How does your brain process emotions? Answer could help address loneliness epidemic

Study finds specific brain regions respond opposingly to emotions related to loneliness and wisdom

2021-03-05

(Press-News.org) Research over the last decade has shown that loneliness is an important determinant of health. It is associated with considerable physical and mental health risks and increased mortality. Previous studies have also shown that wisdom could serve as a protective factor against loneliness. This inverse relationship between loneliness and wisdom may be based in different brain processes.

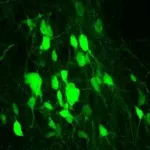

In a study published in the March 5, 2021 online edition of Cerebral Cortex, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine found that specific regions of the brain respond to emotional stimuli related to loneliness and wisdom in opposing ways.

"We were interested in how loneliness and wisdom relate to emotional biases, meaning how we respond to different positive and negative emotions," said Jyoti Mishra, PhD, senior author of the study, director of the NEATLabs and assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

The study involved 147 participants, ages 18 to 85. The subjects performed a simple cognitive task of determining which direction an arrow was pointed while faces with different emotions were presented in the background.

"We found that when faces emoting anger were presented as distractors, they significantly slowed simple cognitive responses in lonelier individuals. This meant that lonelier individuals paid more attention to threatening stimuli, such as the angry faces."

"For wisdom, on the other hand, we found a significant positive relationship for response speeds when faces with happy emotions were shown, specifically individuals who displayed wiser traits, such as empathy, had speedier responses in the presence of happy stimuli."

Electroencephalogram (EEG)-based brain recordings showed that the part of the brain called the temporal-parietal junction (TPJ) was activating differently in lonelier versus wiser individuals. TPJ is important for processing theory of mind, or the degree of capacity for empathy and understanding of others. The study found it more active in the presence of angry emotions for lonelier people and more active in the presence of happy emotions for wiser people.

Researchers also noted greater activity to threatening stimuli for lonelier individuals in the left superior parietal cortex, the brain region important for allocating attention, while wisdom was significantly related to enhanced happy emotion-driven activity in the left insula of the brain, responsible for social characteristics like empathy.

"This study shows that the inverse relationship between loneliness and wisdom that we found in our previous clinical studies is at least partly embedded in neurobiology and is not merely a result of subjective biases," said study author Dilip V. Jeste, MD, senior associate dean for the Center of Healthy Aging and Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry and Neurosciences at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

"These findings are relevant to the mental and physical health of individuals because they give us an objective neurobiological handle on how lonelier or wiser people process information," said Mishra. "Having biological markers that we can measure in the brain can help us develop effective treatments. Perhaps we can help answer the question, 'Can you make a person wiser or less lonely?' The answer could help mitigate the risk of loneliness."

The authors say next steps include a longitudinal study and an intervention study.

"Ultimately, we think these evidence-based cognitive brain markers are the key to developing better health care for the future that may address the loneliness epidemic," said Mishra.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors include: Gillian Grennan, Pragathi Priyadharsini Balasubramani, Fahad Alim, Mariam Zafar-Khan, UC San Diego; and Ellen Lee, Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-05

DURHAM, N.C. -- When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency.

That's the take-home of a new study that, for the first time, measures precisely how much water humans lose and replace each day compared with our closest living animal relatives.

Our bodies are constantly losing water: when we sweat, go to the bathroom, even when we breathe. That water needs to be replenished to keep blood volume and other body fluids within normal ranges.

And yet, research published March 5 in the journal Current Biology shows that the human body uses 30% to 50% less water per ...

2021-03-05

The idea of creating selectively porous materials has captured the attention of chemists for decades. Now, new research from Northwestern University shows that fungi may have been doing exactly this for millions of years.

When Nathan Gianneschi's lab set out to synthesize melanin that would mimic that which was formed by certain fungi known to inhabit unusual, hostile environments including spaceships, dishwashers and even Chernobyl, they did not initially expect the materials would prove highly porous-- a property that enables the material to store and capture molecules.

Melanin has been found across living organisms, on our skin and the backs of ...

2021-03-05

Using genetic engineering, researchers at UT Southwestern and Indiana University have reprogrammed scar-forming cells in mouse spinal cords to create new nerve cells, spurring recovery after spinal cord injury. The findings, published online today in Cell Stem Cell, could offer hope for the hundreds of thousands of people worldwide who suffer a spinal cord injury each year.

Cells in some body tissues proliferate after injury, replacing dead or damaged cells as part of healing. However, explains study leader END ...

2021-03-05

What The Study Did: The objectives of this study were to examine the characteristics and outcomes among adults hospitalized with COVID-19 at U.S. medical centers and analyze changes in mortality over the initial six months of the pandemic.

Authors: Ninh T. Nguyen, M.D., of the University of California, Irvine Medical Center, in Orange, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0417)

Editor's Note: The article includes ...

2021-03-05

What The Study Did: Survey data were used to estimate changes in racial/ethnic disparities in rates of autism spectrum disorder among U.S. children and adolescents from 2014 through 2019.

Authors: Z. Kevin Lu, Ph.D., of the University of South Carolina in Columbia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0771)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news release.

Embed ...

2021-03-05

What The Study Did: Researchers examined the association of increased anti-immigrant rhetoric during the 2016 presidential campaign with changes in the use of health care services among undocumented patients.

Authors: Joseph Nwadiuko, M.D., M.P.H., M.S.H.P., of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0763)

Editor's Note: Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article ...

2021-03-05

What The Study Did: In this study, many children and adolescents hospitalized for COVID-19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children had neurologic involvement, mostly transient symptoms. A range of life-threatening and fatal neurologic conditions associated with COVID-19 infrequently occurred. Effects on long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes are unknown.

Authors: Adrienne G. Randolph, M.D., of Boston Children's Hospital, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0504)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest ...

2021-03-05

DNA sequencing of bacteria found in pigs and humans in rural eastern North Carolina, an area with concentrated industrial-scale pig-farming, suggests that multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains are spreading between pigs, farmworkers, their families and community residents, and represents an emerging public health threat, according to a study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

S. aureus is commonly found in soil and water, as well as on the skin and in the upper respiratory tract in pigs, other animals, and people. It can cause medical problems from minor skin infections to serious surgical wound infections, pneumonia, and the often-lethal blood-infection condition known as sepsis. The findings provide evidence that multidrug-resistant ...

2021-03-05

Researchers from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, have collaborated on two studies examining the socioeconomic factors involved in the spread of COVID-19.

Professor Alex Bentley and postdoctoral fellow Damian Ruck, both from the Department of Anthropology, joined Josh Borycz, a librarian at Vanderbilt University, to conduct the studies.

"One of our studies considers the global scale of nations and the other uses the national scale for US counties to analyze results during 2020," explained Bentley.

The studies show that the numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths are significantly affected ...

2021-03-05

Two thirds of children use more than one screen at the same time after school, in the evenings and at weekends as part of increasingly sedentary lifestyles, according to new research at the University of Leicester.

An NIHR study of more than 800 adolescent girls between the ages of 11 and 14 identified worrying trends between screen use and lower physical activity - including higher BMI - as well as less sleep.

The use of concurrent screens (termed 'screen stacking') grew over the course of the week - with 59% of adolescents using two or more screens after school, 65% in the evenings, and 68% at weekends.

Some teens reporting using as many as four screens at one time.

But further analysis showed the use of any screen was still detrimental to the indicators ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How does your brain process emotions? Answer could help address loneliness epidemic

Study finds specific brain regions respond opposingly to emotions related to loneliness and wisdom