(Press-News.org) Scientists have taken a significant step forward in their search for the origin of a progressive eye condition which causes sight loss and can lead to corneal transplant.

A new study into keratoconus by an international team of researchers, including a University of Leeds group led by Chris Inglehearn, Professor of Molecular Ophthalmology in the School of Medicine, has for the first time detected DNA variations which could provide clues as to how the disease develops.

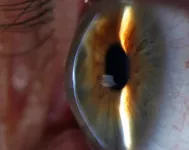

Keratoconus causes the cornea, which is?the clear outer layer?at the front of the eye, to thin and bulge outwards into a cone shape over time, resulting in blurred vision and sometimes blindness. It usually emerges in young adulthood, often with lifelong consequences, and affects 1 in 375 people on average, though in some populations this figure is much higher.

It is more common in people with an affected relative, leading scientists to believe there could be a genetic link.

Glasses or contact lenses can be used to correct vision in the early stages. The only treatment is 'cornea cross-linking', a procedure where targeted UV light is used to strengthen the corneal tissue. In very advanced cases a corneal transplant may be needed.

Professor Inglehearn said: "This multinational, multicenter study gives us the first real insights into the cause of this potentially blinding condition and opens the way for genetic testing in individuals at risk."

The team, led by Alison Hardcastle, Professor of Molecular Genetics at UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, and Dr Pirro Hysi at King's College London, and including researchers from the UK, US, Czech Republic, Australia, the Netherlands, Austria and Singapore, compared the full genetic code of 4,669 people with keratoconus to that of 116,547 people without the condition.

The team pinpointed short sequences of DNA that were significantly altered in genomes of people with keratoconus, offering clues about how it develops.

The findings indicate that people with keratoconus tend to have faulty collagen networks in their corneas, and that there may be abnormalities in the cells' programming which affect their development. These promising insights were not possible in previous studies due to insufficient sample sizes.

Future work will now aim to understand the precise effects of these DNA variations on corneal biology and pinpoint the mechanism by which keratoconus then develops. It will also be crucial to identify any remaining genetic variations among keratoconus patients that were not picked up in this study.

The work has brought science a step closer to earlier diagnosis and potentially even new therapeutic targets, offering hope to current and future keratoconus patients.

The study, A multi-ethnic genome-wide association study implicates collagen matrix integrity and cell differentiation pathways in keratoconus, was funded by Moorfields Eye Charity, and is published in Communications Biology today.

Dr Hysi said: "The results of this work will enable us to diagnose keratoconus even before it manifests; this is great news because early intervention can avoid blinding consequences."

Professor Hardcastle said: "This study represents a substantial advance of our understanding of keratoconus. We can now use this new knowledge as the basis for developing a genetic test to identify individuals at risk of keratoconus, at a stage when vision can be preserved, and in the future develop more effective treatments."

Professor Stephen Tuft, from Moorfields Eye Hospital, said: "If we can find ways to identify keratoconus early, corneal collagen cross linking can prevent progression of the disease in the great majority of cases.

"We would like to thank the thousands of individuals who attend our Moorfields Eye Hospital cornea clinic and donated a DNA sample, without whom this important study would not have been possible."

INFORMATION:

Further information

Picture: The cornea of a keratoconus sufferer. Credit: Community Eye Health via Flickr

For media enquiries contact University of Leeds press officer Lauren Ballinger via l.ballinger@leeds.ac.uk

University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is one of the largest higher education institutions in the UK, with more than 38,000 students from more than 150 different countries, and a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive universities. The University plays a significant role in the Turing, Rosalind Franklin and Royce Institutes.

We are a top ten university for research and impact power in the UK, according to the 2014 Research Excellence Framework, and are in the top 100 of the QS World University Rankings 2021.

The University was awarded a Gold rating by the Government's Teaching Excellence Framework in 2017, recognising its 'consistently outstanding' teaching and learning provision. Twenty-six of our academics have been awarded National Teaching Fellowships - more than any other institution in England, Northern Ireland and Wales - reflecting the excellence of our teaching.

http://www.leeds.ac.uk

Follow University of Leeds or tag us in to coverage: Twitter Facebook LinkedIn Instagram

Researchers are in the search for generalisable rules and patterns in nature. Biogeographer Julia Kemppinen together with her colleagues tested if plant functional traits show similar patterns along microclimatic gradients across far-apart regions from the high-Arctic Svalbard to the sub-Antarctic Marion Island. Kemppinen and her colleagues found surprisingly identical patterns.

It is widely known that global vegetation patterns and plant properties follow major differences in climate. Yet, it has remained a mystery how well the same rules can be applied at very local scales. Are responses to the environment similar in plant communities ...

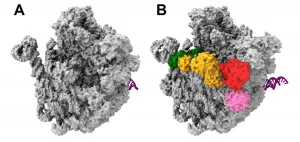

Ribosome formation is viewed as a promising potential target for new antibacterial agents. Researchers from Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin have gained new insights into this multifaceted process. The formation of ribosomal components involves multiple helper proteins which, much like instruments in an orchestra, interact in a coordinated way. One of these helper proteins - protein ObgE - acts as the conductor, guiding the entire process. The research, which produced the first-ever image-based reconstruction of this process, has been published in Molecular Cell*.

Ribosomes are an essential component of all living cells. Frequently referred to as 'molecular protein factories', they translate genetic information into chains of linked-up ...

What can you see on this picture (next to thearticle)? Say what comes to your mind immediately!

If you said „star", you focus rather on the details, if you said „sun", then rather on the global pattern.

People can be different in whether they typically see the forest or the trees, but the dominant attentional mode is focusing first on the whole, and then on the details. This is the same with children. Or so it has been until now! Children of the Alpha Generation (who has been born after 2010) typically grow up with mobile devices in their hands which seems to change how they perceive the world, as Hungarian researchers showed.

The Alpha Generation Lab of Diagnostics and Therapy Excellence Programme at Eötvös Loránd University (Budapest) studies ...

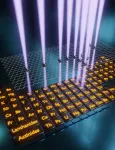

Materials - Quantum building blocks

Oak Ridge National Laboratory scientists demonstrated that an electron microscope can be used to selectively remove carbon atoms from graphene's atomically thin lattice and stitch transition-metal dopant atoms in their place.

This method could open the door to making quantum building blocks that can interact to produce exotic electronic, magnetic and topological properties.

This is the first precision positioning of transition-metal dopants in graphene. The produced graphene-dopant complexes can exhibit atomic-like behavior, inducing desired properties in the graphene.

"What could ...

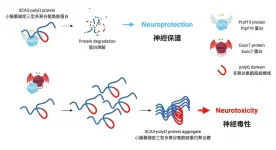

Collaborating with the University of Oxford, Professor Ho Yin Edwin Chan's research team from the School of Life Sciences of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) recently unveiled the counteracting relationship between pre-mRNA-processing factor 19 (Prpf19) and exocyst complex component 7 (Exoc7) in controlling the degradation of disease protein and neurodegeneration of the rare hereditary ataxia. The research findings have been published in the prestigious scientific journal, Cell Death & Disease.

Protein misfolding contributes to the pathogenesis of SCA3

Proteins play a significant role in every single cell development in the human body, including neurons. Numerous studies have proved that misfolds and aggregation of ...

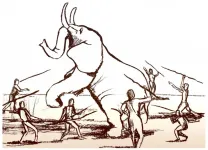

A new paper by Dr. Miki Ben-Dor and Prof. Ran Barkai from the Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University proposes an original unifying explanation for the physiological, behavioral and cultural evolution of the human species, from its first appearance about two million years ago, to the agricultural revolution (around 10,000 BCE). According to the paper, humans developed as hunters of large animals, causing their ultimate extinction. As they adapted to hunting small, swift prey animals, humans developed higher cognitive abilities, evidenced by the most obvious evolutionary change - the growth of brain volume from ...

A study carried out by researchers from the Institute of Genomics, University of Tartu revealed that human gut microbiome can be used to predict changes in Type 2 diabetes related glucose regulation up to four years ahead.

Type 2 diabetes is a metabolic disease characterized by elevated blood glucose levels that contributes to millions of deaths worldwide each year and its prevalence is rapidly increasing. Type 2 diabetes is preceded by "prediabetes" - a condition when the glucose levels have started to rise, but the progression of the disease ...

Takeaway coffees - they're a convenient start for millions of people each day, but while the caffeine perks us up, the disposable cups drag us down, with nearly 300 billion ending up in landfill each year.

While most coffee drinkers are happy to make a switch to sustainable practices, new research from the University of South Australia shows that an absence of infrastructure and a general 'throwaway' culture is severely delaying sustainable change.

It's a timely finding, particularly given the new bans on single-use plastics coming into effect in South Australia today, and the likelihood of takeaway coffee cups taking ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Single-celled algae and animal sperm cells are widely separated in evolution but both swim in the same way, by waving their protruding hairs, called cilia or flagella. Motion is driven by molecular motors, complex assemblies of proteins that exert a force when changing shape. The motor proteins are connected to the cell's internal skeleton of microtubules; the moving force from the motor causes microtubules to slide, moving the flagella and propelling the cell.

Now a team led by Professor Kazuo Inaba of the University of Tsukuba in collaboration with scientists from Osaka University, Tokyo Institute of Technology and Paul Scherrer Institute has described a new protein that is closely ...

While many people believe misinformation on Facebook and Twitter from time to time, people with lower education or health literacy levels, a tendency to use alternative medicine or a distrust of the health care system are more likely to believe inaccurate medical postings than others, according to research published by the American Psychological Association.

"Inaccurate information is a barrier to good health care because it can discourage people from taking preventive measures to head off illness and make them hesitant to seek care when they get sick," said lead author Laura D. Scherer, PhD, with the University of Colorado School of Medicine. "Identifying who is most susceptible to misinformation ...