological and social systems throughout different U.S. regions. The results are published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

"The same amount of precipitation, or the lack of thereof, in one region could have very different impacts on the hydrologic ...

2021-02-25

Black men and women, as well as adolescent boys and girls, may react differently to perceived racial discrimination, with Black women and girls engaging in more exercise and better eating habits than Black men and boys when faced with discrimination, according to research published by the American Psychological Association.

"In this study, Black women and girls didn't just survive in the face of racism, they actually responded in a positive manner, in terms of their health behavior," said lead researcher Frederick Gibbons, PhD, with the University of Connecticut. "This gives us some hope that despite the spike in racism across the country, some people are finding healthy ways to cope." ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Extreme melt on Antarctica's George VI ice shelf