Fossil lamprey larvae overturn textbook assumptions on vertebrate origins

Study shows studies of the origin of vertebrates - including human - were based on incorrect assumptions since the late 1800s

2021-03-10

(Press-News.org) The unprecedented discovery of an ancient lamprey growth series, published in the prestigious scientific journal, Nature, is overturning long-held ideas as to what modern lampreys may tell us about the origin of vertebrates (all animals with a backbone such as goldfish, lizards, crows and people).

"Lampreys and modern hagfish are the only jawless fish alive that branched off from the family tree of vertebrates before they got jaws," says Dr Rob Gess from the Albany Museum in Makhanda, who discovered the ancient fossils. "This makes them very interesting for researchers attempting to understand the earliest stages of vertebrate history."

Until now, it was commonly believed that modern lampreys were swimming time capsules that could give unique insights into the biology and genome (DNA) of a truly ancient lineage.

This belief was supported by the discovery, published in Nature in 2006, of an exquisitely preserved lamprey fossil (Priscomyzon) at the 360-million-year-old Waterloo Farm black shales near Makhanda/Grahamstown, South Africa. The discovery was met with excitement worldwide as it was the oldest lamprey ever found, yet it appeared to have been essentially almost identical to modern adult lampreys. Modern lampreys are bizarre fish, eel-like in shape, that feed by latching onto other fish with a sucker around their mouth, securing their grip with circles of teeth and then drinking their victim's blood after rasping a hole with special teeth on their tongue. Therefore, adult lampreys are clearly successful, having arisen before the first four-legged-animals moved onto land and survived, with little change, ever since.

In many ways, modern lampreys indeed provide unique insights into their ancient ancestry. But new evidence shows that this is not the case when it comes to the juvenile larval stage.

Since the 19th century, biologists have treated the larvae/juveniles of modern lampreys as a relic of deep evolutionary ancestry. These blind, filter-feeding, worm-like larvae (ammocoetes) burrow in stream beds and filter water for minute food particles before slowly transforming into free-swimming, eyed, actively feeding adults. Crucially, this strange life history was thought to echo transformations some 500 million years ago, which gave rise to all fish lineages, including the one that ultimately led to humans. Hence, the last invertebrate ancestor of vertebrates is often portrayed as ammocoete-like, and the earliest vertebrate as being lamprey-like. But for this to be a reasonable model, both ammocoetes and lampreys would need to hark back to the dawn of our (vertebrate) history.

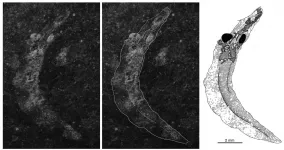

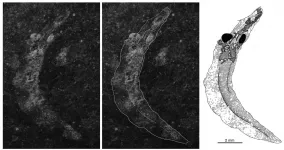

However, the new fossil discoveries contradict the conventional wisdom that our long chain of ancestors ever included a lamprey-larva-like fish. Painstaking excavation of shale samples from Waterloo Farm has revealed a growth series of Priscomyzon illustrating its development from hatchling to adult. Remarkably, the smallest preserved individuals, barely 15mm in length, still carried a yolk sac, signalling that these had only just hatched before entering the fossil record.

Of crucial importance: even the hatchlings were already sighted with large eyes and armed with a toothed sucker, much like the blood-sucking adult phase of modern lampreys, and completely unlike their modern larval counterparts. This drastically different structure of ancient lamprey infants provides evidence that modern lamprey larvae are not evolutionary relics. Instead, the modern filter-feeding phase is a more recent innovation that allowed lampreys to populate and thrive in rivers and lakes. A less complete (previously unpublished) partial growth series of three types of slightly younger lampreys from North America support the finding. Therefore, distant human ancestry seemingly did not include a lamprey-larva-like stage. Modern lampreys now appear to be a highly evolved side branch, which shared a common ancestor with us - probably a jawless fish enclosed in bony armour.

Truly a new entry for the textbooks.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-10

The unpredictable nature of life during the coronavirus pandemic is particularly challenging for many people. Not everyone can cope equally well with the uncertainty and loss of control. Research has shown that while a large segment of the population turns out to be resilient in times of stress and potentially traumatic events, others are less robust and develop stress-related illnesses. Events that some people experience as draining seem to be a source of motivation and creativity for others.

These differing degrees of resilience demonstrate that people recover from stressful events ...

2021-03-10

In a study recently published in Nature Communications, scientists from The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability (DTU) and Yale University have investigated how bacteria that are commonly found in sugarcane ethanol fermentation affect the industrial process. By closely studying the interactions between yeast and bacteria, it is suggested that the industry could improve both its total yield and the cost of the fermentation processes by paying more attention to the diversity of the microbial communities and choosing between good and bad bacteria.

The scientists dissected yeast-bacteria interactions in sugarcane ethanol fermentation by reconstituting every possible combination ...

2021-03-10

Fuel cells, which are attracting attention as an eco-friendly energy source, obtain electricity and heat simultaneously through the reverse reaction of water electrolysis. Therefore, the catalyst that enhances the reaction efficiency is directly connected to the performance of the fuel cell. To this, a POSTECH-UNIST joint research team has taken a step closer to developing high-performance catalysts by uncovering the ex-solution and phase transition phenomena at the atomic level for the first time.

A joint research team of Professor Jeong Woo Han and Ph.D. candidate Kyeounghak Kim of POSTECH's Department of Chemical Engineering, and Professor Guntae Kim of UNIST have uncovered the mechanism by which PBMO - a catalyst used ...

2021-03-10

Italian and Russian researchers confirmed the hypothesis that the self-maintaining order in eukaryotic cells (cells with nuclei) is a result of two spontaneous mechanisms' collaboration. Similar molecules gather into 'drops' on the membrane and then leave it as tiny vesicles enriched by the collected molecules. The paper with the research results was published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

The research was carried out by an international interdisciplinary team of biologists (from Polytechnic University of Turin, Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine of the University of Turin and Candiolo Cancer Institute) and ...

2021-03-10

Variant B.1.1.7 of COVID-19 associated with a significantly higher mortality rate, research shows

The highly infectious variant of COVID-19 discovered in Kent, which swept across the UK last year before spreading worldwide, is between 30 and 100 per cent more deadly than previous strains, new analysis has shown.

A pivotal study, by epidemiologists from the Universities of Exeter and Bristol, has shown that the SARS-CoV-2 variant, B.1.1.7, is associated with a significantly higher mortality rate amongst adults diagnosed in the community compared to previously circulating strains.

The study compared death rates among people infected ...

2021-03-10

Newly published research has revealed a close link between proteins associated with Alzheimer's disease and age-related sight loss. The findings could open the way to new treatments for patients with deteriorating vision and through this study, the scientists believe they could reduce the need for using animals in future research into blinding conditions.

Amyloid beta (AB) proteins are the primary driver of Alzheimer's disease but also begin to collect in the retina as people get older. Donor eyes from patients who suffered from age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the most common cause of blindness amongst adults in the UK, have been shown to contain high levels of AB in their retinas.

This new study, published in the journal Cells, builds on previous ...

2021-03-10

The Telomeres and Telomerase Group led by Maria A. Blasco at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) continues to make progress in unravelling the role that telomeres -the ends of chromosomes that are responsible for cellular ageing as they shorten- play in cancer. The CNIO team was among the first to propose that shelterins, proteins that wrap around telomeres and act as a protective shield, might be therapeutic targets for cancer treatment. Subsequently, they found that eliminating one of these shelterins, TRF1, blocks the initiation and progression of lung cancer and glioblastoma in mouse models and prevents glioblastoma stem cells from forming secondary tumours. Now, in a study published in PLOS Genetics, ...

2021-03-10

People with aphantasia - that is, the inability to visualise mental images - are harder to spook with scary stories, a new UNSW Sydney study shows.

The study, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, tested how aphantasic people reacted to reading distressing scenarios, like being chased by a shark, falling off a cliff, or being in a plane that's about to crash.

The researchers were able to physically measure each participant's fear response by monitoring changing skin conductivity levels - in other words, how much the story made a person sweat. This type of test is commonly ...

2021-03-10

WESTMINSTER, Colorado - March 10, 2021 - The paperbark tree (Melaleuca quinquenervia) was introduced to the U.S. from Australia in the 1900s. Unfortunately, it went on to become a weedy invader that has dominated natural landscapes across southern Florida, including the fragile wetlands of the Everglades.

According to an article in the journal END ...

2021-03-10

ften, humans display biases, i.e., unconscious tendencies towards a type of decision. Despite decades of study, we are yet to discover why biases are so persistent in all types of decisions. "Biases can help us make better decisions when we use them correctly in an action that has previously given us great reward. However, in other cases, biases can play against us, such as when we repeat actions in situations when it would be better not to", says Rubén Moreno Bote, coordinator of the UPF Theoretical and Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory.

In these cases, decisions are guided by tendencies, or inclinations, that do not benefit our wellbeing. For example, playing the lottery more regularly after winning ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Fossil lamprey larvae overturn textbook assumptions on vertebrate origins

Study shows studies of the origin of vertebrates - including human - were based on incorrect assumptions since the late 1800s