How a ladybug warps space-time

Vienna quantum physicists measure the smallest gravitational force yet

2021-03-10

(Press-News.org) Gravity is the weakest of all known forces in nature - and yet it is most strongly present in our everyday lives. Every ball we throw, every coin we drop - all objects are attracted by the Earth's gravity. In a vacuum, all objects near the Earth's surface fall with the same acceleration: their velocity increases by about 9.8 m/s every second. The strength of gravity is determined by the mass of the Earth and the distance from the center. On the Moon, which is about 80 times lighter and almost 4 times smaller than the Earth, all objects fall 6 times slower. And on a planet of the size of a ladybug? Objects would fall 30 billion times slower there than on Earth. Gravitational forces of this magnitude normally occur only in the most distant regions of galaxies to trap remote stars. A team of quantum physicists led by Markus Aspelmeyer and Tobias Westphal of the University of Vienna and the Austrian Academy of Sciences has now demonstrated these forces in the laboratory for the first time. To do so, the researchers drew on a famous experiment conducted by Henry Cavendish at the end of the 18th century.

During the time of Isaac Newton, it was believed that gravity was reserved for astronomical objects such as planets. It was not until the work of Cavendish (and Nevil Maskelyne before him) that it was possible to show that objects on Earth also generate their own gravity. Using an elegant pendulum device, Cavendish succeeded in measuring the gravitational force generated by a lead ball 30 cm tall and weighing 160 kg in 1797. A so-called torsion pendulum - two masses at the ends of a rod suspended from a thin wire and free to rotate - is measurably deflected by the gravitational force of the lead mass. Over the coming centuries, these experiments were further perfected to measure gravitational forces with increasing accuracy.

The Vienna team has picked up this idea and built a miniature version of the Cavendish experiment. A 2 mm gold sphere weighing 90 mg serves as the gravitational mass. The torsion pendulum consists of a glass rod 4 cm long and half a millimeter thick, suspended from a glass fiber a few thousandths of a millimeter in diameter. Gold spheres of similar size are attached to each end of the rod. "We move the gold sphere back and forth, creating a gravitational field that changes over time," explains Jeremias Pfaff, one of the researchers involved in the experiment. "This causes the torsion pendulum to oscillate at that particular excitation frequency." The movement, which is only a few millionths of a millimeter, can then be read out with the help of a laser and allows conclusions to be drawn about the force. The difficulty is keeping other influences on the motion as small as possible. "The largest non-gravitational effect in our experiment comes from seismic vibrations generated by pedestrians and tram traffic around our lab in Vienna," says co-author Hans Hepach: "We therefore obtained the best measurement data at night and during the Christmas holidays, when there was little traffic." Other effects such as electrostatic forces could be reduced to levels well below the gravitational force by a conductive shield between the gold masses.

This made it possible to determine the gravitational field of an object that has roughly the mass of a ladybug for the first time. As a next step, it is planned to investigate the gravity of masses thousands of times lighter.

The possibility of measuring gravitational fields of small masses and at small distances opens up new perspectives for research in gravitational physics; traces of dark matter or dark energy could be found in the behavior of gravity, which could be responsible for the formation of our present universe. Aspelmeyer's researchers are particularly interested in the interface with quantum physics: can the mass be made small enough for quantum effects to play a role? Only time will tell. For now, the fascination with Einstein's theory of gravity still prevails. "According to Einstein, the gravitational force is a consequence of the fact that masses bend spacetime in which other masses move," says first author Tobias Westphal. "So what we are actually measuring here is, how a ladybug warps space-time."

INFORMATION:

Publication in Nature:

Measurement of Gravitational Coupling between Millimeter-Sized Masses

Tobias Westphal, Hans Hepach, Jeremias Pfaff, Markus Aspelmeyer

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03250-7

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-10

A new study published Tuesday 10 March, No Smoking Day, from King's College London highlights the 'clear benefit' of using e-cigarettes daily in order to quit smoking, and supports their effectiveness when compared to other methods of quitting, including nicotine replacement therapy or medication.

Although the number of people in England who smoke has continued to fall in recent years, tobacco smoking is still the leading preventable cause of premature death and disease - killing nearly 75,000 people in England in 2019.

While e-cigarettes have been around for more than a decade, evidence on their effectiveness for helping people to ...

2021-03-10

There's a surprising amount of information stored in the hardened plaque, or calculus, between teeth. And if that calculus belongs to the remains of a person who lived in ancient times, the information could reveal new insights about the past. But the tiny samples can be difficult to work with. Now, in ACS' Journal of Proteome Research, scientists apply a new method to this analysis, finding more proteins than traditional approaches.

The human mouth is full of interesting molecules: DNA and enzymes in saliva, proteins and lipids from bits of food stuck between teeth, the bacterial ...

2021-03-10

Amsterdam, NL, March 10, 2021 - Music-based interventions have become a core ingredient of effective neurorehabilitation in the past 20 years thanks to the growing body of knowledge. In this END ...

2021-03-10

People are different. New technology is good for patients and the healthcare system. But it could also expand the already significant health disparities in Norway and other countries.

"Women and men with higher education in Norway live five to six years longer than people with that only have lower secondary school education," says Emil Øversveen, a postdoctoral fellow at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) Department of Sociology and Political Science.

He is affiliated with CHAIN, the Centre for Global Health Inequalities Research. The centre works to reduce social health ...

2021-03-10

In the dry air and soil of Texas' Southern High Plains, improving soil health can be tough. We usually think of healthy soil as moist and loose with lots of organic matter. But this can be hard to achieve in this arid area of Texas.

Lindsey Slaughter, a member of the Soil Science Society of America, set out with her fellow researchers to test a solution that kills two birds with one stone. They put excess cow manure on these soils to see if they could make them healthier.

The team recently published their research in the Soil Science Society of America Journal.

"We know that planting perennial grasslands for cattle production can help protect and restore soil in semi-arid lands that are likely to erode and degrade from intense ...

2021-03-10

The per-capita rates of new COVID-19 cases and COVID-19 deaths were higher in states with Democrat governors in the first months of the pandemic last year, but became much higher in states with Republican governors by mid-summer and through 2020, possibly reflecting COVID-19 policy differences between GOP- and Democrat-led states, according to a study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Medical University of South Carolina.

For their study, the researchers analyzed data on SARS-CoV-2-positive nasal swab tests, COVID-19 diagnoses, and COVID-19 ...

2021-03-10

Immune cells specialize to ensure the most efficient defense against viruses and other pathogens. Researchers at the University of Basel have shed light on this specialization of T cells and shown that it occurs differently in the context of an acute and a chronic infection. This could be relevant for new approaches against chronic viral infections.

Researchers led by Professor Carolyn King of the University of Basel have developed a method to study the specialization of T cells in the context of infections. In the journal eLife, they report the different directions ...

2021-03-10

The scientists of the National University of Science and Technology "MISIS" (NUST MISIS) being a part of an international team of researches managed to increase the capacity and extend the service life of lithium-ion batteries. According to the researchers, they have synthesized a new nanomaterial that can replace low-efficiency graphite used in lithium-ion batteries today. The results of the research are published in the Journal of Alloys and Compounds.

Lithium-ion batteries are widely used for household appliances from smartphones to electric vehicles. The charge-discharge cycle in such battery is provided by ...

2021-03-10

As plastic debris weathers in aquatic environments, it can shed tiny nanoplastics. Although scientists have a good understanding of how these particles form, they still don't have a good grasp of where all the fragments end up. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Environmental Science & Technology have shown experimentally that most nanoplastics in estuarine waters can clump, forming larger clusters that either settle or stick to solid objects, instead of floating on into the ocean.

There is a huge discrepancy between the millions of tons of plastic waste entering rivers and streams and the amount researchers have found in the oceans. As large pieces of plastic break apart into ...

2021-03-10

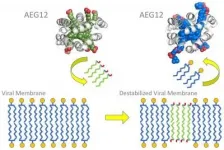

The mosquito protein AEG12 strongly inhibits the family of viruses that cause yellow fever, dengue, West Nile, and Zika and weakly inhibits coronaviruses, according to scientists at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and their collaborators. The researchers found that AEG12 works by destabilizing the viral envelope, breaking its protective covering. Although the protein does not affect viruses that do not have an envelope, such as those that cause pink eye and bladder infections, the findings could lead to therapeutics against viruses that affect millions of people around the world. The research ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How a ladybug warps space-time

Vienna quantum physicists measure the smallest gravitational force yet