(Press-News.org) In previous research, ancient massacre sites found men who died while pitted in battle or discovered executions of targeted families. At other sites, evidence showed killing of members of a migrant community in conflict with previously established communities, and even murders of those who were part of religious rituals.

But a more recent discovery by a research team -- that includes two University of Wyoming faculty members -- reveals the oldest documented site of an indiscriminate mass killing 6,200 years ago in what is now Potocani, Croatia.

"The DNA, combined with the archaeological and skeletal evidence -- especially that indicating systematic violence, perhaps even execution-style -- demonstrates an indiscriminate massacre and haphazard burial of 41 individuals from an early pastoralist community in what is now eastern Croatia," says James Ahern, a UW professor in the Department of Anthropology and associate vice provost for graduate education.

Ahern was a nonsenior co-author of a paper, titled, "Genome-Wide Analysis of Nearly All the Victims of a 6,200-Year-Old Massacre," that was published March 10 in PLOS ONE. The journal accepts research in over 200 subject areas across science, engineering, medicine, and the related social sciences and humanities.

Mario Novak, a research associate with the Institute for Anthropological Research in Zagreb, Croatia, was the paper's lead author. Ivor Jankovic, a UW adjunct professor of anthropology and assistant director of the Institute for Anthropological Research, also was a nonsenior co-author of the study.

Other researchers who contributed to the paper were from the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain; Harvard University; Archaeological Museum in Zagreb, Croatia; University of Zagreb; University of Vienna; Broad Institute of Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Harvard Medical School.

In 2007, the Croatian site underwent a "rescue" excavation that occurred when the burial was uncovered during the construction of a garage on private land, Ahern says. Archaeologists, led by Jacqueline Balen of the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb, working nearby on a cultural resource impact assessment related to the construction of a motorway, were called in to investigate.

In 2012, Ahern and Jankovic, then a research scientist at the Institute for Anthropological Research, were invited by the archaeologists in charge of Potocani discoveries to analyze the skeletal remains. The skeletal remains needed to be cleaned and inventoried, and basic analysis -- such as estimation of age and sex, recording of preserved elements, and basic documentation of pathologies and trauma -- was conducted by Jankovic, Ahern and Zrinka Premuzic, a Ph.D. student at the University of Zagreb.

"This is the oldest known case of indiscriminate, mass killing that we know of," Ahern says. "In some ways, it goes against the conventional wisdom about early agriculturalists -- the Neolithic and Eneolithic -- who have long been thought to have lived in small villages or herding groups.

"The DNA evidence indicates just a few close relatives in such a large sample, meaning that, not only was the violence seemingly indiscriminate, it involved a subset of a much larger local population."

Prior research shows that some early farmers lived in large settlements, such as at Catalhoyuk in Western Asia; and some later Eneolithic peoples, such as those who lived at the Vucedol site in the Balkans. However, Potocani is approximately 1,000 years older than the latter settlement.

The genetic analysis revealed that 70 percent of the analyzed skeletons did not have close kin among the deceased. Additionally, there was no sex bias, as the number of males and females found at the site were almost equal in number. This indicates the massacre was not the outcome of inter-male fighting one would expect in battles, nor was the result of a reprisal event targeting individuals of a specific sex.

Cranial injuries were found on 13 of the 41 individuals massacred at the site, according to the study.

"Although we do not have evidence on the cause of death for the other individuals, their deaths were almost certainly violent," Ahern says. "Multiple radiocarbon dates, as well as the sedimentology of the burial, all indicate a single burial event.

"Furthermore, a majority of violent deaths do not leave clear evidence of trauma in the preserved skeletal remains," he continues. "Individuals could have been strangled, bludgeoned, cut or stabbed in soft-tissue areas or in manners that did not damage underlying bones."

The study also considered the potential role of climate change in the mass burial event. When climate changes, resources such as water, vegetation -- including feed for cattle and other livestock -- and game animals become less predictable. Furthermore, hazards, such as unpredictable extreme weather, become more common.

"These factors tend to disrupt human lifeways, and groups sometimes try to take over others' territories and resources," Ahern explains. "Increases in population size cause groups to overextend their local resources and require expansion into other areas. Both climate change and population increase tend to cause social disruption and violent acts, such as what happened at Potocani, that become more common as groups come into conflict with each other."

Data in the study reveal how organized violence in this period could be indiscriminate, just as indiscriminate killings have been an important feature of life in historic and modern times. The history, development and causes of human violence are crucial to our ability to understand and reduce violence in our own society, Ahern says.

"Perhaps, because of the long history of human violence and warfare and its contemporary relevance, the public is engaged by the sort of narrative about the deep human past that we've been able to recreate through our scientific research," Ahern says. "Furthermore, DNA, heredity and human ancestry are issues that touch everyone's lives. Our research also highlights UW's global engagement and research enterprise."

INFORMATION:

An international research team led by NUST MISIS has developed a new iron-cobalt-nickel nanocomposite with tunable magnetic properties. The nanocomposite could be used to protect money and securities from counterfeiting. The study was published in Nanomaterials.

Presently, research on magnetic nanomaterials with controlled magnetic characteristics is one of the most promising fields. Due to their small size, as well as their excellent magnetic and electric properties these materials have a broad range of potential applications from mobile devices to space technologies.

The new iron-cobalt-nickel nanocomposite was obtained by chemical precipitation, followed by a reduction process.

"This ...

Researchers hope to use an agricultural pest's genetic code against it to prevent billions of dollars in annual losses in the United States.

Stable flies, or Stomoxys calcitrans, are spotted, tan-colored flies found around the world. They are easily mistaken for the common housefly but for one notable distinction: They bite.

"If you get one in your house and it bites you, it's a stable fly," said Joshua Benoit, an assistant professor of biology at the University of Cincinnati.

Stable flies don't bite so much as chomp. They are the scourge of beachgoers in Florida and recreational boaters in upstate New York. According to Thomas Jefferson, they tormented signatories ...

DALLAS - March 10, 2021 - UT Southwestern scientists have identified key genes involved in brain waves that are pivotal for encoding memories. The END ...

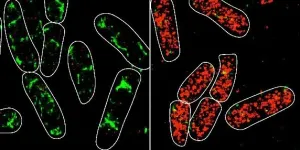

Bacteria employ many different strategies to regulate gene expression in response to fluctuating, often stressful, conditions in their environments. One type of regulation involves non-coding RNA molecules called small RNAs (sRNAs), which are found in all domains of life. A new study led by researchers at the University of Illinois describes, for the first time, the impacts of sRNA interactions in individual bacterial cells. Their findings are reported in the journal Nature Communications, with the paper selected as an Editors' highlight article.

Bacterial sRNAs are often involved in regulating stress responses using mechanisms that involve base-pairing ...

While neurological complications of COVID-19 in children are rare, in contrast to adults, an international expert review of positive neuroimaging findings in children with acute and post-infectious COVID-19 found that the most common abnormalities resembled immune-mediated patterns of disease involving the brain, spine, and nerves. Strokes, which are more commonly reported in adults with COVID-19, were much less frequently encountered in children. The study of 38 children, published in the journal Lancet, was the largest to date of central nervous system imaging manifestations of COVID-19 in children.

"Thanks to a major international collaboration, we found that neuroimaging manifestations ...

When we recall a memory, we retrieve specific details about it: where, when, with whom. But we often also experience a vivid feeling of remembering the event, sometimes almost reliving it. Memory researchers call these processes objective and subjective memory, respectively. A new study from the Center for Mind and Brain at the University of California, Davis, shows that objective and subjective memory can function independently, involve different parts of the brain, and that people base their decisions on subjective memory -- how they feel about a memory -- more than on its accuracy.

"The study distinguishes between ...

Aspirin is an established, safe, and low-cost medication in long-standing common use in prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases, and in the past a pain relief and fever reducing medication. The use of aspirin was very popular during the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic, several decades before in-vitro confirmation of its activity against RNA viruses. Studies showed that aspirin, in addition to its well-known anti-inflammatory effects, could modulate the innate and adaptive immune responses helping the human immune system battle some viral infections.

With this information ...

Computer engineers at the world's largest companies and universities are using machines to scan through tomes of written material. The goal? Teach these machines the gift of language. Do that, some even claim, and computers will be able to mimic the human brain.

But this impressive compute capability comes with real costs, including perpetuating racism and causing significant environmental damage, according to a new paper, "On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? ?" The paper is being presented Wednesday, March 10 at the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency (ACM FAccT).

This is the first exhaustive review of the literature surrounding the risks that come with rapid growth of language-learning technologies, said ...

Effective, specific, with a reversible and non-harmful action: the identikit of the perfect biomaterial seems to correspond to graphene flakes, the subject of a new study carried out by SISSA - International School for Advanced Studies of Trieste, Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (ICN2) of Barcelona and the National Graphene Institute of the University of Manchester, in the framework of the European Graphene Flagship project. This nanomaterial has demonstrated the ability to interact with the functions of the nervous system in vertebrates in a very specific manner, interrupting the building up of a pathological process that leads ...

Healthcare personnel who were infected with COVID-19 had stronger risk factors outside the workplace than in their hospital or healthcare setting. That is the finding of a new study published today in JAMA Network Open conducted by University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers, colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and three other universities.

The study examined survey data from nearly 25,000 healthcare providers in Baltimore, Atlanta, and Chicago including at University of Maryland Medical System (UMMS) hospitals. They found that having a known exposure to someone who tested positive for COVID-19 in the community was the strongest risk factor for testing ...