Study identifies potential link between Soldiers exposed to blasts, Alzheimer's

2021-02-25

(Press-News.org) RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. -- Research shows that Soldiers exposed to shockwaves from military explosives are at a higher risk for developing Alzheimer's disease -- even those that don't have traumatic brain injuries from those blasts. A new Army-funded study identifies how those blasts affect the brain.

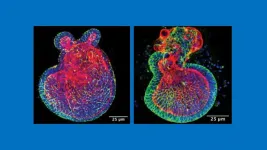

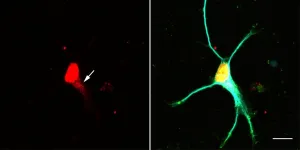

Researchers at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke in collaboration with the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, now known as DEVCOM, the Army Research Laboratory, and the National Institutes of Health found that the mystery behind blast-induced neurological complications when traumatic damage is undetected may be rooted in distinct alterations to the tiny connections between neurons in the hippocampus, the part of the brain particularly involved in memory encoding and social behavior.

The research published in Brain Pathology, the medical journal of the International Society of Neuropathology, was funded by the lab's Army Research Office.

"Blasts can lead to debilitating neurological and psychological damage but the underlying injury mechanisms are not well understood," said Dr. Frederick Gregory, program manager, ARO. "Understanding the molecular pathophysiology of blast-induced brain injury and potential impacts on long-term brain health is extremely important to understand in order to protect the lifelong health and well-being of our service members."

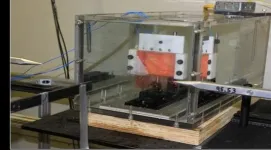

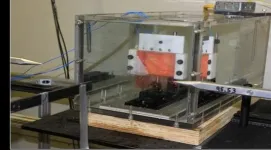

The research team tested slices of rat hippocampus by exposing the healthy tissue to controlled military blast waves. In the experimental brain explants (tissue slices maintained alive in culture dishes), the rapid blast waves produced by the detonated military explosives led to selective reductions in components of brain connections needed for memory, and the distinct electrical activity from those neuronal connections was sharply diminished.

The research showed that the blast-induced effects were evident among healthy neurons with subtle synaptic pathology, which may be an early indicator of Alzheimer's-type pathogenesis occurring independent of overt brain damage.

"This finding may explain those many blast-exposed individuals returning from war zones with no detectable brain injury, but who still suffer from persistent neurological symptoms, including depression, headaches, irritability and memory problems," said Dr. Ben Bahr, the William C. Friday distinguished professor of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry at UNC-Pembroke.

The researchers believe that the increased risk of developing Alzheimer's disease is likely rooted in the disruption of neuronal communication instigated by blast exposures.

"Early detection of this measurable deterioration could improve diagnoses and treatment of recurring neuropsychiatric impediments, and reduce the risk of developing dementia and Alzheimer's disease later in life," Bahr said.

INFORMATION:

UNC-Pembroke is a minority-serving institution.

DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory is an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command. As the Army's corporate research laboratory, ARL is operationalizing science to achieve transformational overmatch. Through collaboration across the command's core technical competencies, DEVCOM leads in the discovery, development and delivery of the technology-based capabilities required to make Soldiers more successful at winning the nation's wars and come home safely. DEVCOM is a major subordinate command of the Army Futures Command.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-25

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- The optimal timeframe for donating convalescent plasma for use in COVID-19 immunotherapy, which was given emergency use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration in August 2020, is within 60 days of the onset of symptoms, according to a new Penn State-led study. The research also reveals that the ideal convalescent plasma donor is a recovered COVID-19 patient who is older than 30 and whose illness had been severe.

"Millions of individuals worldwide have recovered from COVID-19 and may be eligible for participation in convalescent plasma donor programs," said Vivek Kapur, professor of microbiology and infectious diseases, Penn State. "Our findings enable identification ...

2021-02-25

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. --Many climate models focus on scenarios decades into the future, making their outcomes seem unreliable and problematic for decision-making in the immediate future. In a proactive move, researchers are using short-term forecasts to stress the urgency of drought risk in the United States and inform policymakers' actions now.

A new study led by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign civil and environmental engineering professor Ximing Cai examines how drought propagates through climate, hydrological, ecological and social systems throughout different U.S. regions. The results are published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

"The same amount of precipitation, or the lack of thereof, in one region could have very different impacts on the hydrologic ...

2021-02-25

Black men and women, as well as adolescent boys and girls, may react differently to perceived racial discrimination, with Black women and girls engaging in more exercise and better eating habits than Black men and boys when faced with discrimination, according to research published by the American Psychological Association.

"In this study, Black women and girls didn't just survive in the face of racism, they actually responded in a positive manner, in terms of their health behavior," said lead researcher Frederick Gibbons, PhD, with the University of Connecticut. "This gives us some hope that despite the spike in racism across the country, some people are finding healthy ways to cope." ...

2021-02-25

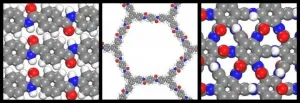

ADELPHI, Md. -- Army researchers reached a breakthrough in the nascent science of two-dimensional polymers thanks to a collaborative program that enlists the help of lead scientists and engineers across academia known as joint faculty appointments.

Researchers from the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, now known as DEVCOM, Army Research Laboratory partnered with Prof. Steve Lustig, a joint faculty appointment at Northeastern University, to accelerate the development of 2D polymers for military applications.

The collaboration with ARL Northeast led to a groundbreaking study published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Macromolecules. Editors featured the research in a cover article.

"2D polymers have been studied very seriously from a synthetic ...

2021-02-25

Researchers have developed a tool to identify security and privacy risks associated with Covid-19 contact tracing apps.

COVIDGuardian, the first automated security and privacy assessment tool, tests contact tracing apps for potential threats such as malware, embedded trackers and private information leakage.

Using the COVIDGuardian tool, cybersecurity experts assessed 40 Covid-19 contact tracing apps that have been employed worldwide for potential privacy and security threats. Their findings include that:

72.5 per cent of the apps use at least one insecure cryptographic ...

2021-02-25

Medical researchers have long understood that a pregnant mother's diet has a profound impact on her developing fetus's immune system and that babies -- especially those born prematurely -- who are fed breast milk have a more robust ability to fight disease, suggesting that even after childbirth, a mother's diet matters. However, the biological mechanisms underlying these connections have remained unclear.

Now, in a study published Feb. 15, 2021, in the journal Nature Communications, a Johns Hopkins Medicine research team reports that pregnant mice fed a diet rich in a molecule found abundantly in cruciferous vegetables -- such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts and cauliflower -- gave birth to pups with stronger protection against necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). ...

2021-02-25

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as various forms of senile dementia or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), have one thing in common: large amounts of certain RNA-protein complexes (snRNPs) are produced and deposited in the nerve cells of those affected - and this hinders the function of the cells. The overproduction is possibly caused by a malfunction in the assembly of the protein complexes.

How the production of these protein complexes is regulated was unknown until now. Researchers from Martinsried and Würzburg in Bavaria, Germany, have solved the puzzle and now report on it in the open access journal Nature Communications. They describe in detail a signaling pathway that prevents the overproduction of snRNPs when they are not needed. The results should ...

2021-02-25

A diet rich in human food may be wreaking havoc on the health of urban coyotes, according to a new study by University of Alberta biologists.

The research team from the Faculty of Science examined the stomach contents, gut microbiome and overall health of nearly 100 coyotes in Edmonton's capital region. Their results also show coyotes that consume more human food have more human-like gut bacteria--with potential impact on their nutrition, immune function and, based on similar findings in dogs, even behaviour.

"If eating human food disturbs the 'natural' coyote gut bacteria, it is possible that eating human food has the potential to affect all ...

2021-02-25

The answer to the age-old mystery of the evolutionary origins of vertebrate eyes may lie in hagfish, according to a new study by biologists at the University of Alberta.

"Hagfish eyes can help us understand the origins of human vision by expanding our understanding of the early steps in vertebrate eye evolution," explained lead author Emily Dong, who conducted the research during her graduate studies with Ted Allison, a professor in the Faculty of Science and member of the U of A's Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute. "Our findings solidify the hagfish's place among vertebrates and open the door to further research to uncover the finer details ...

2021-02-25

Blocking seizures after a head injury could slow or prevent the onset of dementia, according to new research by University of Alberta biologists.

"Traumatic brain injury is a major risk factor for dementia, but the reason this is the case has remained mysterious," said Ted Allison, co-author and professor in the Department of Biological Sciences in the Faculty of Science. "Through this research, we have discovered one important way they are linked--namely, post-injury seizures."

"There is currently no treatment for the long-term effects of traumatic brain injury, which includes developing dementia," added lead author Hadeel Alyenbaawi, who recently completed her PhD dissertation on this topic in the Department of Medical Genetics in the Faculty ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Study identifies potential link between Soldiers exposed to blasts, Alzheimer's