INFORMATION:

In addition to Subramaniam, the authors of the paper, "Mutant Huntingtin Stalls Ribosomes and Represses Protein Synthesis in a Cellular Model of Huntington Disease," include Mehdi Eshraghi, Pabalu Karunadharma, Neelam Shahani, Nicole Galli, Manish Sharma, Uri Nimrod Ramírez-Jarquín, Katie Florescu, and Jennifer Hernandez of Scripps Research; Juliana Blin and Emiliano P Ricci of the RNA Metabolism in Immunity and Infection Lab, Laboratory of Biology and Cellular Modelling of Lyon, France; Audrey Michel of RiboMaps of Cork, Ireland; and Nicolai Urban of the Max Planck Neuroscience Institute in Jupiter, Florida.

Huntington's disease driven by slowed protein-building machinery in cells

New study shows that mutant huntingtin protein slows ribosomes

2021-03-05

(Press-News.org) JUPITER, FL -- In 1993, scientists discovered that a single mutated gene, HTT, caused Huntington's disease, raising high hopes for a quick cure. Yet today, there's still no approved treatment.

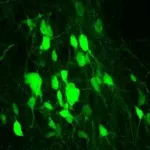

One difficulty has been a limited understanding of how the mutant huntingtin protein sets off brain cell death, says neuroscientist Srinivasa Subramaniam, PhD, of Scripps Research, Florida. In a new study published in Nature Communications on Friday, Subramaniam's group has shown that the mutated huntingtin protein slows brain cells' protein-building machines, called ribosomes.

"The ribosome has to keep moving along to build the proteins, but in Huntington's disease, the ribosome is slowed," Subramaniam says. "The difference may be two, three, four-fold slower. That makes all the difference."

Cells contain millions of ribosomes each, all whirring along and using genetic information to assemble amino acids and make proteins. Impairment of their activity is ultimately devastating for the cell, Subramaniam says.

"It's not possible for the cell to stay alive without protein production," he says.

The team's discoveries were made possible by recent advancements in gene translation tracking technologies, Subramaniam says. The results suggest a new route for development of therapeutics, and have implications for multiple neurodegenerative diseases in which ribosome stalling appears to play a role.

Huntington's disease affects about 10 people per 100,000 in the United States. It is caused by an excessive number of genetic repeats of three DNA building blocks. Known by the letters CAG, short for cytosine, adenine and guanine, 40 or more of these repeats in the HTT gene causes the brain degenerative disease, which is ultimately fatal. The more repeats present, the earlier the onset of symptoms, which include behavioral disturbances, movement and balance difficulty, weakness and difficulty speaking and eating. The symptoms are caused by degeneration of brain tissue that begins in a region called the striatum, and then spreads. The striatum is the region deep in the center of the brain that controls voluntary movement and responds to social reward.

For their experiments, the scientists used striatal cells engineered to have three different degrees of CAG repeats in the HTT gene. They assessed the impact of the CAG repeats using a technology called Ribo-Seq, short for high-resolution global ribosome footprint profiling, plus mRNA-seq, a method that allows a snapshot of which genes are active, and which are not in a given cell at a given moment.

The scientists found that in the Huntington's cells, translation of many, not all, proteins were slowed. To verify the finding, they blocked the cells' ability to make mutant huntingtin protein, and found the speed of ribosome movement and protein synthesis increased. They also assessed how mutant huntingtin protein impacted translation of other genes, and ruled out the possibility that another ribosome-binding protein, Fmrp, might be causing the slowing effect.

Further experiments offered some clues as to how the mutant huntingtin protein interfered with the ribosomes' work. They found it bound directly to ribosomal proteins and the ribosomal assembly, and not only affected speed of protein synthesis, but also of ribosomal density within the cell.

Many questions remain, Subramaniam says, but the advance offers a new direction for helping people with Huntington's disease.

"The idea that the ribosome can stall before a CAG repeat is something people have predicted. We can show that it's there," Subramaniam says. "There's a lot of additional work that needs to be done to figure out how the CAG repeat stalls the ribosome, and then perhaps we can make medications to counteract it."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Canadian scientists and Swiss surgeons discover the cause of excess post-surgical scarring

2021-03-05

The body is amazing at healing itself. However, sometimes it can overdo it. Excess scarring after abdominal and pelvic surgery within the peritoneal cavity can lead to serious complications and sometimes death. The peritoneal cavity has a protective lining containing organs within our abdomen. It also contains fluid to keep the organs lubricated. When the lining gets damaged, tissue and scarring can form, creating problems. Researchers at the University of Calgary and University of Bern, Switzerland, have discovered what's causing the excess scarring and options to try to prevent it.

"This is a worldwide concern. Complications from these peritoneal adhesions cause pain and can lead to life-threatening small bowel obstruction, and infertility in women," says Dr. Joel Zindel, MD, University ...

IU researchers discover new potential for functional recovery after spinal cord injury

2021-03-05

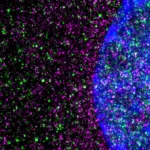

Researchers at Indiana University School of Medicine have successfully reprogrammed a glial cell type in the central nervous system into new neurons to promote recovery after spinal cord injury--revealing an untapped potential to leverage the cell for regenerative medicine.

The group of investigators published their findings March 5 in Cell Stem Cell. This is the first time scientists have reported modifying a NG2 glia--a type of supporting cell in the central nervous system--into functional neurons after spinal cord injury, said Wei Wu, PhD, research associate in neurological surgery at IU School of Medicine and co-first author of the ...

Blind trust in social media cements conspiracy beliefs

2021-03-05

PULLMAN, Wash. - The ability to identify misinformation only benefits people who have some skepticism toward social media, according to a new study from Washington State University.

Researchers found that people with a strong trust in information found on social media sites were more likely to believe conspiracies, which falsely explain significant events as part of a secret evil plot, even if they could identify other types of misinformation. The study, published in the journal Public Understanding of Science on March 5, showed this held true for beliefs in older conspiracy theories as well as newer ones around COVID-19.

"There was some ...

Small volcanic lakes tapping giant underground reservoirs

2021-03-05

Boulder, Colo., USA: In its large caldera, Newberry volcano (Oregon, USA) has two small volcanic lakes, one fed by volcanic geothermal fluids (Paulina Lake) and one by gases (East Lake). These popular fishing grounds are small windows into a large underlying reservoir of hydrothermal fluids, releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) with minor mercury (Hg) and methane into East Lake.

What happens to all that CO2 after it enters the bottom waters of the lake, and how do these volcanic gases influence the lake ecosystem? Some lakes fed by volcanic CO2 have seen catastrophic ...

How does your brain process emotions? Answer could help address loneliness epidemic

2021-03-05

Research over the last decade has shown that loneliness is an important determinant of health. It is associated with considerable physical and mental health risks and increased mortality. Previous studies have also shown that wisdom could serve as a protective factor against loneliness. This inverse relationship between loneliness and wisdom may be based in different brain processes.

In a study published in the March 5, 2021 online edition of Cerebral Cortex, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine found that specific regions of the brain respond to emotional stimuli related to loneliness and wisdom in opposing ways.

"We were interested ...

Humans evolved to be the water-saving ape

2021-03-05

DURHAM, N.C. -- When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency.

That's the take-home of a new study that, for the first time, measures precisely how much water humans lose and replace each day compared with our closest living animal relatives.

Our bodies are constantly losing water: when we sweat, go to the bathroom, even when we breathe. That water needs to be replenished to keep blood volume and other body fluids within normal ranges.

And yet, research published March 5 in the journal Current Biology shows that the human body uses 30% to 50% less water per ...

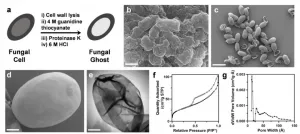

'Fungal ghosts' protect skin, fabric from toxins, radiation

2021-03-05

The idea of creating selectively porous materials has captured the attention of chemists for decades. Now, new research from Northwestern University shows that fungi may have been doing exactly this for millions of years.

When Nathan Gianneschi's lab set out to synthesize melanin that would mimic that which was formed by certain fungi known to inhabit unusual, hostile environments including spaceships, dishwashers and even Chernobyl, they did not initially expect the materials would prove highly porous-- a property that enables the material to store and capture molecules.

Melanin has been found across living organisms, on our skin and the backs of ...

Putting a protein into overdrive to heal spinal cord injuries

2021-03-05

Using genetic engineering, researchers at UT Southwestern and Indiana University have reprogrammed scar-forming cells in mouse spinal cords to create new nerve cells, spurring recovery after spinal cord injury. The findings, published online today in Cell Stem Cell, could offer hope for the hundreds of thousands of people worldwide who suffer a spinal cord injury each year.

Cells in some body tissues proliferate after injury, replacing dead or damaged cells as part of healing. However, explains study leader END ...

Outcomes, mortality among adults hospitalized with COVID-19 at US medical centers

2021-03-05

What The Study Did: The objectives of this study were to examine the characteristics and outcomes among adults hospitalized with COVID-19 at U.S. medical centers and analyze changes in mortality over the initial six months of the pandemic.

Authors: Ninh T. Nguyen, M.D., of the University of California, Irvine Medical Center, in Orange, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0417)

Editor's Note: The article includes ...

Racial/ethnic disparities in autism

2021-03-05

What The Study Did: Survey data were used to estimate changes in racial/ethnic disparities in rates of autism spectrum disorder among U.S. children and adolescents from 2014 through 2019.

Authors: Z. Kevin Lu, Ph.D., of the University of South Carolina in Columbia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0771)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news release.

Embed ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Machine learning reveals Raman signatures of liquid-like ion conduction in solid electrolytes

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia researchers emphasize benefits and risks of generative AI at different stages of childhood development

Why conversation is more like a dance than an exchange of words

With Evo 2, AI can model and design the genetic code for all domains of life

Discovery of why only some early tumors survive could help catch and treat cancer at very earliest stages

Study reveals how gut bacteria and diet can reprogram fat to burn more energy

Mayo Clinic researchers link Parkinson's-related protein to faster Alzheimer's progression in women

Trends in metabolic and bariatric surgery use during the GLP-1 receptor agonist era

Loneliness, anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in the all of us dataset

A decision-support system to personalize antidepressant treatment in major depressive disorder

Thunderstorms don’t just appear out of thin air - scientists' key finding to improve forecasting

Automated CT scan analysis could fast-track clinical assessments

New UNC Charlotte study reveals how just three molecules can launch gene-silencing condensates, organizing the epigenome and controlling stem cell differentiation

Oldest known bony fish fossils uncover early vertebrate evolution

High‑performance all‑solid‑state magnesium-air rechargeable battery enabled by metal-free nanoporous graphene

Improving data science education using interest‑matched examples and hands‑on data exercises

Sparkling water helps keep minds sharp during long esports sessions

Drone LiDAR surveys of abandoned roads reveal long-term debris supply driving debris-flow hazards

UGA Bioinformatics doctoral student selected for AIBS and SURA public policy fellowship

Gut microbiome connected with heart disease precursor

Nitrous oxide, a product of fertilizer use, may harm some soil bacteria

FAU lands $4.5M US Air Force T-1A Jayhawk flight simulator

SimTac: A physics-based simulator for vision-based tactile sensing with biomorphic structures

Preparing students to deal with ‘reality shock’ in the workplace

Researchers develop beating, 3D-printed heart model for surgical practice

Black soldier fly larvae show promise for safe organic waste removal

People with COPD commonly misuse medications

How periodontitis-linked bacteria accelerate osteoporosis-like bone loss through the gut

Understanding how cells take up and use isolated ‘powerhouses’ to restore energy function

Ten-point plan to deliver climate education unveiled by experts

[Press-News.org] Huntington's disease driven by slowed protein-building machinery in cellsNew study shows that mutant huntingtin protein slows ribosomes